Egyptian scholar and researcher Samir Amin spoke with Hassane Zerrouky on the Arab revolts that have broken out this year, for L'Humanite. The interview was translated by Yoshie Furuhashi for www.mrzine.org . Abridged version appears below.

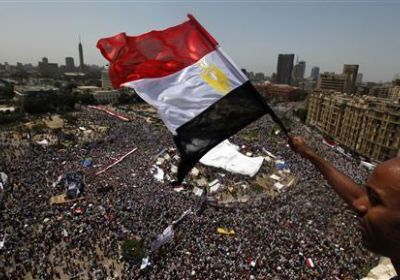

What's happening in the Arab world six months after the fall of dictator Ben Ali in Tunisia?