Australia is shaping up as the battleground for a showdown between corporate media giants, with the federal government keen to appear as if it is taking a stand for media diversity.

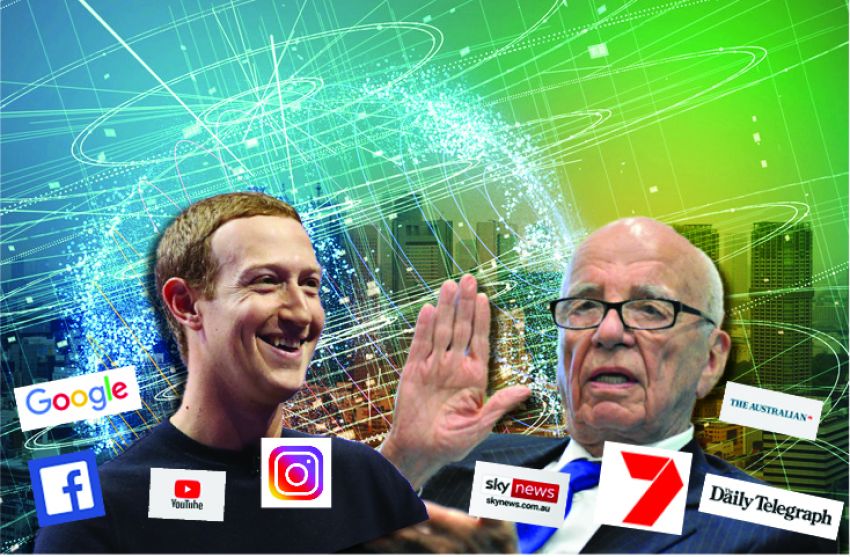

On one side are the federal government and corporate media giants News Corp, 9Fax (the merger of Nine and Fairfax Media Entertainment) and The Guardian. On the other are the online tech giants Facebook and Google.

The federal government wants the latter to pay royalties to Australian media companies for sharing news on their platforms. Its draft code of conduct has been met with fury by the tech giants.

At the heart of the dispute is how to make the most money from people increasingly accessing their news from online platforms. Traditional media, particularly print media, has been steadily losing advertising revenue to online companies.

According to a 2019 University of Canberra study, more than half the population now use Facebook and Google to access news, generated by traditional media companies.

More than 200 broadcast and print newsrooms have closed temporarily, or for good, since January last year, according to the Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance (MEAA).

This year, the COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to the suspension, or permanent closure, of more than 100 newspaper mastheads, many in regional areas. At least 1000 more editorial jobs are expected to go this year.

The government says it is concerned about all this. Yet, Australia’s newspaper industry is among the most concentrated in the developed world. The Coalition government tried to change the rules in 2016 that would have increased that concentration.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), which developed the new media bargaining code of conduct, said it addresses “bargaining power imbalances between Australian news media business and digital platforms, specifically Google and Facebook”.

The government says the new rules are an attempt to correct this imbalance.

But, while mandatory, it only requires media companies to bargain with each other and, only if there is no agreement after three months, will an arbitrator be appointed.

The ACCC accepts that the tech giants benefit more than the news companies, and that their market power means the latter do not have the capacity to demand a better deal. The September 5 Guardian said that one reason for the need for compensation is that “news companies are different because they compete directly with the platforms in the digital advertising market in a way other online businesses don’t”.

It said the decline of advertising revenue in the print media had led directly to the loss of thousands of journalism jobs and the closure of many publications.

The tech companies are not happy, and have come out swinging. Facebook announced on August 31 that if the new law was passed, it will ban publishers and those living in Australia from sharing local and international news on their platforms.

How it would do this remains unclear.

Google has used its Australian platforms, such as Google Search and YouTube, to tell users by direct message that such revenue-sharing laws would threaten its services.

Australian media groups often pay tax on local earnings, at a rate of up to 100 times greater than Facebook and Google. This makes any level playing field between local media and the tech giants impossible.

The MEAA, which covers journalists, welcomed the new media bargaining code, saying Google and Facebook must compensate media organisations for using their content. However, the union argues the draft bill needs more work to ensure that any compensation will be fairly distributed to encourage “public interest journalism”. It says the funds need to “benefit the ultimate creators of value, our journalist members, including freelance producers of media news”.

However, only the Guardian has said it would “invest more in local journalism” from any increased payment from the tech giants.

News Corp’s involvement in drafting aspects of the bill has raised more concern. If the legislation is passed, it will entrench its print media dominance. In 2016, News Corporation and Fairfax Media together owned the majority of national and capital city newspapers.

Another major concern is that the bill effectively cuts off a potential source of revenue to ABC or SBS. While the government moans about the cost of public broadcasters and plans more ABC budget cuts, it is not hard to be cynical about its claim to want to level the playing field and diversify the media.

Neither does the fact that it took no regulatory action over Nine Entertainment’s recent buy-out of Fairfax Media for $1.6 billion inspire confidence.

While the bill purports to want to increase media diversity, it is really about re-distributing payments from one set of giant corporations to another.

Even so, Facebook and Google’s threats are troubling: through sheer market power they want to veto any government bills that mandate them to give up a small part of their profits.

In the past financial year, Facebook paid less than $17 million in tax in Australia, while it recorded more than $674 million in profit. Google Australia made more than $4.3 billion in advertising revenue from its platforms and paid just $100 million in tax.

As long as the media giants can keep people on their platforms, they continue to profit.

Given the power of social media to manipulate public opinion, from the data collected from individual users through to the online manipulation of governments, and the threat this poses to democracy, there is a case for regulating the giant tech companies.

In addition, much more needs to be done to diversify the media. The public broadcasters need more funding, and democratically-elected boards would help with that as well as diversifying content.

A truly democratic society does require media organisations to be able to hold the rich and powerful to account. The proposed news media bargaining code will do nothing fundamental to change that.

[Jacob Andrewartha and Viv Miley are members of the Socialist Alliance.]