Love in Bright Landscapes

Documentary film by Jonathan Alley

Screening dates here

In the mid-1990s, Jonathan Alley, a Melbourne-based music critic, found himself transfixed watching a singer/songwriter and his band playing in a run-down pub.

“I was just astounded by the quality of his songs,” Alley told Green Left. “I was thinking: ‘Why is this man playing to a hundred or so people in a pub while Nick Cave is selling out arenas?’ He was every bit as good as Nick Cave.”

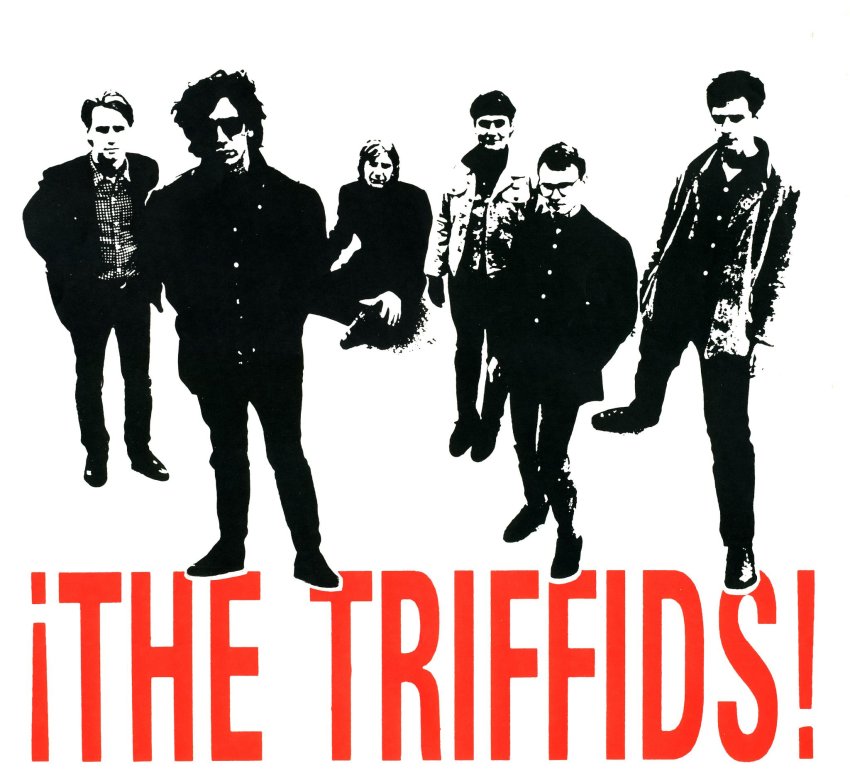

The singer was David McComb, who rose to fame leading the Triffids and went on to found the Black-eyed Susans, as well as solo projects. Now, with Love in Bright Landscapes, Alley has completed a 13-year long project to bring McComb the attention he deserves.

Funding for the film started from a tribute concert that Alley organised together with musicians who had known McComb.

The Triffids were a product of the 1970’s Perth punk/new wave music scene. Perth youth, living in what is said to be the most isolated city in the world, turned in on themselves in a tightly interwoven, rebellious music scene that produced several well-known bands.

WA drinking laws meant that, on Sundays, pubs could only open for three hours in the afternoon in what were colloquially called “sessions”. Pubs brought in bands to draw the drinkers and many musicians honed their skills on that circuit.

McComb came from a wealthy background. Both his parents were doctors, his father a renowned surgeon.

The family lived in a luxurious mansion on the banks of the Swan River and owned a sheep farm at Ravensthorpe. His father expected, having bestowed a private school education on his youngest son, that he would follow in his conservative footsteps.

But the young McComb was entranced by the rebelliousness of Lou Reed, David Bowie and the raw power of punk music and set out on his own path. However, the Triffids’ story is nearly a classic example of the tragedy of a talented band.

They carved out their own folk/rock sound, propelled by McComb’s songs that were drenched in Western Australian landscapes. His songs, such as his masterpiece, Wide Open Road still evoke the WA summer culture of beach, harsh sunlight and driving huge distances.

When they moved to London in the mid-1980's, it seemed the world was at the Triffids’ feet with the music press predicting their bright future.

The band toured endlessly, establishing a loyal European fan base. They worked hard and had dedicated management but could never cement the last element needed for pop success: a record company committed to them.

The Triffids found themselves playing large concerts, but promoting records that came out late.

Their life was characterised by arriving in strange towns and being welcomed by alcohol-fuelled lunches, hosted by local music industry representatives. After drinking into the evenings they needed stimulants to get them through the performance.

Then it was on to the next town where the cycle was repeated. What is worse, their record company intervened in the band, attempting to break it apart.

By 1989, the band had reached the end of the road.

McComb went on to solo recordings and to work with The Blackeyed Susans in Melbourne. But while fame eluded him, amphetamines, alcohol and heroin did not.

McComb had a heart transplant in 1996. He suffered from an inherited heart ailment, cardiomyopathy, which was certainly worsened by his drinking. By 1999, he was dead. The coroner found he had died of a combination of his body rejecting his new heart and heroin toxicity.

Alley has done a good job of digging out all sorts of images and interviews, and you can hear dozens of McComb's songs, personal letters and poetry throughout the documentary.

But Alley does not get to the real nub of McComb’s life: How can someone born with all of life’s advantages, blessed with prodigious artistic talent and the ability to mesmerise an audience, fail to achieve success? What kind of society industrialises artistic production while literally killing self-expression?

The capitalist entertainment industry, that giant machine that consumes talent at one end and spits out commodified mediocrity at the other, used up McComb like it has so many others.

But his life was greater than mere tragedy. McComb’s achievement is in the catalogue of his works, which, as can be seen in this film, still lovingly draws people, to his memory.

[Watch the trailer here.]