Arlene TextaQueen

textaqueen.com

When my wife and I were in the supermarket the other day, we got chatting to a kindly white stranger. After a few seconds, the woman asked my wife, "And how long have you been here?"

Shoba has spent 29 of her 36 years in Australia, but the question was still jarring. She is Tamil, but has been mistaken for being Aboriginal by Indigenous Australians. The mistake is not surprising, as scientists have found genetic and linguistic links between Tamils and the First Australians.

Shoba received frequent racist abuse at school in rural New South Wales, including having meat pies thrown at her to turn her uniform the same colour as her skin. "Whenever I've received racist abuse,” she says, “I've always thought, well, at least my family chose to come here. It must be so much worse for Aboriginal people."

A question like "And how long have you been here?" would certainly be so much worse if she were Aboriginal.

Such questions are tackled head-on by radical Australian-born Indian artist Arlene TextaQueen in her poem "In response to your question, 'Where Are You From?'"

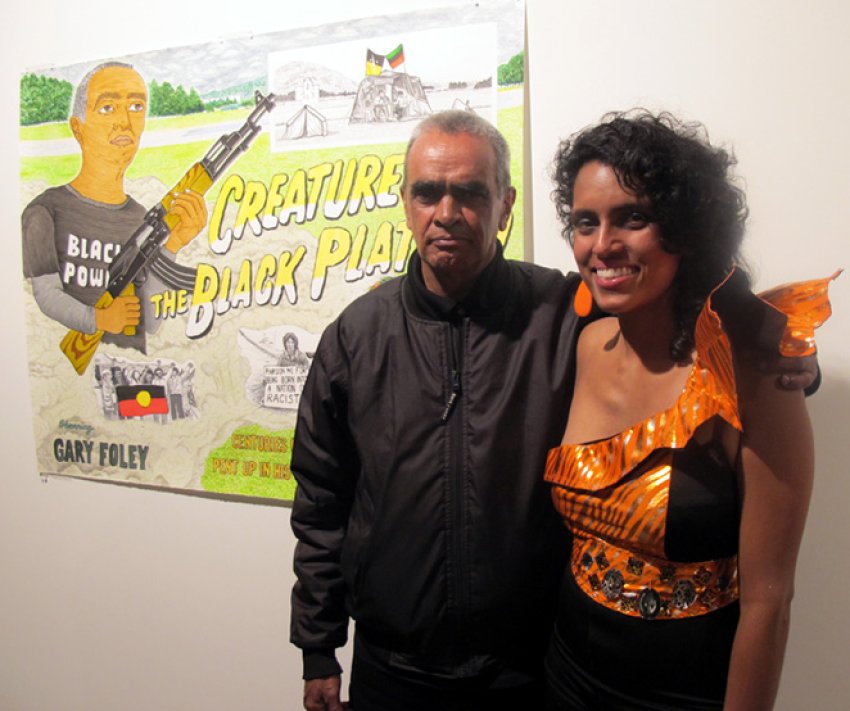

The self-styled superhero, who works only in felt-tip marker pen, recently showed her scathing poem to Aboriginal historian and activist Gary Foley as she drew his portrait for her latest exhibition.

"He asked me to guest, reciting it, for his Melbourne Festival show," she tells Green Left Weekly.

"It’s a poem about the invasiveness of that question, how it 'others' people of colour, and about the invisibility of whiteness. I was so flattered and nervous to perform it in the context of that amazing show.

“There seemed an uncomfortable audience response at the Foley show compared with when I read it at the RISE refugee poetry night a few months before, where it was met with laughter from the mostly people of colour audience."

That "uncomfortable audience response" was most likely the result of white people recognising themselves in the poem, their "invisible whiteness" suddenly exposed.

You might think that I, as the white husband of a Tamil woman and the father of our half-Tamil son, would know better, but TextaQueen's words apply equally to me.

Just the other week, when Pakistani activist-lawyer Sonia Qadir was introduced to me only as "Sonia", my first question was "Where are you from?" If I am honest, TextaQueen's poem seems to be speaking directly to the reasons why I asked.

"Why do you ask?

Is it your curiosity in the ‘origin of my features’?

Is it your fascination for ‘other cultures’ and what they have to offer you?

Why do you desire to establish an exact definition of my difference?

Why do you assume I desire to define this difference to you?

Do you show the same interest in determining the ethnic make-up of every white face that you see?

Is not everyone from somewhere?

Do you not have a heritage?

Why does whiteness make yours invisible but my brownness make mine subject to your anthropological investigation?"

