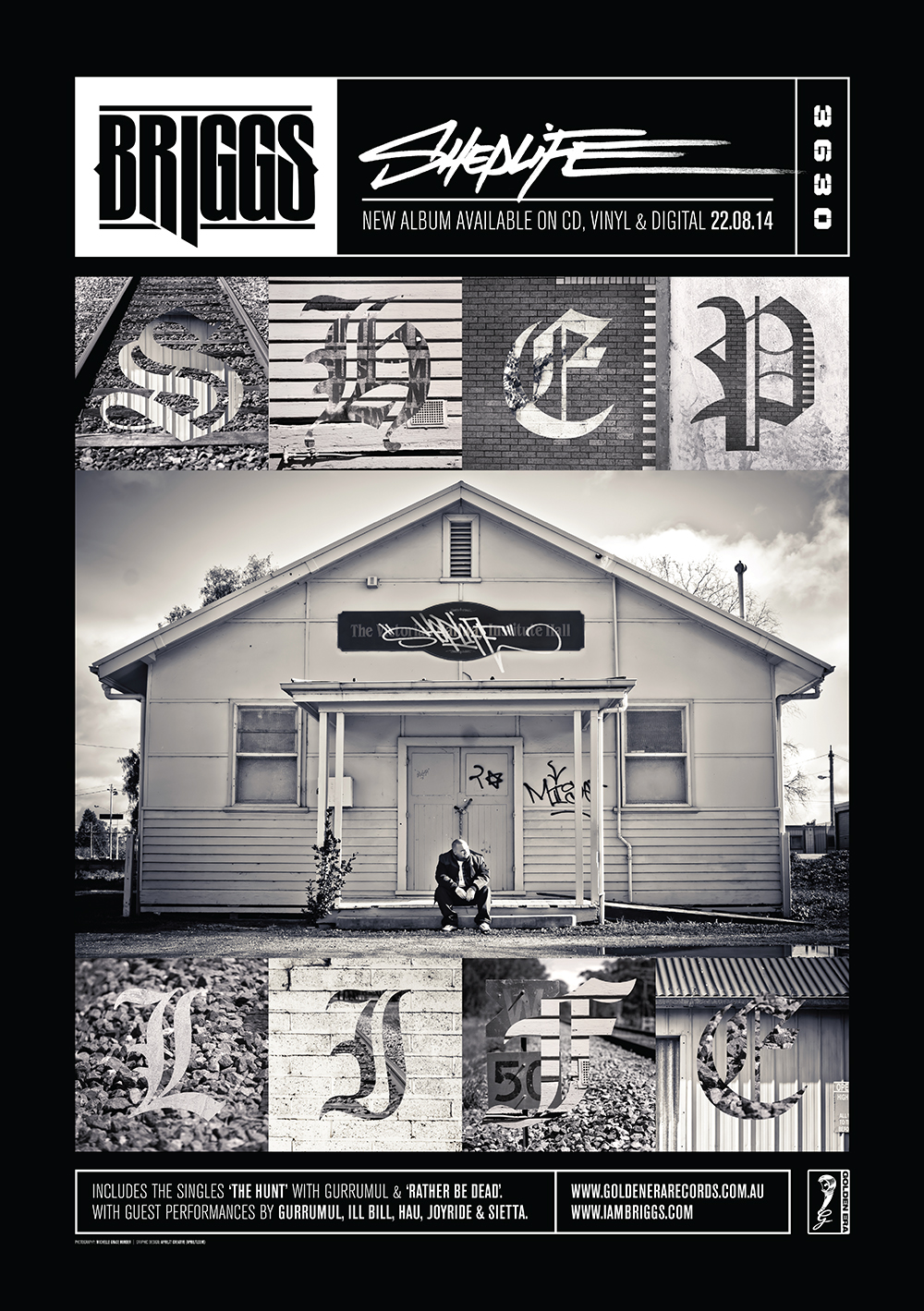

Sheplife

Briggs

Golden Era Records

Released August 2014

Now touring

www.iambriggs.com

Briggs is 598 kilometres from his hometown of Shepparton - and he's missing his bed.

"When I'm at home I don't have people ringing me up telling me I've got to get out of the house," says the rapper, sitting on his hotel room's balcony in Sydney.

"In a hotel you've got to check out and lie and bullshit. They're ringing me up and getting all the lies they hear every morning, like, 'Yep, I'm just in the shower! I'm just in the shower at the moment! I'm just doing this! I'm just doing that! Yep, I'll be down in five!' We all know what's happening - I'm just laying there."

Briggs, the biggest name in Aboriginal rap, grins. The sun beats down on the balcony and bounces off his Ray-Bans. A large stogie smoulders between his fingers.

In fact, Briggs' house is now in Melbourne's northern suburbs, to where he recently relocated. But his home will always be the much-maligned rural Victorian town of Shepparton - famed, as one socio-economic report puts it, for its "bogans, rednecks and criminals".

Briggs takes Shepparton with him wherever he goes. He's now half way through a national tour promoting his latest album, Sheplife, a homage to his hometown that rolls like the grittiest film noir. On his hotel room's sofa, his lean, shaven-headed cousin, Brad - from back home - is relaxing.

"I don't like going places that I can't take my cousins," says Briggs. "Everywhere I go I try to take someone with me who's my family, otherwise I get bored. Because I don't drink and I don't do drugs, partying and stuff doesn't really appeal to me. You've got other people who are stars and I just don't care about all that stuff, to be honest. It's just not interesting to me. I'd much rather be having a laugh with my cousin."

