Searching for Sugarman

Directed by Malik Bendjelloul

Starring Rodriguez, Malik Bendjelloul

Music by Rodriguez

Now showing at selected cinemas

Director Mike Malik Bendjelloul’s film Searching for Sugarman, which has been nominated for best documentary film at this year’s Oscars and the British Film and Television Awards, traces the efforts of two South African fans to find out what happened to the mysterious Mexican-American folksinger known as Rodriguez.

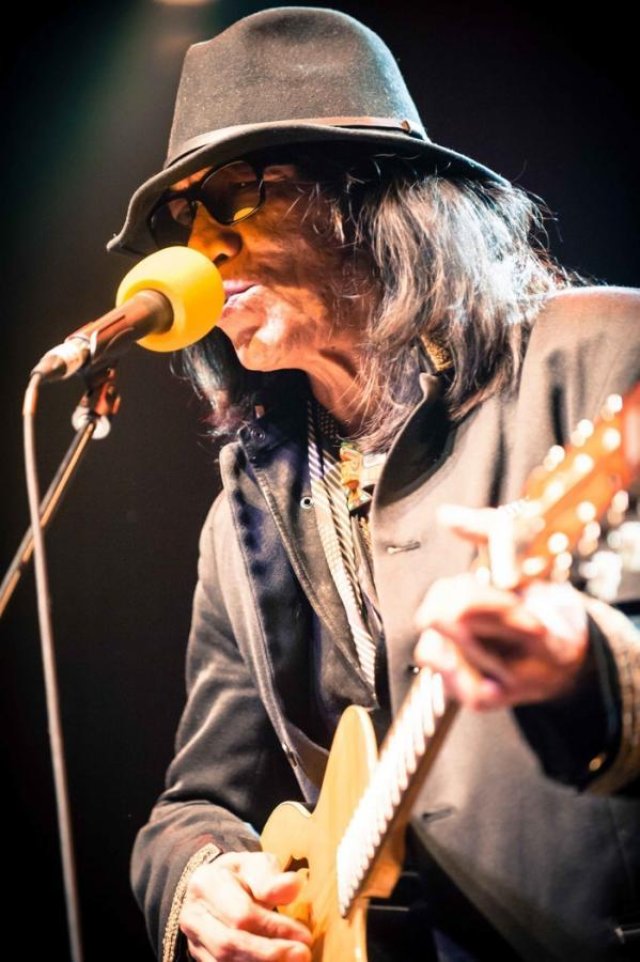

In 1968, record producer Dennis Coffey discovered Sixto Rodriguez, the son of Mexican immigrants who came to Detroit in the 1920s, playing in a bar with his back turned to the audience.

No one knew where the singer lived or what he did for a living. He was viewed as a wandering urban poet who documented the hard and gritty lives of working class people in Detroit’s poorest neighbourhoods.

In his 1970 song Sugarman, for instance, Rodriguez sang: “Sugar man, won't you hurry 'cos I’m tired of these scenes/For a blue coin won't you bring back all those colours to my dreams/Silver magic ships you carry Jumpers, coke, sweet Mary Jane.”

Compared to Bob Dylan as a singer-songwriter, Rodriguez was signed to the newly founded Sussex Records in 1969. The label was headed by former Motown chairman Clarence Avant, who said he considered the musician in the top five of the best musicians he had worked with.

That same year Rodriguez cut his first album -- Cold Fact, co-produced by Coffey and Mike Theodore. When the album was released in 1970, it gained favorable reviews but unfortunately didn’t sell in the United States. His 1971 follow up, Coming from Reality, also failed to sell and by the end of 1971 he was dropped from the Sussex label.

Producer Steve Rowland remembered the haunting premonition of this in Rodriguez’s song Cause: “Cause I lost my job two weeks before Christmas/And I talked to Jesus at the sewer/And the Pope said it was none of his God-damned business/While the rain drank champagne.”

However, in 1972, Cold Fact mysteriously found its way to Cape Town in South Africa and it caused a sensation among white Afrikaner youth opposed to the racist apartheid regime. Musician William Moeller remembers when he first heard the song I wonder, and how its mention of the word sex was a revelation in the ultra-conservative country.

In the song, Rodriguez sings: “I wonder how many times you've been had/And I wonder how many plans have gone bad/I wonder how many times you had sex/And I wonder do you know who'll be next.”

The heavy handedness and repressiveness of the apartheid regime weighed on the South African Broadcasting Corporation, whose archivist Ilse Archman remembers that the records of banned songs would be scratched so that they couldn’t be played on air.

Cold Fact was banned, but this only served to increase the cult status of the album. Various bootleg copies were made. Record store owner Stephen “Sugar” Sergman remembers that in the ’70s, if you went into the home of a liberal white family, you were bound to find three albums: The Beatles’ Abbey Road, Simon and Garfunkel’s Bridge over Troubled Water and Cold Fact.

In fact, Rodriguez was considered bigger than Elvis and the Rolling Stones in South Africa. When Cold Fact was released in South Africa, it went gold.

For musicians like Moeller, who were instrumental in forming the movement of anti-Apartheid Afrikaner musicians known as the Voerly movement in the 1980s, Cold Fact was the soundtrack and inspiration to their lives. It showed them it was OK to protest against their government, with songs such as Establishment Blues: “Garbage ain't collected, women ain't protected/Politicians using people, they've been abusing/The mafia's getting bigger, like pollution in the river/And you tell me that this is where it's at.”

After the end of the apartheid regime, Coming From Reality was released on CD for the first time in South Africa and gained gold record status. However, despite the fame Rodriguez had in South Africa, no one knew anything about the singer or what happened to him.

There were rumours of the singer committing suicide in various ways, including shooting himself on stage or setting himself alight. Sergeman and journalist Craig Bartholomew-Strydom set up a website called “The Great Rodriguez Hunt” in 1997.

This led them to find Rodriguez alive in Detroit. Eventually, Rodriguez’s eldest daughter Eva contacted Sergeman and soon afterwards he found Rodriguez living in the same rundown house he had been living in for years.

He had been unaware of his fame in South Africa for all those years, having laboured in obscurity doing various jobs and raising three daughters.

At the same time he supported various progressive and working-class causes and ran unsuccessfully for political office, and took his daughters to museums, art galleries and libraries. Eva said: “We have been poor, but that doesn’t mean our dreams were not rich and our souls not full.”

In March 1998, Rodriguez did his first tour of South Africa, playing six sold out concerts to crowds in scenes reminiscent of Beatlemania in the 1960s. Moeller’s band Big Sky provided backup. At the beginning of his first show, he thanked the crowd for “keeping him alive”.

He has played in South Africa four times since and recently has been asked to play at music festivals such as Glastonbury. Despite this recognition, Rodriguez continues to live simply in the same house in Detroit he has lived in since the early 1970s and has given most of the money he earns to family and friends.

On seeing this movie, I was glad to see that Rodriguez has finally started getting the recognition he has so long deserved. It is an extraordinary story definitely worth seeing.

[For more information visit the official Rodriguez website.]