When I later send the poem to Qadir, reminding her that it was the first question I asked her, she responds: "The poem's beautiful! I can relate to the feeling of being defined by your physicality! And it's very true what she says about the 'anthropological' interest in brown people. Like we were an abnormality."

TextaQueen experienced plenty of that feeling of abnormality as she grew up in the suburbs of Perth.

"I wasn’t at all a popular kid," she says. "Australia was possibly a more overtly racist place in the ’80s than it is today. I spent a lot of time reading in the library and lots of time alone. I can’t say I’d ever like to revisit my school days even though I loved to study. I’m really close to and grateful for the family I have; they’re loving and supportive. I was supposedly destined to be an engineer yet my Dad is my biggest art fan."

Her embrace of the marker pen was just as unexpected.

"I studied photography and video in my Bachelor of Fine Arts at university," she says. "And when I finished and I didn’t have a darkroom, video camera or edit suite — it was pre-digital days — I amped up my drawing output, first with Biro and then with markers. There’s much I love about the marker medium; that they’re ready to use, the childhood connection, they’re suited to contour line."

Her artworks are as vivid as her fierce poetry and fearsome intelligence. Their super-saturated colours jump off the page and pull the viewer in. TextaQueen limits herself to marker pen, but her creative use of her art is seemingly limitless.

She runs marker pen workshops for kids at which she turns up in full superhero regalia, caped and with her markers in a hip holster. She has blagged her way into concerts by doing portraits of the band, live.

She sells her artwork as posters, playing cards, postcards and stickers. She has built performances around them, showing them off at strip-poker evenings and in slideshow presentations where she talks about the people she has got to know as they have posed for her, naked.

From what she gets to know about her subjects, it would seem people open up when they pose nude in the same way as when a movie camera is trained on them.

"I think the camera ‘opens up’ people in a different way than being drawn," counters TextaQueen. "People often put on a persona to the camera and though they/we may have created a character for the portrait, drawing brings a different intimacy between the model and I.

“It’s not ‘unusual’ to me, it’s unusual if I don’t feel close to the person I’ve drawn after the process of drawing them.

"I’ve been drawing nudes for over a decade but my head’s not there right now."

Her latest drawing series, "We Don’t Need Another Hero" goes off in a typically original new direction.

"It’s pretty different than anything I’ve done before," she says. "I’ve asked people of colour to pose as outlaws of their post-apocalypse, drawn as fictional movie posters. The post-apocalyptic genre is used to discuss the experiences of Indigenous and other people of colour’s experiences of colonialism.

“This series has had more process, discussion, and design behind each piece than any other that I’ve created and it shows in the work. I’ve created a poster series of the drawings too.

“Cultural appropriation is so unchecked in Australia — that a Tiki bar can open in Melbourne in 2011 is outrageous. And it angers me how many bands and venues use imagery of people of colour in a way that’s other-ing, fetishising, and offensive.

"It’s been more satisfying to paste over these posters than to tear them down. I want to be part of people of colour representing ourselves rather than our cultures being appropriated and our representations being mediated by whiteness.”

So from where does TextaQueen draw her inspiration?

"[Aboriginal art collective] ProppaNOW are the most inspiring art collective of any sort,” she says. “Their works could speak for themselves, it’s art as activism, but the people themselves and their sense of community are just as inspiring.

"Annie Sprinkle was an influence for my pin-up playing cards. Her post-modern pin-ups were created in workshops with the models with a sense of collaboration and community that I admire and try to have in my art practice, and life.

“I think I’ve been more influenced and inspired by queer performance in Australia than any other artform. A lot of my subjects are queer performers from here and North America."

However, TextaQueen finds little inspiration in left-wing activism, and pulls no punches about it.

"I’m pretty disillusioned with white feminism and left-wing activism as I have known it in Oz," she says. "I’ve experienced and witnessed so much racism and sexism in white-dominated queer and radical circles; cultural appropriation of people of colour, resistance reduced to a ‘radical aesthetic’; racial fetishisation in the queer scene, especially of African American black culture; manarchist heroes leaving their white male privilege unchecked, white socialist solidarity with people of colour seeming to mean solubility with barely any critique of white privilege, ‘inclusion’ rather than empowerment.

“People thinking that all it takes to not be racist is to say ‘I’m not racist’ and being dismissive of any challenge to the anti-racist identity they’ve claimed.

"I’m much more interested in solidarity with other people of colour/queer people of colour for both personal empowerment and for that to be the basis in creating social change."

And if all that makes you feel confused or uncomfortable, it might just be something to do with what TextaQueen calls your “unexamined white privilege”. As my wife once said to me: "What would you know? You're white."

Below: "textanudes" and "Snap!" by Arlene TextaQueen.

Video: SNAP! textaqueen.