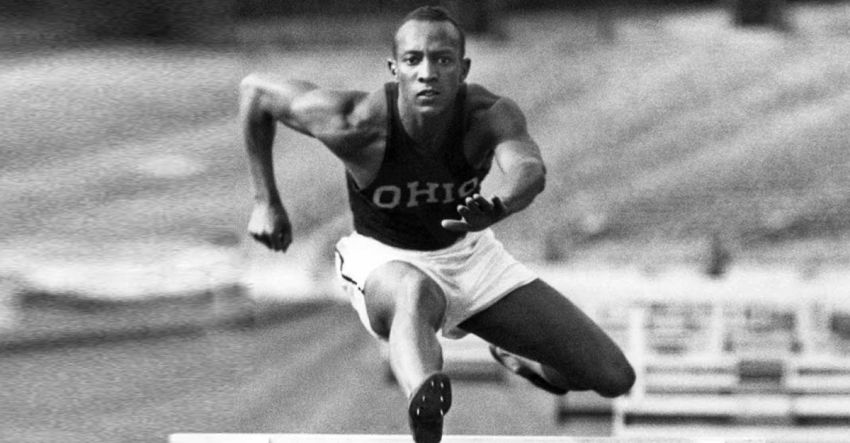

Triumph: Jesse Owens & Hitler’s Olympics

Jeremy Schaap

Head of Zeus, 2014

272 pages

He may have been the world’s greatest athlete at the time, writes Jeremy Schaap in Triumph, but Jesse Owens was also a Black American. Therefore Owens, the winner of four gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, was refused a room at hotel after hotel on his arrival back in New York, until a agreed on condition that he use the service entrance.

To the grandson of slaves, born into rural poverty in Alabama, racism was part of the deal. Picked up by Ohio State University as a track star, Owens could not live on the whites-only campus, was refused service in restaurants and coped with daily prejudice only through his outstanding ability to run and jump.

It is little surprise, then, that Owens did not support the movement to boycott the Nazi Olympics on the justifiable grounds that it was hypocritical for the US to oppose discrimination against Jews in Germany given its treatment of Blacks.

Financial self-interest also played a role in the decision of Owens (who faced a future as a petrol-station attendant) and other Black members of the US Olympic team in welcoming a trip to Berlin. Black Americans generally, however, were split on a boycott. Many argued that attending what Hitler planned as a spectacular pageant of Nazi grandeur and power would legitimise the concept of a “master race”.

Some Black Americans, however, argued that “Black Gold” (which was almost certain with Owens) would refute claims, Nazi and American, of white superiority. Hitler was duly embarrassed by the gold medals won by Owens and other Black Americans, pointedly leaving his box before the medal presentations and refusing to press black flesh in private receptions.

Also irked was president of the American Olympic Committee, Avery Brundage, the reactionary millionaire member of a whites-only club in Chicago, a “crypto-fascist” and future International Olympic Committee head.

Team USA wasn’t winning gold, Team Black was, and Brundage vindictively suspended a financially-strapped and physically tired Owens from any future athletics competitions, amateur or professional.

Owens, therefore, struggled financially, sometimes selling himself to race against horses. In the depths of the Cold War, however, Owens “found he was useful — to industry and government” as a symbol of the democratic opportunities that Washington liked to boast of when it compared itself to the Soviet Union.

The State Department sent an amenable anti-Soviet Owens on “goodwill” tours of Asia to promote his example of a poor outsider who made good in America, rather than making communist revolution in the poor world.

Unfortunately, Schaap’s writing, unlike Owens’ athleticism, doesn’t take flight. It is mired in sports journalism cliché and his treatment of Owens’ politics is cursory.