Pressure from United States President Joe Biden’s pledges on swift climate change action seems to have pushed Scott Morrison to mention that the government does indeed have a plan to reduce emissions.

“Our goal is to reach net zero emissions as soon as possible, and preferably by 2050,” Morrison airily told the National Press Club on February 1.

Until now, Morrison has prevaricated. When asked about emissions targets he would snark, “As quickly as possible”.

What is possible, however, is being made very obvious by Biden’s executive orders. Biden is no radical Democrat leader, but the comparison with Australia makes him seem so.

Biden has promised to: rejoin the Paris Agreement to stay under 1.5°C warming; impose a moratorium on new oil and gas leasing on US land and water; set more areas aside for conservation; establish an office to “serve low-income and minority communities that disproportionately suffer from air and water pollution”; and establish a climate finance plan to “assist developing countries in their emissions reduction measures while protecting critical ecosystems and building resilience”.

In addition, he has pledged to buy “carbon pollution-free electricity and clean, zero-emission vehicles to create good-paying, union jobs and stimulate clean energy”.

Biden has also announced that the US will host a summit of climate change leaders on Earth Day, in April.

The Biden team’s overall view is that the climate scientists have “made clear that the scale and speed of necessary action is greater than previously believed”. The US government now says, “There is little time left to avoid setting the world on a dangerous, potentially catastrophic, climate trajectory.”

It also said: “Responding to the climate crisis will require both significant short-term global reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and net-zero global emissions by mid-century or before.”

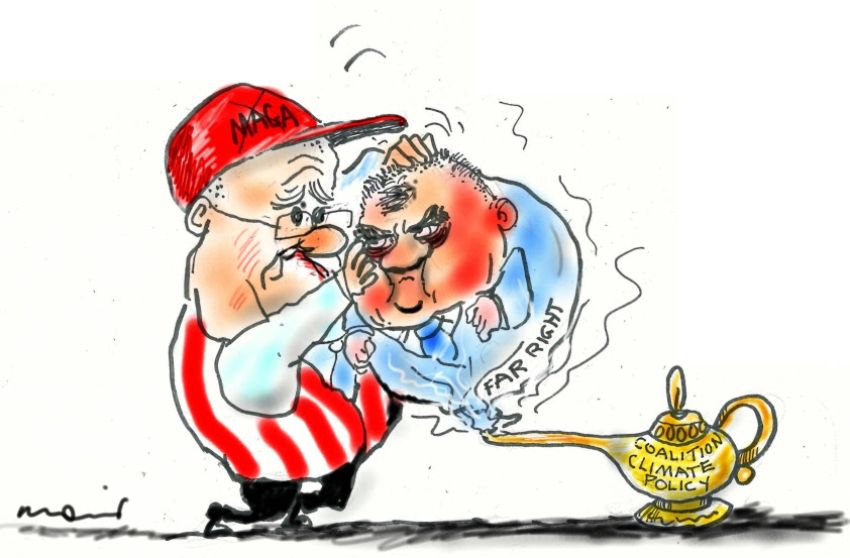

This is a big about face. And it leaves Morrison and Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese scrambling to catch up. Both still refuse to outline plans as to how we can get to net zero emissions by 2050, which they both now purportedly support.

Climate experts and some community-union organisations can see a road ahead and are sketching it out. Private capital has too, of course.

One in four Australian homes now produces solar energy, prompted in large part by individuals looking for ways to bring down their large and rising energy bills. (Big business still has much of its energy costs subsidised by the public purse.)

According to the government’s own projections, it will overshoot its inadequate 2030 emissions targets of 26–28% below 2005 levels. This is because of its economic plan to recover from the pandemic by expanding the gas industry. There has also been a rise in emissions from the transport sector and industrial emissions, the government has reported.

Earth System researcher Will Steffen told the ABC’s 7.30 on January 28 that he believes it is now “virtually impossible” to keep the temperature rise to 1.5°C warming — the Paris Agreement’s aim.

“We were warned 10 years ago that, if we wanted to meet what turned out to be the lower Paris target of 1.5, we had to start getting emissions down during this past decade. We didn’t do that. That means that it is virtually impossible now to hold [the] temperature rise to 1.5.”

He said that keeping warming under 2°C — “a pretty difficult climate to live in” — means that there can be no more delays in taking action. He said the targets currently being talked about need to be doubled, at least.

“The present targets are 26 to 28% emission reduction by 2030 on 2005 levels. That is far, far too weak … At the very minimum, we need to cut our emissions by 50%, not 26 to 28%, by 2030, and that means we need to get them headed down quite strongly by 2025.”

Steffen, along with two other climate scientists and former Liberal Party leader John Hewson, released a report on Australia’s Paris Agreement Pathways in January. Concerned that the Climate Change Authority (CCA) — which is supposed to set out targets — had not produced a report, nor updated its research, since 2014, they decided to do one based on the CCA’s methodology.

The report’s authors sketched the targets Australia would need to be consistent with Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to 2°C. They concluded that Australia’s 2030 emissions target must be 50% below 2005 levels, its 2035 target would need to be 67% below 2005 levels; and net zero would need to be reached by 2045.

“A simple ‘net zero emissions target by 2050’ is not sufficient for the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to well below 2°C (nor 1.5°C),” they said.

To do its “fair share” and remain compliant with the Paris Agreement goals, Australia must in fact strengthen its emissions targets.

The CCA concluded in 2014 that Australia needed to first consider the global emissions budget available if the world was going to limit global warming to 2°C and then derive Australia’s carbon budget from that.

It concluded then that Australia’s “fair share” was 0.97% of global emissions and recommended a “trajectory range of [between] 40 to 60% below 2000 levels”, which Steffen calculated translates to 45–65% below 2005 levels.

The CCA said at the time: “This range allows Australia to step up efforts if stronger global action emerges or to moderate them if weaker global action makes more than 2° of warming likely. It also maintains flexibility to respond to new information about climate science and developments.”

No wonder the CCA has been sidelined.

The CCA predated the Paris Agreement, but when Tony Abbott became Prime Minister he set about undoing the Kevin Rudd-Julia Gillard climate measures.

Steffen and his colleagues note that there is “significant debate” among climate scientists on whether it is still possible to keep global average temperature rise below 1.5°C, given that the world has already warmed by 1.1°C.

Australia’s main trading partners Japan and South Korea have committed to net-zero by 2050 targets, and China has committed to net zero by 2060. This puts pressure on Australia’s exports, including coal.

Steffen said Australia needs to update its emission reduction targets with weighted pathways and that adopting a “straight line” projection from 2020 to 2050 would not result in the cuts required. Without stronger early targets, adopting a net zero by 2050 target is “incompatible” with the Paris Agreement.

What is clear, Steffen told 7.30, is that, “There is absolutely no room for the expansion of the fossil-fuel industry.

“To meet these Paris targets, to get the emissions down by 50% by 2030, we have to rapidly reduce our use of fossil fuels — coal, gas and oil. And that means you simply can’t expand any of these industries.”