Black Against Empire, the History & Politics of the Black Panther Party

Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin Jr, University of California Press, 2013, 560 pp., $54.95

The United States in the 1960s was a tinderbox of unresolved racial tensions. With Jim Crow racism dominating the South and oppressive police patrolling the northern ghettos, Martin Luther King’s Civil Rights Movement ignited hopes for change nation-wide.

The ruthless violence unleashed against King’s passivist democratic movement radicalised its youth leaders. Malcolm X, first as a Black Muslim and then as an increasingly left-moving revolutionary, came to articulate the desire of many for armed self-defence.

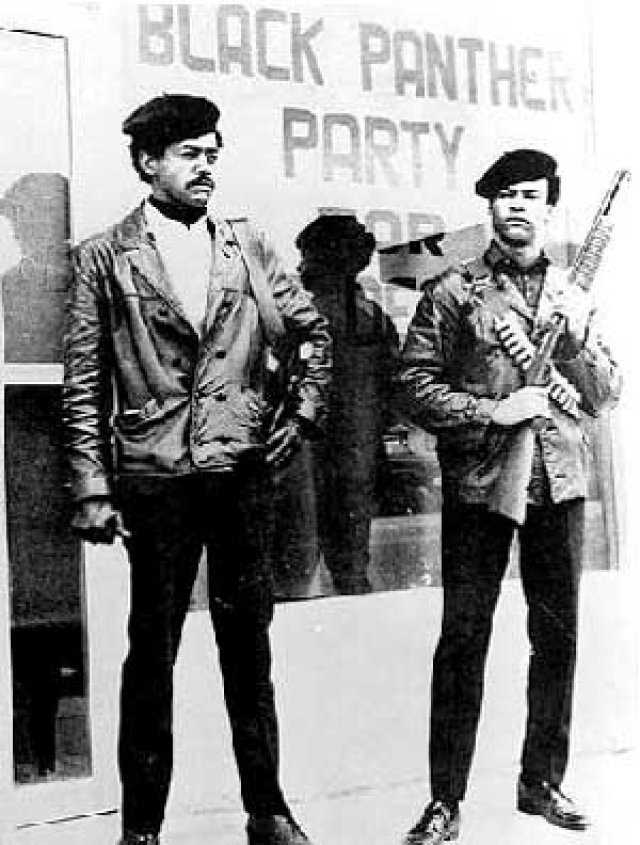

After Malcolm’s 1965 assassination, the Oakland-based Black Panther Party for Self Defense (BPP) articulated this widely felt rage. Organised and led by Huey P Newton and Bobby Seale its openly armed community patrols defied the viciousness of the local police.

Slowly but surely, their example inspired the community to rally against the cops in some dramatic showdowns. The Panthers spread to another 68 cities, where chapters were formed.

Before they knew it the Panthers were the linking up with white student radicals grouped in the Students for a Democratic Society and a heady brew of strident confrontation with authority became the standard of their political life.

Joshua Bloom and Waldo E Martin write in this minutely researched history that many young people “came to dedicate their lives to the Black Panther Party and embrace armed revolution”.

As the youth revolt against the Vietnam War grew the Panthers' heroic stance drew many activists towards revolutionary politics. The Panther’s weekly newspaper reached a circulation of 250,000 at its peak, a measure of the support that they generated among Blacks and beyond.

However, it wasn’t just radicals paying attention. The capitalist power structure rallied behind the verminous character of Richard Nixon who swept to power in the 1968 presidential election.

Nixon encouraged police across the country to attack, murder and frame Panthers nation-wide.

The entire state apparatus, from the FBI down to state and local authorities were coordinated in the ferocious attack. Legal niceties were dispensed with; this was rough justice, bourgeois-style.

Within two years, 28 Panthers were dead, many others caught up in long, drawn out court battles and Panther allies like Angela Davis persecuted out of their jobs. Newton’s epic series of appeals against his frame-up murder conviction became the era’s cause celebre, with “Free Huey” a rallying cry.

