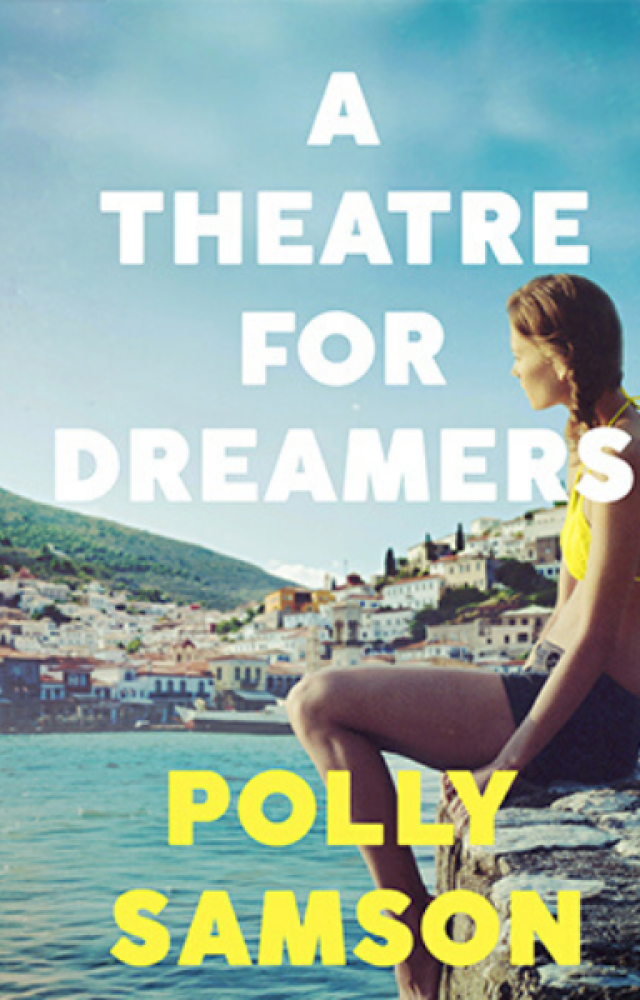

A Theatre for Dreamers

By Polly Sampson

Bloomsbury, 2020, 348 pp., $28.99

Hydra

By Sue Smith

NewSouth Publishing, 2019, 95 pp., $24.99

These two stories — one a novel, the other a play — examine the artists colony that existed on the Greek island of Hydra from the early 1950s to the early '60s. The centre of this creative oasis was the Australian couple Charmian Clift and George Johnston.

Others who passed through for longer or shorter periods were artist Sidney Nolan, actor Peter Finch, singer Leonard Cohen, Marianne Ihlen and a motley collection of would-be writers and artists.

It says a lot about the cultural weight of these people that there has been a recent slew of biographies about them, a documentary film on Ihlen and Cohen, and now these two publications. Their free-spirited example still strikes a chord after all these years.

Johnston was already established as a journalist and writer when he met and fell in love with Clift shortly after World War II. He was famous for his war reporting from China where he had witnessed terrible suffering among refugees fleeing the Japanese. He picked up the tuberculosis that was to kill him in 1970 and probably suffered post-traumatic stress disorder.

He scandalised Australia when he left his wife and child for Clift.

Australia was too provincial and conservative for the pair and they moved first to London and then to Hydra, where the cheap living allowed them to concentrate on their writing. Other artists got word of the lifestyle and drifted in.

Pretty soon the island was a hotbed of bohemianism, with open relationships, heavy drinking and long-winded intellectual debates raging through the nights.

Out of this came Johnston’s great Australian novel, My Brother Jack. But what was the personal cost of its production?

Sue Smith shows Johnston stifling Clift’s writing talents and emotionally dominating her into supporting his project. Nolan and his wife Cynthia Reed are foils to the awful drunken arguments between Johnston and Clift, which are punctuated by Johnston’s hacking, bloody, coughing fits.

Smith uses extensive sections of Clift’s and Johnston’s writing as monologues in the play, which is a marvellous device. It demonstrates that they were indeed great writers and passionate about the life they created, even though the pain of their choices tore into them.

Polly Samson presents a similar tale, though with a wider range of support characters. Cohen looms large with Ihlen.

Samson has extensively researched life on Hydra. She appears to have digested every biography of each protagonist. The character list is extensive, which makes it a bit hard at times to keep track of exactly who is sleeping with whom.

The fierce and hurtful Clift/Johnston relationship gets a good airing as does Cohen’s insensitive and selfish relationship with Ilhen.

A Theatre for Dreamers is well-written and a decent page-turner. But about half way through I suddenly realised that if the main characters were just called Ben and Molly and Jim and Ingrid, it would be deadly boring.

The Hydra artists colony was a high point of the cultural war against 1950s conservatism and its significance makes these two narratives interesting. The play is the more satisfying artistic endeavour, A Theatre for Dreamers suffers from the temptation to descend into gossip.