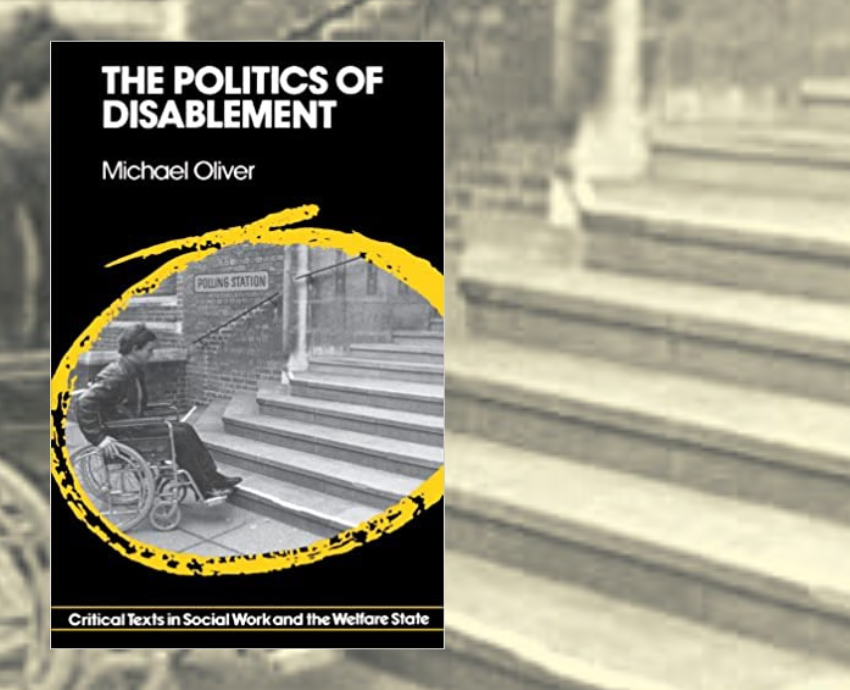

The Politics of Disablement: A Sociological Approach

By Michael Oliver

St Martin’s Press, 1990

The Politics of Disablement is considered a paradigm defining work for the sociological study of disability. The work is primarily concerned with explaining the production of the concept of disability under capitalism. In doing so, author Michael Oliver puts forward a common view disability self-advocates use, now termed the social model of disability.

Oliver relies on a materialist framework put forward by Karl Marx as refined by Max Weber and draws on the work of Michel Foucault to explain how the medical model of disability became dominant under capitalism.

The social model of disability holds that people with impairments are disabled by their treatment in society. Impairment is an innate condition of an individual, but disablement is the exclusion from society based on the impairment. Disability is identified therefore not in the individual, but in the ableist society. This is contrasted with the medical model of disability, which defines disability as a condition of an individual to be subject to social control and medical intervention.

According to Oliver, the rise of the medical model came about, in part, because of the need for capitalist governments to divide the unemployed working class into those who cannot work and those who wouldn’t conform to the new industrialised era of production. Disabled people were defined externally through diagnosis by medical practitioners. Diagnosis divided people into those worthy and unworthy of state support. In addition, both the worthy and unworthy poor were controlled through asylums and workhouses, respectively.

Oliver was not content to only explain the concept of disablement, but uses the framework to explain other concepts and how they came about in late capitalism. The concept of medicalisation, or “medical imperialism” is of importance to queer and disability advocates.

Medicalisation is the encroachment of medical explanations and solutions to problems formerly considered non-medical social phenomenon. A key example of medicalisation is the conception of homosexuality as a diagnosable mental illness. Officially removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) in 1974, it was replaced with a diagnosis for people who are “distressed by their sexual orientation” and finally removed from the DSM entirely in 2013.

Similarly, “gender identity disorder” was renamed in 2015 to “gender dysphoria” and the diagnostic criteria was changed to focus on distress arising from the incongruence between one’s gender identity and their assigned sex. Another pushback against medicalisation is the neurodiversity movement. The concept of neurodiversity reconsiders differences in brain function and behaviour as part of normal human variation rather than as “disorders” that need to be normalised through medical interventions.

Although The Politics of Disablement is a significant work, 33 years have passed since its publication. In that time there has been a fair amount of social progress with regards to disability rights. In addition, there is a predominant focus on physical disability, with limited discussion of intellectual disability and neurodivergence.

Readers may find Oliver’s The New Politics of Disability (2012) to be more relevant today. Or for a focus on the politics of neurodiversity, consider Judy Singer’s Neurodiversity: The Birth of an Idea (2016). Oliver’s original work would also benefit greatly from an analysis of the intersection between disability and other minority groups.