Hanging Ned Kelly: Elijah Upjohn, the hangmen and the underbelly of colonial Australia

By Michael Adams

Affirm Press, 2022

371pp

“Such is fame; to defy the whole police force of the colony for twenty long months, and be finished by a miserable chicken-stealer,” wrote the Ovens and Murray Advertiser, on July 10, 1880, following reports that a prisoner, Elijah Upjohn, was to be Ned Kelly’s hangman.

On the morning of November 11, 1880, Kelly, who had been condemned to die on the gallows at Melbourne Gaol, came face to face with first-time hangman, Upjohn.

Micheál Adams, historian and host of the Forgotten Australia podcast recounts the lives of Upjohn and other hangmen in his 2022 book, Hanging Ned Kelly: Elijah Upjohn, the hangmen and the underbelly of colonial Australia.

Upjohn was the latest in a long line of hangmen in colonial Victoria, who continued a tradition dating back to the first recorded hanging at London’s Tyburn gallows, in 1196. More than 50,000 people were publicly executed at Tyburn, until public execution ended in Britain in 1868.

When executioner, Jack Ketch, botched the beheading of Lord William Russell, in 1683, hangmen in Britain and throughout the colonies became known as “Jack Ketch”.

About a month after the arrival of the First Fleet launched England’s brutal colonisation of Australia in February 1788, the first hanging occurred in Sydney Cove. The first “Jack Ketch” was a convict forced into doing the job.

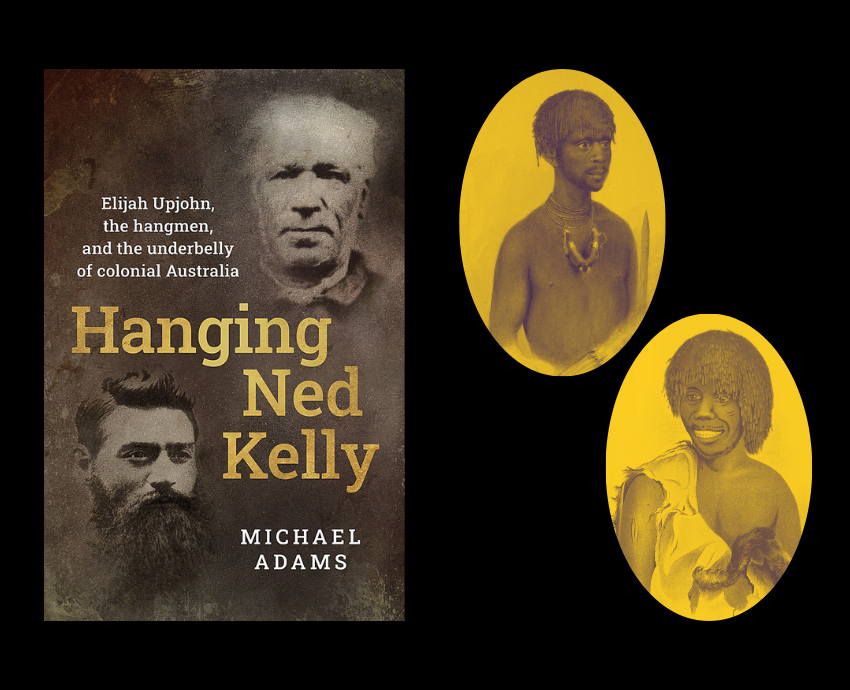

Colonial Melbourne’s first hanging took place on January 20, 1842. The two First Nations freedom fighters, Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner, originally from Tasmania, were sentenced to death for resisting the colonisation of their lands, massacres of their people and destruction of their way of life, in what became known as the Frontier Wars.

The jury convicted Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner, but recommended mercy. But the judge and government insisted on carrying out the executions. Ironically, the two men were defended by Sir Redmond Barry, later known as the “hanging judge”, who would sentence Kelly to hang in 1880.

Maulboyheenner’s and Tunnerminnerwait’s execution was attended by thousands of people. Like many future executions, it was botched. Maulboyheenner’s noose knot was displaced, and he was strangled to death.

There would be many more botched hangings even after the “long drop” method was adopted.

Adam’s goes into gruesome detail about the many executions that took place throughout 19th century Victoria, where crowds would clamour to see the spectacle. Despite public executions ending in Victoria in 1854, the year Kelly was born, the authorities would often let people into the prison to witness a supposedly private hanging.

Upjohn’s predecessors, such as Michael Gately, William Bamford and Jack Harris gained notorious reputations in 19th-century Melbourne for being drunk and disorderly.

Despite the ostracism the hangmen suffered, people clamoured to witness executions, devoured phrenologists' pronouncements about criminals, and crowded a Melbourne waxworks “chamber of horrors” featuring executed criminals.

In Hanging Ned Kelly, we follow the lives of Kelly and Upjohn. Upjohn was convicted in Dorset, England, at the age of 16 for stealing shoes and transported to Tasmania in 1839. While there, he was flogged for stealing a pair of trousers. Upjohn moved to Victoria in 1850, where he worked at times as a night soil carter and quack medicine salesman. He was arrested for stealing chickens in 1880, and while in Melbourne Gaol was appointed as Kelly’s executioner. After Kelly’s death, Upjohn was in and out of prison. He carried out floggings and hangings until 1884, when he was dismissed by the Victorian colonial government. He died a year later of suspected poisoning.

Adams has found that even after the adoption of the long drop method of hanging, up to 50% of executions were botched, including about 42% of hangings in Victoria between 1884 and 1922. Moreover, due to prejudicial judges, flawed evidence and the accused having limited knowledge of the law or legal representation, up to 75% of convictions and executions could be considered miscarriages of justice.

One of the most notorious unjust convictions is that of Colin Campbell Ross, a Melbourne wine saloon keeper who was convicted of rape and murder based on forensic evidence. Keith Murdoch’s Melbourne Herald led the charge to convict him. Ross protested his innocence but was hanged in 1922.

Years later it was found that the forensic samples turned out to be carpet hairs and that Campbell Ross couldn’t have committed the crime. He was posthumously exonerated in 2010. It was a gross miscarriage of justice.

Queensland was the first state to abolish capital punishment, in 1922, however, hangings continued in the rest of the country until 1967. Victoria finally abolished capital punishment in 1975, with all other states following suit by 1985 and in 2010 the federal government passed a law forbidding its reintroduction.

Adams concludes the book by asking how progressive and civilised Australia really is, and recounts the late 2021 right-wing “freedom rallies”, where marchers took selfies in front of gallows and nooses, concluding that while “Jack Ketch” is dead, sadly, his spirit remains

After Kelly was sentenced to death, thousands of people — many of them working-class — rallied and signed petitions for his reprieve. Hanging Ned Kelly exposes the colonial underbelly of Australia. It exposes how hypocrisy and brutality affected everyone, particularly hangmen forced to do the system's dirty work and why capital punishment and “Jack Ketch” should never return.