Briggs owes a lot to his cousins. It is they who sharpened the young Adam Briggs' tongue. It is they who honed Briggs' storytelling abilities. It is they, the Yorta Yorta people, who cared for their land for thousands of years before a stranger named Sherbourne Sheppard came and stamped his name on it, almost wiping out those stories for good. Briggs has his skills because when everyone's got yarning in their blood and you're trying to get a word in edgeways, you've got to be fast and you've got be funny.

"I was the youngest, the chubbiest, the favourite," says Briggs. "My nan's favourite - so I used to get it, man, on a regular basis. You had to be quick, man. If you weren't quick, they'd just gang up on you and you'd be done. You'd have to be quick to come back and cut it. You had to stop that onslaught before it got too hectic."

His comebacks impressed his cousins, but not his teachers. They didn't care that he came from a long, unbroken line of storytellers. They didn't care that his mother was a midwife, that his father was a community leader who was mentored by none other than the first Aboriginal person to be knighted, Sir Doug Nicholls, the governor of South Australia a decade before Briggs was born.

"I got told I wouldn't amount to shit," says Briggs. "Dead set. In primary school, I got told I would amount to nothing."

When Malcolm Little was told by his teacher that he could never be the lawyer he wanted to be, it awoke in him a lifelong anger that transformed him into political colossus Malcolm X.

When Adam Briggs was told by his teacher that he wouldn't amount to anything, it ignited a burning rage that transformed him into super-heavyweight rapper Briggs. A decade later, that anger exploded on his debut EP, Homemade Bombs, as he spat venom at his tormentor: "Fucking grade six, fucking 12 years old, I was told I'd amount to nothing - man, FUCK THAT."

The EP's look-at-me-now title track, "Homemade Bombs", was hurled in a wide arc that took out all Briggs' doubters.

Apparently we're getting everything for free

Where's this line for handouts? Cos this is news to me

Does that line exist? No it doesn't

Like you, the only thing we get for free is nothing

Except the stigma of being one of us

Which is second to none, nothing before, nothing to come

Coon, Abo, boong, nigger - pretend you never say it

Pretend you didn't laugh then, pretend you're not racist

And if you think that's about you, fucking maybe it is

But don't get mad at me about it - take a good fucking look at yourself

The notion that Aboriginal people get all kinds of handouts is an all too common misconception.

"That's one of the main ones, is like how Aboriginal folk get all this free shit," says Briggs. "It's just untrue. That's just not how it works. I used to get into fights over that shit. My dad had a work car and people would be like, 'Where did your dad get his work car from?' I'd be like, 'I don't know, the same place your fucking dad gets his work car! From his fucking job, cocksucker!'"

Briggs knows his family were lucky to even have a status symbol like a car. Just a kilometre from where Briggs now sits, Sydney's Western train line takes its passengers on a journey through Australian inequality. In the north, it stops at former state premier Barry O'Farrell's electoral seat of Wahroonga, where the ultra-rich show off their wealth through their huge houses, kept sparkling by house-washing servants. Out west, it stops at Mount Druitt, where the not-so-rich show off their wealth through their cars, parked proudly on the lawn. Such parking is a worldwide phenomenon, no different in Shepparton, about which Briggs raps on "Sheplife":

20 feet hose minus 16 bongs means you can only water about half of ya lawn

But it doesn't matter, that's what the parking's for

"Some people are selling their cars, some people are parking their cars and some people are just leaving them there," he says. "They've got to fucking mow around them. You can see how long the car's been for sale for by how high the fucking grass is. 'Nah, it's up to the fender!'"

US social critic Vance Packard notes in his book The Status Seekers how the poor are more likely to park their cars outside the garage than those who can afford more expensive homes.

"That's a rich man's dream, showing off your car," counters Briggs, glancing at his feet. "More like showing off your Jordans, you know what I mean?"

On his feet are a pair of his beloved Nike Jordans. Around his neck dangles a silver pendant shaped like the head of journalist and broadcaster George Negus. The pendant is a joke, but the chain has a deadly serious link. On his new song "Victory", Briggs links it to the neck chains that were placed on Aboriginal people by the settlers:

They put the chains on our necks, and we here so what’s next

I’m gettin' paid for shows and that payment shows in this chain around my neck

Video: BRIGGS x Dr G Yunupingu x Flume - Victory. Briggs.

In what Briggs calls "a $300 practical joke", Negus was chosen for the pendant just because his name "rhymes with Jesus". His "Negus chain" is a piss-take of the gaudy "Jesus chains" worn by US rappers in their oxymoronic displays of wealth and Christianity.

But Briggs' barbs aren't aimed solely stateside. After one of Australian Hip-Hop's biggest stars, 360, caused controversy by charging fans $1000 for a selfie with him in VIP package deals, Briggs downstaged him with his own Sheplife VIP packages. He announced that people who bought a ticket to his show could come to the soundcheck and get a "10 million dollar selfie" - for free. Those who paid an extra $5 could ride with him in a taxi to the show: "I call a cab but you at least gotta throw in a $5er on the night too, don't be cheap."

It's not easy to get an interview with the rapper, as other interviewers have said. But anyone looking at his social media outlets can see it's easy to meet him as a fan. He has his priorities in order.

"Just in case things do blow up I want to know who my fans are," says Briggs. "Because I see people down the front row who know songs word-for-word and that's crazy to me. I want to remember these people.

"I say, 'If you want to meet me, that's cool, but it's probably going to be a disappointing experience.'"

He laughs.

"I wouldn't say I'm, like, a super-shy person. But I think I'm definitely a little bit different from what people would expect. If I don't know you or don't know who you are, I'm definitely way more reserved than I am with my family, who I'm comfortable with, you know what I mean?"

