What Aboriginal people ask is that the modern world now makes the sacrifices necessary to give us a real future. To relax its grip on us. To let us breathe, to let us be free of the determined control exerted on us to make us like you … recognise us for who we are, and not who you want us to be.

— Galarrwuy Yunupingu, Final Report of the Referendum Council, June 2017.

If you have come here to help me you are wasting your time, but if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.

— Lilla Watson

* * *

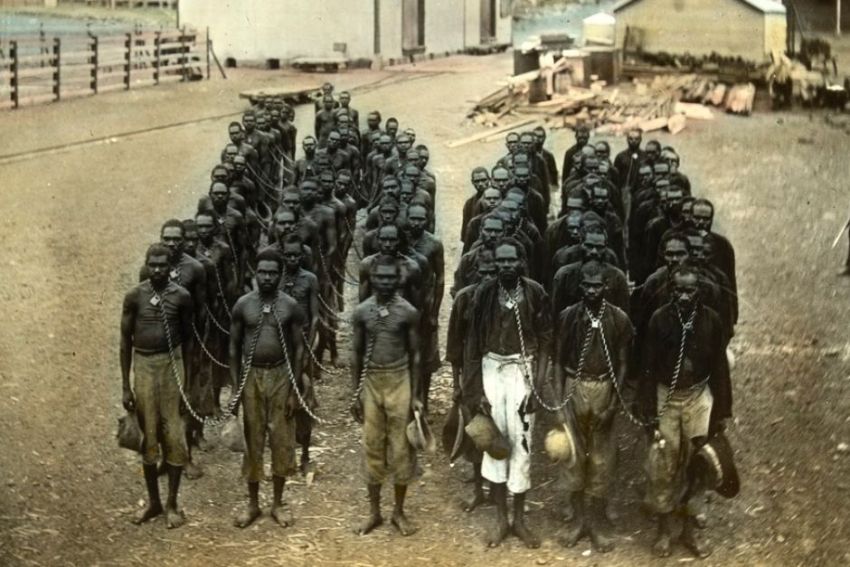

The Frontier Wars, which lasted from 1788 until 1934, included massacres and other genocidal practices such as the dispossession of land from Indigenous peoples, sacred and hunting grounds, and devastation from introduced diseases and food poisonings.

Fundamental to Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal relations is the division between those who view the British Crown’s claim to the eastern seaboard of Australia as an act of settlement, as opposed to First Nations peoples and their supporters who see it as an invasion.

The 2017 Final Report of the Referendum Council refers to a division between “old” and “new” Australians. The invasion, that began at Botany Bay, is the origin of the fundamental grievance: this land was colonised without the consent of its rightful owners.

As the report states: “Their land and sovereignty was annexed without consent and without treat(y) with the country’s rightful owners.”

It is worth noting the weaponised hostility from the colonial settlers toward the Indigenous people dates from 1770. In his book James Cook, Peter Fitzsimons reveals that Cook’s own journal records that local people were agitated by a strange vessel entering Botany Bay. Cook also admits to firing three musket shots, one of which wounded an Indigenous man. From the very first encounter, the unannounced visitors made their intentions known with the force of arms.

Frontier Wars

This initial antagonism set the tone for the fighting which started several months after the First Fleet landed in Botany Bay in January 1788, and ended with the last direct clashes recorded as late as 1934. Historian Henry Reynolds has said in Forgotten War that at least 40,000 Indigenous people and between 2000 and 2500 settlers died in the Frontier Wars.

The impact of colonisation on the number of Indigenous peoples is even more dramatic. Before 1788, an estimated 300,000 to 1 million Indigenous people lived here. By 1920, this may well have dropped to as low as 80,000.

In the preface to Blood on the Wattle, Bruce Elder states that: “The massacres of Aborigines … should be as much a part of Australian history as the First Fleet, the explorers, the gold rushes and the bushrangers.”

While the Frontier Wars may have ended to 1934, one form of violence and control became another as the government later deployed new policies of control and discrimination.

Aboriginal people were herded onto missions and reserves on the fringes of white settlement and the Stolen Generations were taken from their families. This was the policy of assimilation.

As emphasised by Australians Together, the assimilation approach “proposed that ‘full blood’ Indigenous people should be allowed to ‘die out’ through a process of natural elimination, while “half-castes” were encouraged to assimilate into the white community.”

White Australia policy

Coinciding with the latter years of the Frontier Wars, the colonisers formed a Federation under a Constitution which, among other things, was heavily influenced by the White Australia Policy.

