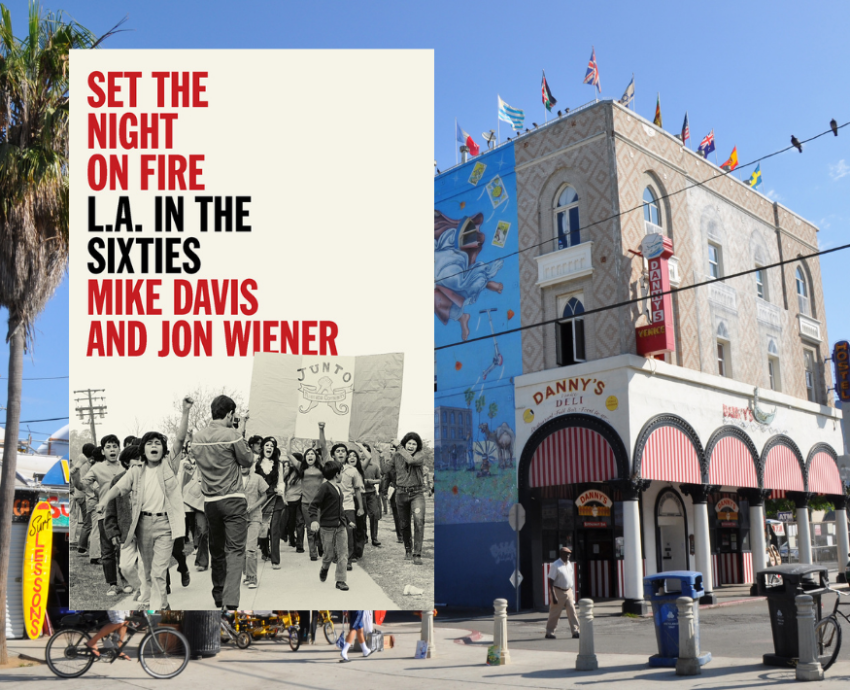

Set the night on Fire: LA in the Sixties

By Mike Davis and Jon Wiener

London, Verso Books, 2020, 800pp

The popular image of Los Angeles is a glamorous city of film stars, freeways and wind-swept palm trees.

But this image bears little resemblance to reality. LA is a largely working-class, viciously unequal and still segregated city of Black and brown people, immigrants and other marginalised groups whose struggles have come to define the radical history of the city.

Set the Night on Fire: LA in the Sixties focuses on the radical activism of these communities between 1960 and 1973 as they fought against racism, oppression and poverty.

The book is a collaboration between LA based activists and historians Mike Davis and Jon Wiener. Davis has written two previous books on LA: City of Quartz (1990) and Ecology of Fear (1999), while Wiener is known for his work exposing the FBI’s files on John Lennon.

LA’s radical movements experienced a revival in the early 1960s with young African-Americans playing a crucial role in these early struggles.

Organisations like the Southern Californian chapter of the Communist Party USA and the LA chapter of Women Strike for Peace, founded in 1961, were also crucial in the development of LA’s civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements.

The civil rights struggle in the deep South inspired the formation in 1963 of LA’s United Civil Rights Committee (UCRC) — a united front of activists who demanded desegregated housing, jobs and education.

The UCRC successfully pushed the passage of the California Fair Housing Act in 1963 which prohibited racial discrimination in both public and private housing.

But there was an immediate racist backlash from California’s white, conservative establishment.

The California Real Estate Association, the LA Police Department (LAPD), the Los Angeles Times, and reactionary mayor Sam Yorty (1961–73) campaigned for Proposition 14 — an amendment that effectively re-legalised housing discrimination. Proposition 14 passed in a 1964 referendum, thereby repealing the Fair Housing Act.

This defeat for LA’s civil rights movements fuelled the August 1965 Watts Rebellion. Thirty-four people were killed in the riots — most of them shot by the LAPD and National Guard — more than 1,000 people were injured, and more than 600 buildings were destroyed.

Despite the brutal police repression, the Watts Rebellion helped consolidate the Black Power movement and led to the emergence of the Black Panther Party in the late 1960s. It also engendered a period of cultural renewal known as the Watts Renaissance.

Davis and Weiner describe the Watts rebellion as a major turning point for Black activists, and as a rational and even strategic response to the racism and repression that Black people experienced.

From 1966 onwards, white counterculture and student activists also experienced LAPD brutality. The “Sunset Strip Riots” of late 1966 saw white youth in conflict with police. In June 1967, the LAPD attacked a 15,000-strong anti-Vietnam War protest outside the Central Plaza hotel where US president Lyndon B Johnson was speaking.

Between 1968 and 1970 LA’s radical movements were led by Chicano (Mexican-American) and African-American high school and college students who staged “Blowouts” (Student Walkouts) to protest racism and overcrowded and underfunded schools.

The Chicano movement culminated in August 1970 with the Chicano Moratorium — a massive rally against the Vietnam War that linked the struggle for Chicano rights with the anti-Vietnam War movement.

Women and LGBTIQ+ movements also flourished in LA the late 1960s and early '70s, with the earliest women’s activists in the city being Black single mothers on welfare.

Queer activists held the first legal Pride parade in 1970 after a successful struggle in the courts against prohibition by the LAPD.

The Asian-American movement also grew, with students at UCLA producing the Gidra newspaper (1969–74).

By 1973, however, LA’s radical movements had largely dissipated. They were depleted by sustained resistance and repression from reactionary forces such as the superconservative mayor and the LAPD under chief William H Parker, whose racist policies left a lasting legacy of police brutality in the city.

Moreover, Ronald Reagan, Republican Governor of California from 1967 to 1975, directly targeted activists and enforced greater police powers.

Set the Night on Fire places African-Americans, Chicanos and Asian-Americans, women and queer activists back in the centre of LA’s often whitewashed history. Links are also made to today’s progressive movements, which is important considering LA is still plagued by many of the same inequalities.