It's true that away from the camera and the microphone, Briggs almost seems like another person, another shape. Gone is the intimidating man-mountain with the effortless, electrifying wit that jabs and thrusts like a cattle prod. In his place is a tall, but hardly intimidating, man. One who ponders questions rather than flinging them back in the face of the interlocutor with lightning-fast humour. One who calls himself "an introvert with an extrovert's career".

Hardcore fans got to see that other side when they bought the "final boss level" VIP package - a 45-minute bus tour of Shepparton, which included Briggs showing fans around his parents' house.

Such a move may have surprised Australia's most successful rapper, the record-breaking Iggy Azalea. When asked on a US radio show about the issues facing Aboriginal people in her country, she replied: "The thing about Aboriginal people and why I think it’s difficult for them is because they don’t believe you should live in an enclosed structure like a house, um, they sleep under the stars, it’s how they live."

In response, Briggs - whose public, razor sharp tongue cuts even his best friends down to size - tweeted at her: "Hey @IGGYAZALEA I live in a house, you fuckin idiot."

It's not a post-colonial practice. After the British declared Australia "Terra Nullius" - a land of no people - the settlers shot themselves in the foot by extensively documenting all the Aboriginal people's houses they came across as they explored the country.

But Azalea's ignorance is all the more shocking because she claims she is "part Aboriginal".

Reminded of that claim, Briggs laughs.

"What part? Not her brain! She's by no means any benchmark of intelligence and a spokesperson on the social climate and socio-economics out here."

The socio-economic statistics on Shepparton speak for themselves. In the past year, a 75% spike in commercial burglaries and big increases in assaults and thefts from cars led to a 15% jump in Shepparton's overall crime rate, more than five times the statewide increase. Only 5.1% of people have a tertiary education, compared with 15.2% state-wide. It has twice the state average of teenage mothers.

Or, as Briggs puts it on "Sheplife":

Put your house on the market, it's staying for sale

That's not a house, that's just a tent with some nails

Rocking oven mitts, all your stuff is hot to touch

Even the back of the truck was off the back of a truck

Father's Day? That's confusing as fuck

Don't know who your Dad is? Everyone else does

Video: Briggs - Sheplife. Briggs.

In 2012, Shepparton was one of only five communities nationwide to be selected for the roll-out of welfare quarantining. The policy was first brought in under the Northern Territory Emergency Response, which was instigated by a fabricated ABC Lateline story and required suspension of the Racial Discrimination Act.

The federal government's own research has shown welfare quarantining has failed. But in targeting Shepparton, then-Indigenous Affairs Minister Jenny Macklin pointed to its unemployment rate of 8.3 per cent, compared with a national rate of 5.1 per cent. Sceptics might point to its Aboriginal population of 3.7 per cent, compared with 2.5 per cent nationally. They also might point to the fact that if you've done wrong to people, an easy way to deal with it is to separate them off from society, divorce them from their land, destroy their culture, banish them to the fringes, dehumanise them - and then blame them for it.

"'Bad Apples' was about that," says Briggs of one of the grittiest songs on Sheplife. "'Bad Apples' was about kids who get displaced and separated from society, because that's where it all starts. It starts with them saying, 'These kids. What's wrong with these kids?' Well, why don't you stop pointing your fucking finger and start putting in some work and trying to help? Try and address what the issue is, the fact that they are disillusioned and are disengaged. Not from just school and not just from community, but from society itself and disengaged from themselves and disengaged from their identity."

On "Bad Apples", Briggs raps over a dust-dry, detuned guitar lick and tolling bell:

They say one bad apple can spoil a whole bunch

What if all you had was bad apples for lunch?

What if all you had was all you could touch?

And what if before you even had a dream you were crushed?

Video: Briggs - Bad Apples. Briggs.

He was frustrated that his fans didn't engage with its message.

"Some days, you catch me on a pretty mellow day, where I'm like, 'So be it, it's all right,'" he says. "And then other days, I'll be like, 'Fuck them!'"

Briggs' huge appeal comes not only from his rapping skills. It comes from his humour, his charisma and his music's irrepressible catchiness. For non-Aboriginal fans, it's far easier to engage with all those elements than to engage with his confronting political message. For non-Aboriginal Australians, to deal with the reality of Aboriginal Australia - from the brutal present all the way back to unceded land being seized under the legal fiction of "Terra Nullius" - is to question whether non-Aboriginal people belong in the country at all.

"When you have to address Aboriginal issues, you're addressing the displacement of land," says Briggs. "And when you're addressing the displacement of land, people get very fucking uptight, because they think that you're trying to take their house away from them. That's what the problem is. That's why it's unspoken. Because people don't want to deal with that reality, because displacement of land means money."

Whenever humans anywhere in the world are given cognitive choices, they will automatically choose the path of least cognitive resistance. Briggs knows that. But when he saw that disengagement being eclipsed by racism, it almost ended his music career, if not his life.

"It was the casual racism of, 'Oh Briggs is dope, Aussie rap is the best, not like this nigger shit.' That was the shit that was infuriating. It was like, 'I'd punch you in your face if you ever said that to me!' And I'm like, 'Who the fuck am I making music for?'"

On Sheplife's opening track, "Let It Be Known", he admits such comments had made him give up making music. It didn't help that he'd stopped drinking - after one friend died from it and another became seriously ill - and he no longer had that convenient emotional off-switch to fall back on.

Video: Briggs I Wish. Australian Aboriginal Hip Hop.

"I think after I quit booze it kind of snapped me into being very susceptible to anxiety and it pushed me into a very deep depression," says Briggs.