As Bloom and Martin chronicle, support for the Panthers actually grew during this period of repression. However, the Panther’s became disorientated by their need to fend off the state and broaden their circle of allies while maintaining their identity as the staunchest militants standing up to the white power structure.

The high point of Panther success was when Newton, newly out of jail in 1971, headed a Panther delegation to China for official talks with Premier Zhou Enlai. The US government still officially did not recognise the existence of the People’s Republic of China at the time, making this was an unparalleled political and diplomatic coup.

Other international links were forged. The Cubans provided military training and political asylum to Panthers fleeing US authorities. The North Vietnamese government sent letters from US POW’s back to their families via the Panthers and, according to Bloom and Martin, offered to exchange POW’s for Panther political prisoners in the US.

Perhaps the Panthers’ greatest internationalist achievement was the establishment of an officially recognised embassy in Algeria where their international section was headed by Kathleen and Eldridge Cleaver.

Unfortunately, the Panthers were so politically naive they did not realise the Chinese Stalinists were using them as a pawn in their longer term plan to force the US government into diplomatic relations.

As soon as Nixon visited China, the Panthers dropped off the Chinese Communist Party’s radar with the rest of its “anti-imperialism”.

Cleaver, from afar, split the Panthers by encouraging members to go underground in the service of the Black Liberation Army. The BLA was to work in concert with the Weather Underground, an ultra-left spit from SDS.

Bloom and Martin’s account of the BLA is a little confusing. At one point they seem to say that it was a Panther off-shoot, which members were encouraged to join. At other times it seems like it was organised by disaffected members itching to “off the pig” (a favourite Panther slogan).

Ex-Panther and BLA member Assata Shakur, (who recently became the first woman to be placed on the FBI’s “most wanted terrorist” list over a police shooting she was framed for in the 1970s) described the BLA as “not an organisation … It is a concept”.

In other words, it was a disparate movement with no effective leadership. BLA activists robbed some banks and engaged in some violent attacks on police before they were finally extinguished in the early 1980s, around the same time that the Black Panther Party closed its last office.

While the BLA was engaging in shoot outs with cops, the BPP was trying to get back to basic community political organising, with some success. However, the personal degeneration of its leaders and the changed political atmosphere stifled it.

Bloom and Martin have produced the bedrock history of all these events, but they have failed to provide an effective political analysis. They write from a self-declared Gramscian perspective, which seems to lead them into some odd intellectual contortions.

For them “revolution theory splits the world in two” while “the people in power and the institutions they manage are the cause of oppression and injustice”.

This does not accord with conventional Marxist theory, which explains why there are splits in the world (but does not produce those divisions). Similarly capitalist social institutions and their representatives reflect (and then reproduce) the underlying social oppression and injustice.

These elements of Marxism are important in relation to the Panthers, because, despite their proclaimed revolutionary thinking, they made some fundamental errors of judgement.

Lenin famously explained in his writings about ultra-leftism that it is vital to allow the masses to go through the political experiences that lead them to revolutionary conclusions. The Black Panther Party made the classic error of substituting their prodigious bravery for the action of the masses.

Russian revolutionary leader Vladimir Lenin also explained what elements make up a pre-revolutionary situation: a political crisis, a paralysis among the rulers, confidence among the masses and a unified party to lead the struggle.

In the US of the late 1960s, there was certainly a crisis caused by the Vietnam War and the struggle against domestic racism. There were also large numbers of revolutionary minded youth.

However, the ruling elite, while troubled, was not paralysed. It united around Nixon and served up extra-legal repression to its enemies.

Most importantly, most Americans, while they could have been won to revolutionary politics by a wise political program, were not interested in “revolutionary violence” in the streets.

They wanted change and rallied to the anti-Vietnam War movement when it focused on their desire for an end to the war using peaceful and legal methods.

Intelligent revolutionaries may have built a new working-class leadership out of that movement, but far too many youthful radicals were impatient and tried to skip over the vital steps to the end they desired.

This all occurred in the context of severe state repression that worsened such impatience.

Such was the tragedy of the Black Panther Party and the young radicals it inspired.