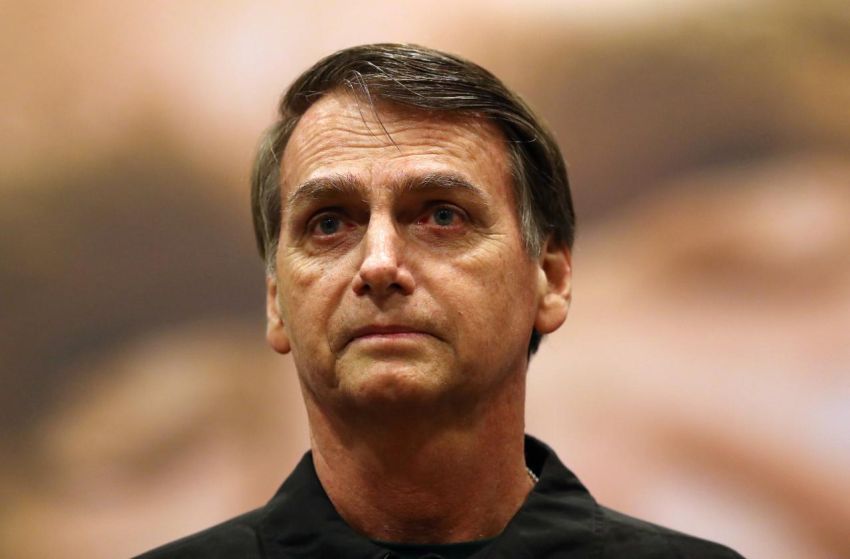

Recent cabinet changes and the simultaneous resignation of commanders of the three branches of the armed forces, all occurring amid a profound health crisis, have exposed the sharpening nature of the crisis within the bloc of power that has backed Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro since his election in 2018.

Bolsonaro’s COVID-19 denialism has been accompanied by generalised incompetence when it comes to managing the state. The latter has led sections of the elite to distance themselves from him.

“Many would prefer a Bolsonarismo without Bolsonaro”, explained Carta Capital editor Sergio Lirio, speaking with Pablo Stefanoni.

The fracturing of Bolsonarismo is also linked to the return of former Workers’ Party president Luiz Inácio "Lula" da Silva to politics, following the Supreme Court’s annulment of corruption convictions against him.

What is behind the crisis in the military and, in your opinion, how deep is it?

It is important to remember that the armed forces are one of the pillars of the Bolsonaro government, together with the financial and agribusiness sectors. This is the social coalition that was behind the coup against former Workers Party president Dilma Rousseff.

The expectation was that Bolsonaro would carry out an ultra-neoliberal agenda and restore the armed forces’ image, which had been eroded since the dictatorship.

Not even during the dictatorship did members of the armed forces occupy so many posts as under Bolsonaro. There are about 6000 members of the armed forces in numerous posts at different levels of his administration. In fact, the head of cabinet is someone from the military.

They preside over the state oil company, Petrobras, and Furnas, the largest electricity generator in Latin America. Even sons and daughters or wives of members of the armed forces occupy various positions in the state.

The military benefited from its own specific pension reform, which was much more favourable when compared to what the rest of the population received.

So the question is: why carry out a coup if Bolsonaro is already heading a militarised government? It would, moreover, be an adventure that would come with some extremely high costs.

The problem for the armed forces, as well as for the other sectors that threw in their lot with Bolsonaro, is that his government is a complete disaster.

The economy, under ultraliberal minister Paulo Guedes, is a calamity.

Even worse, when the pandemic hit, Bolsonaro came out, in a hyperbolic manner, against all social distancing measures. The results in terms of health indicators are so terrible that Brazil is now one of the countries with the highest death toll.

Furthermore, Brazilian foreign diplomacy has been an absolute failure; never before was it so ideologically-driven. With ultraconservative Ernesto Araújo as foreign minister, Brazil’s foreign policy was shaped by conspiracy theories, damaging international relations and trade.

Even though [former US president] Donald Trump was not a complete ally of Brazil, while he was in the White House he protected Bolsonaro, who was becoming a pariah on the international scene. This has changed, however, with the arrival of Joe Biden.

Now Brazil is seen as an international threat. More than 100 countries have prohibited entry to Brazilians. We have suffered more than 300,000 COVID-19 deaths, and could reach 500,000.

There is not only international opposition to Bolsonaro’s health policy; there is also opposition to his environmental policies, for example with regards to the Amazon.

