Greens leader Richard Di Natale raised the prospect of a “four-day work week or a six-hour day” as part of an address to the National Press Club on March 15.

This is a good discussion to be having in a country where people work among the longest hours in the world and where productivity growth has massively outstripped wage growth in recent decades.

Di Natale also flagged the possibility of a Universal Basic Income — which he described as a “guaranteed adequate income”.

He did not advocate for any particular model or advance a specific policy proposal. Instead he suggested we should “kick off a conversation about the future of work” with “discussion” about some of these possibilities.

This is a welcome and refreshing development in a political landscape dominated by the Liberals' “jobs and growth” mantra echoed in different words by the Labor opposition.

The establishment focus on “jobs and growth” is partly a fig leaf to cover their unrestrained mission to boost corporate profits above all else. However, it also reflects the fact that more and more people are feeling the insecurity of the current post-mining boom employment landscape.

This is true both for people desperately seeking more hours or a permanent position as much as for those putting in massive amounts of overtime, often unpaid.

In theory, Australia has a 38-hour week. However, most full time workers work considerably more than that. Almost one-third work more than 50 hours a week.

Even worse, full time workers put in an average of five hours a week of unpaid overtime according to a 2016 survey. This represents 14% of their work time. If it were paid for, corporate Australia would be handing over $116 billion extra a year to Australian workers.

Latest indications are that overtime is on the rise. A shorter working week is an obvious answer to these problems.

But it is not just the imbalance between those working too much and those working not enough. According to Philip Sopher in The Atlantic: “A growing body of research and corporate case studies suggests that a transition to a shorter workweek would lead to increased productivity, improved health, and higher employee-retention rates”. A four day workweek could also “help lower blood pressure and increase mental health” according to the president of the British Faculty of Public Health.

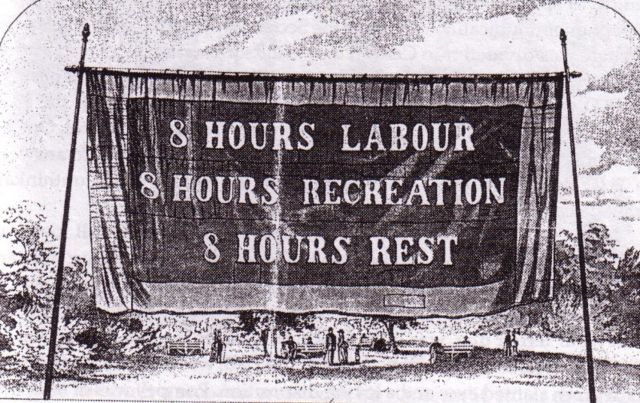

Sopher also points out that the long term trend is for a reduction in work time from the 16-hour days common in Dickension England through the 10-hour day, the eight-hour day, the relatively recent convention of a two-day weekend and more recent efforts to reduce the workweek further.

However, many workers might instinctively feel that a shorter workweek with no loss in pay is an unrealisable goal. After all, we have just seen a brutal cut in Sunday penalty rates for many workers due to come into effect in July. This seems to more like the current trend in industrial relations.

Australian stonemasons were the first in the world to win the eight-hour day, in the context of a labour shortage in 19th century Australia. However, more recently in the 1970s and ’80s, Australian unions began a concerted and partially successful campaign for a shorter workweek.

The then-Amalgamated Metalworkers and Shipwrights Union led the campaign for a 35-hour week with strikes, stopworks, monthly meetings, an information booklet in seven languages and a ban on overtime. One feature was a monthly strike.

The Labor Party — preparing for government at the 1983 election — refused to support the demand. In the end a compromise was reached that involved a pay rise and the introduction of the 38-hour week.

Twenty years later, construction workers in Victoria won a 36-hour week, again by taking industrial action until the bosses were forced to concede. This has not been generalised because Labor — as a party representing corporate interests — refuses to support such campaigns and uses its influence in the union movement to actively suppress them.

That's what makes the Greens' initiative to begin this discussion so valuable.

We need to raise the issue both politically and also within the union movement.

[Alex Bainbridge is a co-convener of the Socialist Alliance.]

Like the article? Subscribe to Green Left now! You can also like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.