People with far more privilege behind them and far fewer demons to face would have ended up in rehab.

"There was no fancy rehab for me," says the rapper. "It was something that I wanted to do by myself. I had no intentions of putting anyone else through my stuff. It took a while. There was a couch and a whole lot of Simpsons."

On his left forearm is a tattoo of Krusty The Clown from TV series The Simpsons. It's one of many tatts that stretch right across his skin, not that he's particularly fond of them.

"I wish I didn't have any, to be honest," he says. "If I could get rid of them all easily, I would. Too much work and life's too short to be sitting around getting lasered."

One of Sheplife's darkest tracks, "Purgatory", references the tattoos on the back of his hands, the popular land rights protest chant: "Always was, always will be, Aboriginal land."

Always was, always will be

If I gotta stay here, you might as well kill me

"I was just looking at my hands when I was writing it, really," he says. "And I was just talking about where I was as a person at that point in time. I wasn't happy where I was and it was like, if I didn't change what I was doing and where I was and how I was feeling, I might as well be dead. It was like all my frustrations coming to a head."

It's often said that Aboriginal people have to work 10 times harder than others to get ahead in life. For Aboriginal musicians, it also seems like there are 10 times the issues to deal with once they get ahead.

"When you're successful as an Aboriginal person, you're automatically expected to adhere to a certain standard of role model, of leadership - be it if you're a sports star, a musician, an artist or whatever," says Briggs.

"There's a whole other level of responsibility that can be thrown upon you. And that's just another facet of being an Indigenous person of notoriety. There's also the ideas that you have to be able to juggle, being an artist and being an Indigenous artist.

"When I set out, I didn't want to be the best Aboriginal rapper. Nah, I wanted to be the best rapper, full stop. I don't wanna disrespect rap, I don't wanna disrespect my culture. I represent both in everything I do - hip-hop and my heritage and my family.

"Then, on top of that, people don't understand that for anything, being black, you have to overcome a struggle every day - in the sense of the everyday stuff of your health, of your mental health - that is disregarded."

That ability to survive against all the odds is addressed in "The Hunt", Briggs' collaboration with world-famous Yolngu musician Gurrumul. Briggs takes the superstar singer's totem, the crocodile, and crunches it down into its most primal elements.

We survived a death roll, death toll's something special

Here lies the best, put that on my head stone

Video: Briggs & Gurrumul - 'The Hunt' (live for Like A Version). triple j.

"The death roll is the crocodile move," says Briggs. "That's his killing move. In those two bars, what I'm actually saying is colonialism and genocide nearly wiped us all out, but we survived. Because the death toll was ridiculous. Not that people want to talk about it."

It might be said that Briggs and Gurrumul share similar ground in that they bridge the gap between the black and white worlds through their collaborations and their odds-beating popularity with mainstream audiences.

"We also bridge the gap between the north and south, ourselves," says Briggs. "You know, in the perspectives people hold of what a 'real Aboriginal' is, you know what I mean?"

Historian and activist Gary Foley notes how non-Aboriginal activists often travel to the north of Australia to work with "real" Aboriginal people, despite the fact most Aboriginal people live in cities.

"Yeah," says Briggs. "To get the 'real Aboriginal experience', you know what I mean? I work with just whoever I've got a relationship with. Gurrumul, me and him got along because we just both laughed at the same shit."

On their collaboration "The Hunt", Briggs also raps about a system totally at odds with the values of most First Nations people, "the system ain't broken, it's the way that it works".

"It's what I've always said," he explains. "The school system doesn't work for us, the jobs system doesn't work for us, the music system doesn't work for us, no system works for us - because that's the way that it works. People say the system's broken - nah, that's how it WORKS. It's not broken - it's fucking working perfectly, because we're getting fucked."

The death roll rolls on. On "Late Night Calls", Briggs addresses those phone calls that Aboriginal people, far more often than others, have to take.

Ain't funny how ya lookin' in ya phone

At the names and the numbers of the brothers that are gone

Press that button and you get the same tone

You can dial that number but ain't nobody home

It’s those late night calls that change everything

You don’t wanna answer, you just let it ring

Ain't no good news comin' from these phone calls

Ripped from ya sleep, and now ya can’t doze off

Feelin' like you miss a piece of your self

Thinkin' if they only knew how we all felt

It’s that feelin' you get, you’re missin a part of you

You lookin' at their face starin' back from an article

"'Late Night Calls' was about a cousin who got killed in a fight," says Briggs. "He got stabbed and I knew I was going to write about it, but I wasn't sure how I was going to deliver it. And then it was like it was meant to happen, because I got sent the beat from James from Sietta and then I was at the corner store and I'd seen this picture on the front of the newspaper and I went, 'Fuck.' That's when I got that line, looking at that face staring back from an article. That's when it clicked.

"You know, any given year, you'll go to, almost a funeral a month. It's no joke. And that's to do with a health situation, both mental and physical, and the kind of connection that you have with the community. It's not just immediate family that you have love and respect for. When I'm representing my people, it's not just my immediate blood. I represent a whole faction of people who are distant relatives, not even blood relatives, but they're still my family."

But in the sleeve notes to the Sheplife CD, Briggs emphasises that he doesn't "pretend to represent all the indigenous people across the land".

"That's just a disclaimer," he laughs. "Because that's dangerous territory. Because people forget that before settlement, we were hundreds and thousands of nations. I don't like to pretend. If I represent for you, cool. I'll take that on board and I'm with that. But if I don't, I never, ever said I did."

Briggs also contends that a CD is not a full representation of himself.

