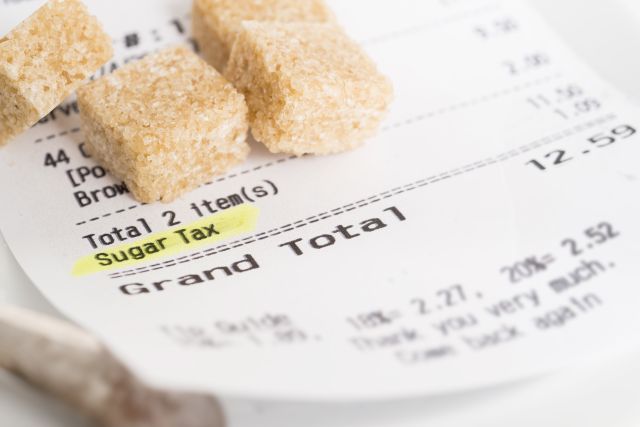

Australian Greens leader Richard Di Natale has pledged to introduce a private senator’s bill by the end of the year for a “sugar tax” which he estimates would claw $500 million from the country’s shopping list each year.

The legislation which Di Natale has hailed as an “obesity prevention strategy”, has raised ire among his own ranks who have labelled the policy a “captain’s call”.

The ABS reported in 2012 that 62.8% of Australian adults were overweight or obese. The health risks associated with obesity are undeniable, but research indicates that the success rate of the proposed sugar tax would be marginal, and that obesity would only fall by approximately 1%.

So why won’t the sugar tax work?

To contextualise the rise of obesity, we must understand the politics of food. In the 16th to 18th centuries, in an era of food scarcity, obesity was a symbol of wealth. So much so that prestigious “Fat Man’s Clubs” began springing up in the 1800s. Membership boasted status and power.

With the rise of overproduction in the early 20th century, food supplies became abundant and obesity became undesirable. The haves began consuming high quality healthy foods and the have-nots began consuming cheap packaged food, frozen food and highly processed fast food.

The last Fat Man’s Club called it quits in 1903.

The gluttony of today’s rich is not manifested the same way it was for bloated elites like Henry VIII. Now, the lower your income, the more likely you are to be overweight and vice versa.

The equation is simple: fast food chains have two dollar menus, but the cost of fresh, organic produce and a gym membership, and the free time required to prepare meals and work out, demands a more robust income.

It’s easy to see then, why taxing unhealthy food just doesn’t add up. Obesity is a symptom of the underlying problem: poverty. And you can’t tax people out of poverty.

The sugar tax would fall among an array of pre-existing “sin taxes” pushed by Labor and Coalition governments alike, like the levies on alcohol, tobacco and gambling, designed to stigmatise and disinsentivise the few pleasures of workers and the unemployed.

Meanwhile, wages are dropping and the qualifications for government entitlements become more and more exclusionary.

These discriminations echo historical inequities in the social safety net, which distinguish between the “worthy” and “unworthy” poor. The myth goes that there are a handful good, hard-working blokes who have fallen down on their luck, and then there are the lazy unemployed and underpaid masses that the system has failed.

Or as former Treasurer Joe Hockey described it, there are “lifters” and there are ”leaners”.

Characterisations of the “deserving poor” are a staple of Australia’s social security system which still linger today. The age pension under the 1908 Invalid and Old-age Pensions Act included a nebulous character test, rendering only those of “good character” eligible.

People who had not worked their whole life and thus were guilty of “habitual failure to work” were not eligible. Also excluded were single mothers, those in receipt of “poor relief”, “lunatics” held in asylums, persons sentenced to prison for 10 years after their release, and those convicted of “drunkenness”.

Racism also pervades the system. At the height of the “Yellow Peril”, Asians could not qualify for entitlements unless they had been born in Australia.

Section 137A of the Social Services Act 1959 said: “An Aboriginal native of Australia who follows a mode of life that is, in the opinion of the Director-General, nomadic or primitive, is not entitled to a pension, allowance, endowment or benefit.” Even when Aboriginal people were found to be eligible for pensions, they had to apply to the local police officer or magistrate to gain access to any of their entitlements and they could be denied them arbitrarily.

Today’s paternalism persists in the form of the racist “Basics Card”, first rolled out under the Northern Territory intervention, which quarantines between 50% and 70% of welfare payments, can only be used at government endorsed stores and then only for “necessities”.

These anti-poor policies fan the flames of middle class moralism that chastises the poor for being “sinful”, while romanticising the obscenely opulent lifestyles of the elites.

But, aside from being paternalistic and patronising, these measures do not work because punitive measures which make unhealthy items more expensive for the poor do not address the reasons people reach for them in the first place.

Raising the cost of sugary drinks cannot solve obesity, because it does not provide people with the means to eat healthier food. In reality, consumer taxes can only compound the rising cost of living, not raise the quality of life.

The real solution is to: make healthy food cheaper and more accessible; pump funding into health services and physical education and devote resources to local public gyms and aquatic centres that boost the health of their communities; raise wages and government entitlements to well above the poverty line; and reduce the working week to provide more jobs and more time to pursue a healthy life style.

Only a combination of these measures can begin to close the food gap and put healthy food within the reach of the poor.

Like the article? Subscribe to Green Left now! You can also like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.