At a time when governments appear increasingly out of touch with the people they represent, and many of those people are losing faith in what is served to them as “democracy”, a politician who is taking action to reverse this trend needs every bit of encouragement that we can give them.

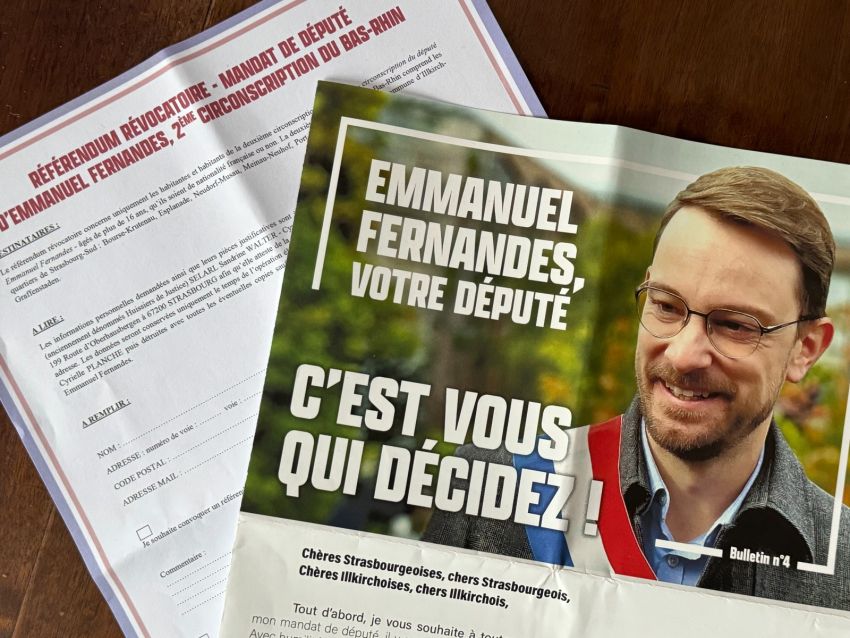

In this case, the politician is my local La France Insoumise (LFI) Deputy, Emmanuel Fernandes.

Fernandes was elected to represent southern Strasbourg at the National Assembly in the 2022 general election. One of his campaign promises was that he wouldn’t wait the full five years of his mandate to make himself accountable to voters, but would submit to the possibility of a recall referendum halfway through his term.

Although his election win was very close — he narrowly beat the Macronist incumbent with 51% of the vote on a 47% turnout — he has kept his promise, and the people of Strasbourg are now being given the opportunity to judge his performance.

Recall

The rules are simple. He is asking all Strasbourg residents to complete a form if they would like a recall referendum to take place. If more than 10% of residents complete and submit this form, a referendum will be organised within six months.

Provided more than 25% of those eligible participate in the referendum, our Deputy’s future will be decided on a simple majority. If the majority ask him to go, he will step down.

To keep everything above board, votes must be accompanied by proof of identity and address, and they will be counted by a commissaire de justice, a public official.

Last week I caught up with Fernandes in the Council of Europe, where he is part of the French delegation to the Parliamentary Assembly, and asked him about his democratic experiment. He explained that the idea of a recall ballot was part of the party’s program for a new constitution and a Sixth Republic, “because when you don’t stick to what you promised people should have the possibility to revoke your mandate”.

Fernandes is not the first LFI MP to offer a referendum on his performance. In the previous parliament, François Ruffin encouraged his constituents to petition against him if they were not happy with his first year in office, providing them with a form with which to do this.

But Ruffin set the bar much higher. His was a more basic system: he simply promised to resign if 21,000 people — approximately a quarter of the constituency’s registered voters — signed the petition for him to go.

I asked Fernandes to tell me how they came up with the percentages he is using. He explained that 10% of the electorate is the percentage needed to demand a national referendum. The 25% rule for the referendum is to ensure that it is sufficiently representative.

The party wants voting to be more inclusive, and he is practising this by extending the voter list for this referendum to include 16- and 17-year-olds and also residents (like me) who are not entitled to vote in France. About 12,000 people would need to fill in the initial form for the referendum to go ahead, and this would then need around 30,000 votes in total to be accepted. Just over 33,000 people voted in the second round of the general election.

One unfortunate result of the way this opportunity to revoke the mandate has been organised is that, because it is only people who want a referendum who are expected to fill in the form, it is only the comments of opponents that will be collected in the comment box. While some of these may be useful, it is, perhaps, a lost opportunity to gather a more balanced collection of views. Fernandes said it will be interesting to see what people write, but that he knows that most people wanting a referendum will have been his opponents since before the start of his mandate.

People can submit the forms demanding a mandate online or by post, or at one of four day-long street stalls to be held in different parts of Strasbourg.

Serve the people

Fernandes admitted that while some people have found the referendum a good initiative, others have considered it too risky, but he said, “I think that it’s never risky to give the possibility to the people to express their will, and that I am only here to serve the interests of the people”.

The LFI’s manifesto calls for this type of referendum, but Fernandes explained that the actual form of the new constitution they are demanding cannot yet be known because it would be written by a constituent assembly. The chance of this happening is still a long way off, but, as Iceland and Chile can sadly testify, writing a radical new constitution is easier than getting it accepted and made reality.

When I moved to France, I couldn’t understand why it seemed impossible to join LFI. Nobody explained to me that they don’t work on a membership system, but try to be open and inclusive in their internal democracy too. As Fernandes put it, “We are a political movement that has windows and doors wide open to citizens”. Anyone who is interested can join their local activist group, and representatives from the groups attend a national gathering. The party manifesto, which was written for Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s first presidential run in 2017, was itself based on a lot of work with civil society groups, and it is updated through this activist organisation.

When I asked Fernandes how they reached decisions on things not in the original manifesto, such as their stance on the war in Ukraine, he explained, “it’s also a question of who we are, what we are … Our position was already there before the war … that France should have a non-aligned position … We should have our own voice in the world”. He also explained that a first step would be to remove France from NATO’s integrated military command, as General de Gaulle had done in 1966, and that Nicholas Sarkozy had reversed.

Fernandes was chosen as a parliamentary candidate at a meeting of activist groups, where the different people vying for the role presented themselves and their ideas, and the decision was made by consensus after discussion. MPs cannot assume that they will be reselected as candidates for the next election.

Fernandes’ supporters have no reason to criticise their very hard-working representative, but his hard work for progressive causes may not play so well with those who voted for his opponent, so this democratic experiment contains a very real risk. However, it is heartening to see a sincere attempt to take democracy seriously.

Strasbourg prides itself on being the city of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law because it is home to the Council of Europe.

Last week, left wing and progressive members of the Council’s Parliamentary Assembly — including Fernandes — were shocked and horrified when that Assembly, which exists to protect human rights, passed a motion that effectively green-lighted Israel’s genocide in Gaza.

It is, thus, particularly gratifying to see that political integrity is still keeping up the struggle to survive in this beautiful city.

[Sarah Glynn is a writer and activist — visit her website and follow her on Twitter/X.]