"If anyone wants to know what I'm about, they've got to come to a show," he says. "They're not going to get the full idea just from listening to my records. If they come to my show they see the full spectrum of what makes up my character that is Briggs, because Briggs is really Adam amplified to 1000."

That night, when Briggs steps onto the stage, the man-mountain is back, amped up to the max and making the audience eat hungrily out of his hand. It's a stand-up comedy routine and banging hip-hop show rolled effortlessly into one. When he raises an eyebrow, the crowd collapse laughing. When the beat kicks in, he blows the roof off. Briggs' house may be in Melbourne and his homeland may be Shepparton. But there, up on stage, is his true home.

Video: Briggs - Rather Be Dead (Official Video). Briggs.

Interview transcript

Below is the full interview transcript in which Briggs talks about Rolf Harris, Andrew Bolt, meeting George Negus and Ray Martin, the record label Briggs plans to start featuring his friend Djarmbi Supreme, plus much more.

* * *

So first of all I saw on Twitter the other day you were homesick from staying in hotels all the time - do you miss being in Shepparton?

I miss my bed! Not being in Shep! [Laughs] There's a difference.

So where've you been on this tour so far that's different? Any new places?

The Sunny [Sunshine] Coast. I've never been to the Sunny Coast. I've been everywhere. This is, like, the last leg, now. And then I've got, like, a group of shows that are tacked on at the end.

So how does the Sunny Coast compare with Shepparton?

It's weird, man, you don't really get to experience much when you're on tour, because it's like fly in, hotel, soundcheck, hotel, show, hotel, airport. You see lots of airports and lots of hotels. You don't really get to experience much else.

I can see why you'd get sick of it.

I don't really get sick of it - I don't get good sleep when I'm in hotels. Just because I'm not in my own bed.

So you miss Shepparton for all its faults?

I miss my bed.

What's so special about it?

No, it's like, when I'm at home I don't have people ringing me up telling me I've got to get out of the house. In a hotel you've got to check out and lie and BS, they're ringing me up and getting all the lies they hear every morning. You know what I mean? All those lies that they hear? Like, 'Yep, I'm just in the shower, I'm just in the shower at the moment! I'm just doing this, I'm just doing that. Yep I'll be down in five.' We all know what's happening - I'm just laying there.

Tell us about your childhood, who your parents were and what they did.

Mum was, like, a midwife and ran a birthing program for all the Koori girls in Shep. She did that for a good 15 years, something like that. And dad was the president of the footy club and used that to create a number of different, like, programs and offshoots and opportunities for the community and stuff.

What's your dad's name?

Paul Briggs.

The name Briggs crops up in conjunction a lot with the Yorta Yorta nation, right?

Correct.

Tony Briggs - actor, Sapphires writer.

Yep - that's my cousin.

Carolyn Briggs - Indigenous language specialist.

Yep, she had a restaurant as well.

Do you want to tell us about your other family connections, like Doug Nicholls and so on?

Well, Sir Doug Nicholls was, like, my dad's mentor. Uncle Doug was dad's mentor. He showed dad the ropes, you know what I mean? He was the governor of South Australia, he was a pastor and all that business, unheard of stuff for the times. Extraordinary feats. He was the one who showed dad the ropes. He was a footballer. Dad was a footballer, he was a runner. Hey Brad! [Briggs' cousin, Brad, is with him, lying on the hotel room couch. We're on the balcony.] Uncle Doug Nicholls - did he win the Stall Gift? Dad ran in it, but did he win it? I can't remember if I'm romanticising it, pretty much, or not. Some blackfella won it. Was it him? He might have won it, you can double-check that. [Laughs.] A different one? Not the Stall one? Every gift - gifted!

And tell us about your folks with the Cummeragunja walk-off.

Well, that was much before my folks. What year was the walk-off, Brad? Dad was born in '54 or whatever. It was before that. I forget, because all the information that we get is passed around and sometimes we don't take it all in. It's not that it's not important to us to know, but dates and all the rest of it...

Sure, I'd be the same if you asked me about my family, you know. What about Lieutenant Briggs, is that a connection? He was one of the first pastoralists in Victoria.

I don't know that one. Our name Briggs, we stole it, I think. Someone got adopted somewhere along the line, because we were all, like, Briggs-McCrae... [To Brad:] 1939 was the walk-off? Yeah, Briggs were like McCrae-Briggs and then someone assumed the name Briggs and then it went from there. They were McCraes and moved in with this Briggs family, something like that.

So one of my favourite quotes from you was from an [ABC radio] Awaye interview. You have a razor sharp tongue that cuts even your best mates down to size - like [music producer] Jaytee in the podcast - but you were saying in the Awaye interview your sharp tongue comes from having a lot of cousins, so you had to stick up for yourself.

Yeah well, I was the youngest, you know what I mean? I was the youngest, the chubbiest, the favourite - my nan's favourite - so I used to get it, man, on a regular basis. So being quick, that was just part of it - you had to be quick, man. If you weren't quick, they'd just gang up on you and you'd be done. You'd have to be quick to come back and cut it. You had to stop that onslaught before it got too hectic.

So you owe it all to your cousins?

Pretty much, man. My brother... [Pauses as people come out onto the balcony next door].

They've come out to listen in. So how many brothers have you got?

I've got two brothers, two sisters.

And you were the youngest?

Yep.

What are they doing now?

One's a teacher, two are mums and one's just recently got back into work - she works for the Yorta Yorta nation. And my other brother - he's a lawyer.

Oh yeah, I've read you talking about that.

Yeah. I don't need him, yet.

