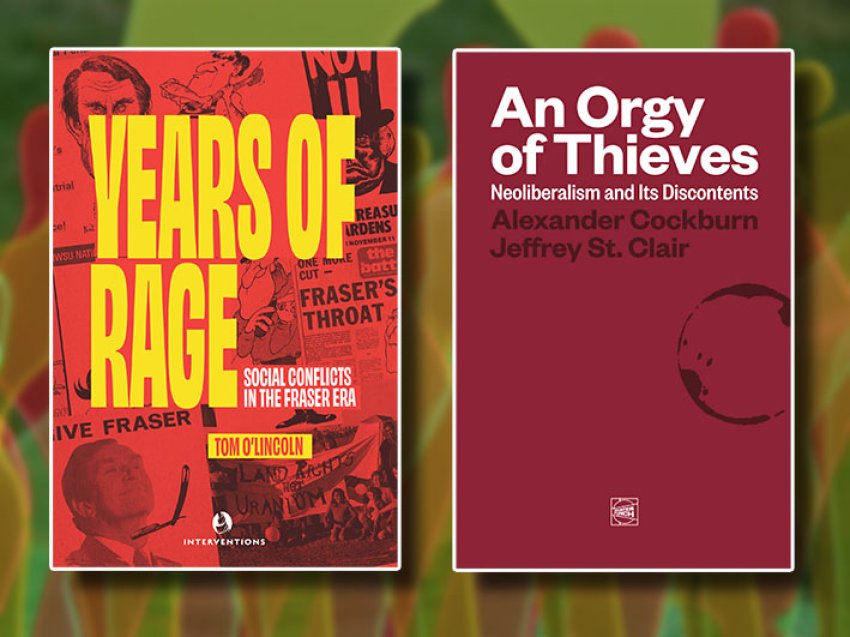

Years of Rage

Tom O’Lincoln

Interventions, 2023, $15

Orgy of Thieves

Alexander Cockburn and Jeffrey St Clair

CounterPunch Books, 2022

223 pages, $25.50

In reading Tom O’Lincoln’s book, Years of Rage, I was reminded of how far we have come since the 1970s — and not in a good way.

The kinds of struggles chronicled in the book — broad environmental, anti-uranium, women’s rights, Aboriginal land rights movements and more — should all have concomitant struggles today. But where is the social wage campaign to raise JobSeeker and build public housing?

Instead, we have former Labor Prime Minister Julia Gillard being feted as a feminist icon while stripping working class women of income support.

O’Lincoln’s book is not only a terrific historical document, it lays bare the strategies of liberal democracies, using the example of Australia in the 1970s and 1980s.

The decision of business to back the Bob Hawke government came after the myriad confrontations in the Malcolm Fraser years documented in the book, some of which were successful or were partial gains for the working class. Even that was too much for the ruling class.

Ultimately, Hawke was called on to bring the unions, which had won wage rises throughout that period, to heel.

This chimes with Orgy of Thieves, written by Alexander Cockburn and Jeffrey St Clair, which could be subtitled the Crimes of American Liberal Democracy.

Both books illuminate the integrated structure of capital and politics, specifically the roll-call of personnel that constitute the co-conspirators in the ‘redistribution’ of wealth away from those who produce it.

O’Lincoln’s book starts with an incisive chapter on who constituted the ruling class in Australia in the post-war period, up to the 1970s, including the Fraser years. In Orgy of Thieves, the authors detail different sets of relationships, but the comparisons are obvious.

With O’Lincoln focussing on a Liberal (read conservative) prime minister and the early Hawke years, and St Clair and Cockburn on the Democrats in the United States (Bill and Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama etc), the books help clarify the similarities between so-called parties of labour and conservatives as variants of liberal democracy.

The ways in which the Clintons and their cronies enabled key progressive US legislation (which had resulted from struggles in the 1960s and 70s) to be undermined, is covered in detail by St Clair and Cockburn.

The books part ways in discussing the trajectory of the years they cover, with the US book focussing on liberal betrayals, rather than working-class resistance.

The US approach underscores the lack of working class organising, the union movement having been smashed (with many unionists murdered) and co-opted years before. The US labour elites had already entered the era of legalistic challenges and lobbying, strategies which took root in Australia under Hawke and which are increasingly relied on now by so-called progressives — to the detriment of working-class resistance on both countries.

There are many examples in Orgy of Thieves of Democrat hypocrisy when it came to public policy. A stark one is that of a hazardous waste incinerator, built on a floodplain near schools and homes.

While campaigning to be Clinton's vice president, Al Gore opposed the granting of federal permit to the facility on environmental grounds.

When Gore gained office, the EPA granted the permit, with Gore betraying those who lived nearby and those who had voted for him. There was some resistance, with locals organising against it, who Gore promptly banned from attending presidential campaign rallies.

Overwhelmingly, the experience of resistance detailed in the US book is piecemeal and local.

The litany of Fraser’s attacks on the working class is detailed in Years of Rage. But its important focus is on working class resistance to ‘austerity policies’ — read policies which redistributed wealth upwards.

In this, the vacillations and ultimately, the complicity of the Australian union movement, is covered in detail. A good example of that is trade union leader Simon Crean, who, once Hawke had been elected to Parliament, stepped up a wages campaign while Fraser was still in office.

Crean then defused it once the 1983 election was called, announcing that Hawke had prevailed on him to show ‘restraint’.

Both these books are worthy additions to the historical record. If any progressives who call themselves socialists were ever drawn to support reformist politics as an actual strategy to advance working class interests, these books demonstrate that such a strategy will only lead to demobilisation.

[Maree F Roberts is an author, whose latest book is The Impossible History of Trotsky’s Sister.]