This policy, based upon the assumption of the superiority of whiteness, allowed for the passing of the Immigration Restriction Act 1901. This effectively stopped all non-European immigration and contributed to the development of a racially-insulated white society.

From the beginning, white Australia believed that the Aboriginal people were a dying “race” and the Constitution only made two references to them. Section 127 excluded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from the Census and Section 51 (xxvi), regrettably, gave power over Aboriginal people to the states rather than to the federal government.

It took 66 years, and a referendum in 1967, requiring a majority of the voters in a majority of the states to include Aboriginal people in the Census.

Aboriginal peoples’ calls for recognition refused to go away. People of particular note who have fought for Aboriginal rights, include William Cooper, who was one of 11 signatories to the Maloga Petition in 1887. During the 1930s, Cooper and other leaders from the Australian Aborigines' League collected 1814 signatures and petitioned Prime Minister Joseph Lyons and King George VI to intervene on behalf of Indigenous Australians “for the preservation of our race from extinction and to grant representation to our race in the Federal Parliament”.

Aboriginal activists Fred Maynard and Tom Lacey founded the Australian Aboriginal Progress Association in February 1925, which advocated for the right of Aborigines to determine their own lives.

Lack of treaty

Australia is the only Commonwealth nation where a treaty between the colonisers and the Indigenous people has not been forged. An Indigenous treaty was first promised by Prime Minister Bob Hawke, back in 1988 after receiving the Barunga Statement from Aboriginal elders which called for such a treaty to be concluded. No treaty eventuated.

The continued lack of a treaty with Indigenous Australians shows an ongoing denial of the prior occupation and dispossession of Indigenous people and a general disregard for their rights and aspirations. It is a reminder that oppressive colonial attitudes have not been addressed.

In the 1990s, Australia sought a policy of reconciliation. Reconciliation processes are often criticised for demanding that the victims of state repression relinquish their legitimate claims to justice for the sake of national unity.

Wiradjuri man and author Kevin Gilbert expressed it this way: “What are we to reconcile ourselves to? To a holocaust, to a massacre, to the removal of us from our land, from the taking of our land? The reconciliation process can achieve nothing because it does not … promise justice. It does not promise a Treaty and it does not promise reparation for the taking away of our lives, our lands and our economic and political base. Unless it can return to us those very vital things…what have we? A handshake? A symbolic dance? An exchange of leaves and feathers or something like that?”

For Gilbert and many others, the possibility of breaking with the colonial past depends on the recognition of Aboriginal sovereignty.

But if the legitimacy of the Australian state rests on the presumption that there was no recognisable legal or political organisation prior to the arrival of the British Crown, Aboriginal sovereignty fundamentally challenges terra nullius.

A common misunderstanding is that the Mabo decision of June 3, 1992, recognised Aboriginal sovereignty. It did not.

As Reynolds put it in his 1996 book Aboriginal Sovereignty: Three Nations, One Australia: “[While] the court demolished the concept of Terra Nullius in respect of property, it preserved it in relation to sovereignty ... For 200 years Australian law was secured to the rock of Terra Nullius. One pinioned arm represented property, the other sovereignty. With great courage the High Court recognized native title in the Mabo judgment and released one arm from its shackles. The other remains as firmly secured as ever and seems destined to remain there for some time but in the long run the situation will prove unstable. What is more, the resulting legal pose will become increasingly uncomfortable as time passes.

Sovereignty never ceded

Critics of the formal reconciliation process say it was a further stage in the colonial project to assimilate. Many Aboriginal people insist that their sovereignty was never ceded. This claim represents both an assertion of the right to self-determination and a refusal to recognise the legitimacy of the settler-colonial state that has incorporated them as citizens.

Reynolds has stated that any discussion about the evolution of Australian nationalism must recognise sovereignty. But this discussion comes with a warning: the word has a different value depending on who you are. For Aboriginal Australia, sovereignty has never been ceded.

According to the Uluru Statement from the Heart, sovereignty is a spiritual notion. It is the “ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’ and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples”.

The quest for Aboriginal sovereignty challenges non-Indigenous Australia to let go of any perceived right to define what sovereignty is, and for whom.

This, I suggest, is why the Uluru statement includes the assertion that Indigenous sovereignty “co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown”. Sovereignty has a dual character: one that is non-Indigenous and another that is Indigenous. The search for liberation through sovereignty can only be achieved with both sides working together.