Talking of cutting people down to size, Iggy Azalea. [Briggs tweeted at her after she suggested Aboriginal people don't like to live in houses, that they like to 'sleep under the stars'.] I don't know if she even read it...

She might have done...

But [you tweeted at her], "Hey @IGGYAZALEA I live in a house, you fuckin idiot."

[Laughs]

Do you want to talk about that?

Well, Sway of Sway and Tech, had asked her about what was going on with the black man in Australia. Why he asked her, I have no idea.

Well, she claims to be "part" Aboriginal, as she puts it.

What part?

[Laughs] Not her tongue!

Not her brain! Erm, so then like, you know, she goes... At first she was like, how,... You know, I was kind of like, OK, she's going somewhere. She was like talking about how, you know, how blackfellas are mistreated in the country, blah blah blah. Then she starts to go on about how it's like because of their culture, they don't like to live in houses. You stupid....!

For me it brought to mind Aboriginal author Bruce Pascoe's book Dark Emu, because he goes through all the settlers' accounts of Australia when it was first 'settled' and they shot themselves in the foot because they described all the houses that they came across, that Aboriginal people had built. So, you know, there's a whole lot of ignorance around that issue.

She's just not the person...

To ask about anything!

Why the fuck would you?

That's why she's big, though!

Why the fuck would you ask Iggy Azalea about anything other than what the fuck she's wearing, you know what I mean?

But that's why she's so popular, I reckon.

But that's what I mean, like, she's by no means any benchmark of intelligence and - you know - a spokesperson on the social climate and socio-economics out here, you know what I mean? But that could have been anyone, you know what I mean? I'll take a shot at anyone. You know what I mean? Bless her.

Yeah, it was the same with [Rupert Murdoch columnist] Andrew Bolt when he said he had to take a day off work because he was so upset at being called a racist...

Aw bless him! Yeah, and then he started going in on Djarmbi! [Bolt attacked Briggs' friend, Quandamooka rapper Djarmbi Supreme, after he rapped that he was going to spear Bolt in the leg to show him light-skinned mob still practise culture.]

That's right!

He started going in on Djarmbi and I've been calling him a cunt for years! And then he starts on the brothaboy. You know what I mean? I'm like, agh, Djarmbi gets all the special attention.

He had to pick on the little man, that's why.

Yeah! See, cos he knows I'll catch him! [Laughs.]

I reckon. Yeah, what Djarmbi said your response was, when you heard about him taking a day off sick after being called racist, was, 'Stop saying racist shit then, ya dumb dawg!' [Briggs bursts out laughing.] And Djarmbi told me to ask you 'about Dumb Dawg Music Group'.

[Laughs] Yeah, it's just a fun little thing, Dumb Dawg Music, man. I'm always into creating, building, you know what I mean? Dumb Dawg Music is just gonna be something where we put out a few mixtapes here and there and stuff like that, another creative outlet that isn't based around making records and my serious stuff. Dumb Dawg Music is going to be ignorant, dumb shit.

Dumb rap?

Yeah, pretty much.

So is Djarmbi going to be...

Djarmbi's the poster child!

That's why he's asked me to ask you about it!

He's the franchise player of Dumb Dawg Music.

Let's move on from that, it's just a plug for Djarmbi isn't it?

Hmmm, that's why he said it, because he's the fucking poster boy.

So, your battle with drink - are you bored of talking about that?

Nah, I got bored of drinking. It wasn't a battle, because I won. But...

Yeah... It's not an easy thing to do, to give it up.

Hmmm.

But you did it all by yourself?

Yeah, there was no fancy rehab for me. There was a couch and a whole lot of Simpsons. And it was something that I wanted to do by myself as well. I had no intentions of putting anyone else through my stuff. It took a while.

And what made you decide?

Ah well, one of my good mates died, another one of my good mates got real sick.

From drinking?

Pretty much, that was the catalyst. And then, like, you know, I really just got bored of it. I was drinking so much, I'd been drinking since I was 16 or something, you know what I mean? It started to annoy me. The whole idea of that - this whole drinking culture in Australia started to annoy me. I was not really apprehensive towards it, I just hated it. I hated it! I hated the idea of, like, I just got to this point where I went, 'How come everything we do revolves around, you know, getting smashed?' I was talking to - I sent a message on Twitter the other day, and one of the dudes on that, Fraksha [a rapper signed to Broken Tooth Entertainment] said, you know, parents and people need to stop complaining about Halloween.

Yeah, I saw that one.

You know, they're all quick to jump on St Paddy's Day and Oktoberfest, because they revolve around getting pissed and smashed. Whereas Halloween, this is another thing for the kids, you know what I mean? It doesn't revolve around them getting pissed up with their mates. They have to be proactive with their kids and do something out of their comfort zone for their kids. So that's why it turns into this, 'Agh, it's American bullshit.' You know, blah, blah, blah.

Could well be, yeah. Could well be.

Oktoberfest isn't exactly Australian. Neither is St Paddy's Day. Yet you all wear your green hats and get your fucking lederhosen out.

There's also a lot of misconceptions in Australia about Aboriginal people drinking more than whites.

Yeah, that's not real. White people drink more than us and there's more of them to drink.

Yeah, well, that's exactly what the government's own statistics show, yet [former Prime Minister] Julia Gillard comes out with all this shit in her Closing The Gap speeches about Aboriginal people needing to stop their drinking and so on. It's all pretty cynical.

Hmmm.

So tell us about [your track] 'Let It Be Known' and racism - and you thinking about giving up music.