Domestically, the emergency payments of BRL 600 a month approved by the Congress ensured the economy did not slump even more than it did during the first year of the pandemic (-4.1% in 2020), and that a greater tragedy was not inflicted on the people.

But now these payments are being halved. For all these reasons, Bolsonaro is losing support among the elites and the population.

It is in this context that he has tried to get the armed forces behind his authoritarian push. The phrase “there is no possibility of a coup” was repeated so often, everyone began to suspect the contrary.

Basically, the president wanted general Edson Leal Pujol to come out against the Supreme Court's decision to restore Lula’s political rights. For example, on March 28, Bolsonaro claimed that the armed forces are nationalists on the side of the people, by which he meant they were on his side.

Amid a health and administrative crisis — Brazil has had four health ministers in four years — he wanted the military to support him in enforcing a kind of state of emergency that would grant him more powers. But the armed forces said no — at least for now — and remained loyal to the constitution.

[Pujol, along with the two other leading military generals — Ilques Barbosa and Antonio Carlos Bermudez — then resigned on March 30 after Bolsonaro sacked his defence minister.]

The problem is, unlike countries such as Argentina where the crimes of the dictatorship were put on trial and the past was analysed and discussed, Brazil’s amnesty law granted impunity to perpetrators, and effectively generated a kind of equilibrium between the military and civilian powers.

That is why the armed forces end up being above the constitution, above the laws. This is the gravest problem facing Brazilian democracy.

Not long ago, an open letter criticising the Bolsonaro government and signed by members of the economic elite was published. How deep is the fracture between these sectors and the government?

That letter is very significant, because it was signed by various bankers, among them the two main shareholders of Itaú bank, and by various neoliberal economists.

There is a section of old-fashioned and historic business owners, largely benefiting from cheap labour, who continue to support Bolsonaro.

But the more dynamic industrial sectors want to have less and less to do with Bolsonaro. They would prefer a Bolsonarismo without Bolsonaro.

The government is so incompetent that it cannot even guarantee following through on its own planned reforms. For example, the pension reform, one of the few that has been approved, was passed only because then-president of the Chamber of Deputies, Rodrigo Maia, from the Demócratas party, ensured it did.

But others, such as the deepening of the labour reform approved during the Michel Temer government, or specifically the destruction of the social model installed by the 1988 constitution — which has never been really applied — remain pending.

On top of this, we have Bolsonaro’s calamitous administration. The neoliberal economic project is now immediately associated with his craziness, his incompetence and his authoritarianism.

Bolsonaro’s dysfunctional government has transformed Brazil into a hated country. Not only by Biden’s United States or China; but also Russia and India. Exports have suffered as a result.

That is why much of the elite are seeking out a centrist candidate, something that appears to be not so easy to achieve. They realise that Bolsonaro’s failures could open the door to a possible return of the left in 2022, and that is what they fear the most.

What has happened in the past few days has to do with this pressure.

Bolsonaro’s approval rating is hovering around 30%. He is no longer concerned with governing. His sole focus is avoiding impeachment and making it to 2022 with at least some chance of making it to the second round of the presidential elections.

How do you see the prospects for Lula’s candidature? Will he be able to maintain his support given the “Lula effect” generated by the annulment of convictions?

Much of what is occurring now is linked to the restoration of Lula’s political rights and his return to the political scene. The fact that judge Sérgio Moro was deemed to have been “partial” when condemning Lula in 2017 has generated a sensation among many people that Lula suffered an injustice.

Bolsonaro modified some of his attitudes regarding mask wearing and vaccines after the return of Lula, who is seeking to present himself as the anti-Bolsonaro. He even changed his health minister, general Eduardo Pazuello [to cardiologist Dr Marcelo Queiroga].

Lula’s return was triumphant, but his name continues to generate disapproval in large parts of the population, not just among the elite.

Many in the Workers Party (PT) try to minimise the anti-PT sentiment that exists. But in my opinion, Lula, as well as uniting the left, needs to reach out to broader sections of society.

An “Argentine solution” — seeking another candidate and running as vice-president, as Cristina Fernández de Kirchner did — does not seem likely. The ex-president has already made it clear he will be the candidate.

But the road ahead is a long one. There is a great need for reflection within the PT: for explanations, for conversations.

The image that has been constructed of the PT as a corrupt party has not been automatically wiped by Bolsonaro’s incompetence, even if it has led to the broad, widespread and simultaneous deterioration of so many spheres of society.

[A longer version of this interview was first published in Nueva Sociedad. Translation by Federico Fuentes.]