Protests against an attempt to stifle student participation in elections for representatives to faculty boards have triggered one of the most important student occupations seen in Central America in recent years.

The occupation, which began in August, has shut down Guatemala’s sole public university, the University of San Carlos (USC). It has become a direct challenge to the privatising agenda of successive governments and university administrations.

The USC has about 120,000 students and is a direct legacy of the progressive government of Jacobo Arbenz, who was overthrown in a CIA-organised coup in 1954.

Arbenz introduced many progressive reforms, including redistributing land to peasants and creating the USC.

The USC was created as an institution open to all society and dedicated to study and research for the benefit of the people.

To fulfil this mission, the university was granted autonomy from government and encouraged to use academic freedom to criticise governments and policies detrimental to the people.

However, as subsequent repressive regimes brutally put down insurgent movements and attempted to wind back the important gains of Arbenz’s “democratic revolution”, USC became a key target of their attacks.

Power cliques fought for control of the university as governments worked to undermine the quality of education and stifle dissent coming from USC.

So when university management moved to disqualify students from the Student Association for Autonomy (EPA) from being able to take part in faculty board elections, students saw the exclusion as a reflection of the broader policy of discrimination carried out by university authorities and the government.

Constitutionally 5% of the national budget must go to USC, but the government of Alvaro Colon has designated only 2.3%.

Meanwhile, in a country with 25% illiteracy, Guatemala has 11 private universities compared with just one that is public.

The use of entrance exams at the public university has meant only 20% of those seeking to enter the public tertiary education system are given the opportunity to enter USC. The large majority of these students come from private high schools.

Those rich enough to afford it can choose to pay exorbitant tuition fees at the private university, but those from poor families are locked out from obtaining a degree.

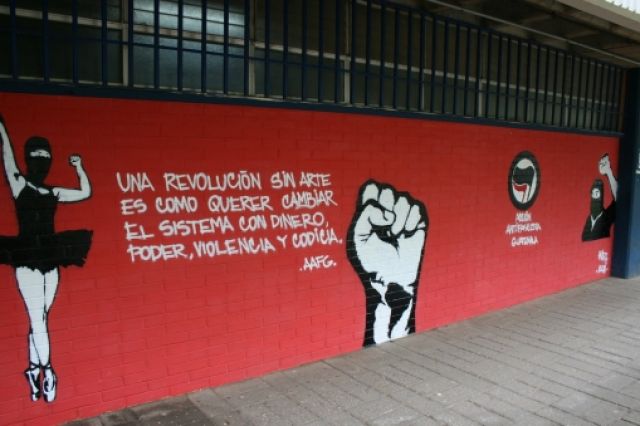

Activists have also raised university autonomy as another key demands, criticising how the USC has been converted from an institution for critical thinking into a factory for producing managers and entrepreneurs.

Through their actions, the students have turned USC into a vital space for critical discussion in Guatemalan society — exactly what the university was intended to be.

They are also raising the need for a congress to discuss university reform to return USC to its original objective.

The occupation has yet to reach the heights of the year-long shut down of the National Autonomy University of Mexico over 1999-2000. But it is an important break in the general passivity of student activism across Central American universities ravaged by decades of repression and neoliberalism.

University rector Estuardo Galvez has raised the prospects of regaining control of the university through force. This means solidarity with USC students and the extension of their struggle to other universities in the region is critical.