Erm, 'Let It Be Known' was, like, you know, that was the return of me back to where I was at, you know what I mean? Back to making tunes because I wanted to make tunes, you know what I mean? And the whole racism thing, it wasn't like I felt directly said against, you know what I mean? I never really felt that way. It was the casual racism of, 'Oh Briggs is dope, Aussie rap is the best, not like this nigga shit.' It was like, 'I'd punch you in your face if you ever said that to me!' You know what I mean? [Laughs.] Like, you know what I mean? That sort of shit. And I'm like, 'Who the fuck am I making music for?' You know what I mean?

That's what your fans were saying?

Yeah! Well, not necessarily my fans, but, like, punters - you know what I mean - what I'd see on comments and blah, blah, blah.

On other people's pages then?

Yeah! Oh, like, I'd rarely get it on my page. Not that casual racism like that. But that was the shit that was, like, infuriating.

So you just started questioning the sort of people...

Well, it was like, 'OK, who am I making music for?'

Yeah.

So, 'All right, well, if I stop making music for these people, who am I making music for?' And I got it all twisted, because I was thinking about other people, when I should have been thinking about why I'd done it in the first place, which is that this is what I do.

Yeah, sure.

Some people are carpenters, some people are mechanics, you know what I mean - I make music.

Yeah, yeah.

And so I got back to making tunes because that's what I do... I can fucking smell that barbecue man! [From next door.]

Am I keeping you from eating?

Nah. These cunts here next door are having a barbecue. Can't you smell it? Are you vegetarian?

No, I'm not vegetarian, but I just ate a big bag of snakes [confectionery] before I got here, so I'm not hungry.

I just had a fucking - what did we have - half a chicken! And then, they cook that! Barbecues make me weak, every time.

So, hey, you're like one of the most well-known and successful rappers in Australia. But you still have trouble getting by, right? It's not like you're mega-rich? It's not easy for artists - even for someone who works as hard as you.

Nah, no, no, no, no, no. People perceive that I'm, like, ballin' out of control or whatever, I smoke cigars. But like this cigar [holds up cigar], this is one of the cheaper ones that they had at the tobacconist that I walked by. It's not a bad cigar - it's like 25 bucks. So I buy this. But this is all I do.

It's your only vice.

I don't drink, I don't do drugs, this is the only thing I've got. This and coconut water.

So tell us about the reality of being a successful artist in Australia today.

Sacrifice, man. That's what you've got to do, sacrifice. You sacrifice, you sacrifice everything, you know what I mean? It's like all the shit that you... You know, you miss birthdays, you miss engagements, you know what I mean? You miss out on a lot, just to do this. You know what I mean? Especially in the earlier stages, when you can't afford - like, now I'm in a position where - it's not to say I can afford to knock whatever I want back, but I can do, 'Nah, not this time. I can't do that show.' Now I've got my...

ANZ Stadium? No thanks.

You know what I mean? You know, people would be surprised about the stuff that I've knocked back. You know what I mean? They're like, 'Why?' It just wasn't the right time, the right place, you know what I mean? Sometimes you've just got to feed your soul, man, and not your fucking bank.

Sure. So you talk about not being your average 'cookie-cutter rapper' and that's always been your sort of thing, right?

Yeah. Well, not out HERE, you know what I mean? I'm not your average rapper out HERE. You know, rap out here was predominantly white, in Australia.

Sure.

But it is what it is, you know what I mean? I've met a lot of good people, rapping out here. I've met a lot of great friends, you know, from all kinds of different backgrounds and different races, you know what I mean? And my style, again, was different to theirs, but we had a mutual respect, because, you know, the stuff that we did agree upon was the important shit, you know what I mean? Like [the rap group] the Gravediggaz.

Sure, OK. And you're a big fan of rap music - an unashamed fan of rap music.

I LOVE rap music.

As opposed to hip-hop?

I LOVE rap music. I love 50 Cent. I love fucking DJ Mustard and I love Young Jeezy and I love... I just love rap music, man. I'm not a purist at any... I can appreciate the purists, but I'm not a rap purist, you know what I mean? I'm not a Gucci Mane mixtape-copping fucking dude, you know what I mean? I like stuff I can play in my car.

An interesting thing you say in your latest CD's inlay is that you don't claim to represent all Aboriginal people. Do you want to talk a little bit about that?

That's just a disclaimer! [Laughs.] You know what I mean? Because, like, that's dangerous territory. Because people forget that before settlement, we were hundreds and thousands of nations, you know what I mean?

Yeah.

So, to say that I'm the same as the brotherman from north Queensland is not, you know - NOW it's more close, because of the conditions that we've been subjected to, but I don't like to like pretend, like, if I represent for you, cool. I'll take that on board and I'm with that. But if I don't, I never, ever said I did. You know what I mean? I never said I did. But if I do, then cool. You know what I mean? I'll be that spokesperson for you, if that's what you need. If you need that spokesperson, I can be that. If I, you know, yada, yada. If I'm not, then so be it. I'm not out here to make friends, you know what I mean? I've got enough...

It's for the people to choose you, rather than the other way round.

Yeah, it's a voting system, you know what I mean? We live in a democracy!

Yeah. [Laughs.] Yeah. So, you were talking about how your followers don't really engage with what you're trying to address in [your song] 'Bad Apples'. You've said you find it a bit strange how your fans don't engage when you get more political.

Yeah, I think a lot of the time, it's like with a lot of different things, is people forget and they lose sight and they lose the message in the track in a song because they're lost in a moment of THEIRS, you know what I mean? Whether it's them just vibing to it, or, you know, them getting their own interpretation of what it's about. So, you know, part of me says, you know, 'You should be feeling this.' But the other part of me says, you know, 'You put your music out there to be interpreted. You know what I mean? People are going to interpret it the way they're going to interpret it.' So, part of me is like, 'No, I'm saying THIS.' But then, sometimes I have to, you know, let people take what they are going to take, you know, out of the joint. I know what I said and I can't school everyone and I can't sit every person down and check, you know what I mean? I'd hoped that the film clip was going to deliver a bit more directly about what I was on about, you know what I mean. But, yeah, some days, you catch me on a pretty mellow day, you know what I mean, where I'm like, 'So be it, it's all right.' And then other days, I'll be like, 'Fuck them!' [Laughs.]

I'll tell you what it got me thinking about is, I think for any white people here in Australia to face up to the true history of this country and to know it and to know Aboriginal people and address those issues [entails] a whole lot of cognitive dissonance. [Psychologist Leon Festinger's theory of cognitive dissonance focuses on how humans strive for internal consistency. When inconsistency - dissonance - is experienced, individuals tend to become psychologically uncomfortable and are motivated to attempt to reduce this dissonance, as well as actively avoiding situations and information which are likely to increase it.]

Well, there's a problem, because when you have to address Aboriginal issues, you're addressing the displacement of land and when you're addressing the displacement of land, people get very fucking uptight, because they think that you're trying to take their house away from them. You know what I mean? But that's what the problem is. That's why it's such a... It's such a... You know, it's unspoken. Because people don't want to deal with that reality, because displacement of land means money. You know what I mean?

It also means facing up to the reality of what you've done and what your people have done.

Yeah. But, like, the reality is, is that, like, an argument that you'll hear often is, 'I didn't do that. Someone else did that. Why should I have to pay for that?' You know what I mean? It's like, 'We're STILL paying for it. Why should we STILL pay for it?'

In my opinion, that's why Aboriginal people are so dehumanised, it's just so that the colonists can deal with it.

Yeah.

To make them not real people...

That's how you separate it. And 'Bad Apples' was about THAT. 'Bad Apples' was about kids who get, you know, displaced and separated from society, because that's where it all starts. It starts with them saying, 'These kids, these kids. What's wrong with these kids?' Well, why don't you stop pointing your fucking finger and start putting in some work and trying to help? You know what I mean? Try and address what the issue is, the fact that they are disillusioned and are disengaged. Not from just school and not just from community, but from society itself and disengaged from themselves and disengaged from their identity.

Yeah. So... you've said about Sheplife being about as real as you ever get.

Hmmm, well as real as I've been so far, yeah.

But it's not like you eased your way in, you sort of kicked the door down with [your first EP,] Homemade Bombs.

Yeah.

It's not like you eased your way in and now you're suddenly hitting people over the head. So did you feel you stepped back a little bit with [your last album,] The Blacklist?

No, I feel like The Blacklist was like a souped-up version of my EP, pretty much. The Blacklist was like a group of songs that I just had, whereas Sheplife had way more direction, it had way more thought. It was way more a piece of art and an album that I put together, from the artwork down to how far apart the songs are mixed and the separation, you know what I mean, of just the dead air on the tracks. So that's what I mean in the sense of like...

That's as real as you get.

Well, yeah, so this is as honest as I've ever been throughout a whole piece of work, you know what I mean? You pretty much see every facet of my, erm... of my, erm... of my, erm, person, you know what I mean?

Yeah. So [Yolngu singing star] Gurrumul - he loves Elvis, Cliff Richard, Iron Maiden, Dire Straits - and you.

Yep.

You're up there with the greats.

Yeah, man. Dire Straits, he loves Dire Straits!

I just read the book about him, yeah! I reckon it's because you're so catchy as well. [Gurrumul's friend and music partner Michael Hohnen told Triple J Radio that Gurrumul was always listening to Briggs' music.]

I hope so. [Laughs.]

Yeah, I think that explains your popularity, the fact you're...

Well, me and him got on on a personal level, you know what I mean?

Right.

That was the biggest - like, Gurrumul, erm, me and him got along because we just both laughed at the same shit.

Right! And when you did 'The Children Came Back', the construction of the track was very like the construction of Gurrumul's 'Gurrumul History' - naming all your forebears or ancestors.

Yeah, well, I went through it. The first verse is like national heroes that people would know. The second verse is like historical heroes and the third verse is like my personal heroes, my dad and my uncles, you know what I mean?

Yeah, yeah, sure.

So that's how I went through it. It's like a tier, you know what I mean? I talk about Adam Goodes and Patty Mills. I talk about Lionel Rose and erm, you know, erm, Uncle William Cooper and then I talk about, erm, my dad and Cummera [the Cummeragunja mission walk-off], you know what I mean?

I wanted to ask you about a line from Homemade Bombs: 'Apparently we're getting everything for free. Where's this line for handouts? Cos this is news to me.'

Hmmm-hmmm.

It's a common misconception isn't it? Do you want to expand on that a little bit?

Well, it's like - that's one of the main ones, is like how Aboriginal folk get all this free shit, you know what I mean? It's just untrue. That's just not how it works. And erm, that was it! [Laughs.] I used to get into fights over that shit. My dad had a work car and people would be like, 'Where did your dad get his work car from?' I'd be like, 'I don't know, the same place your fucking dad gets his work car!' You know what I mean? 'From his fucking job, cocksucker!' [Laughs.] You know what I mean?

And tell us the line about your teacher saying you'd never amount to much. 'Fucking grade six, fucking 12 years old, I was told I'd amount to nothing.'

That was primary school. I got told I wouldn't amount to shit. Dead set. In primary school, I got told I wouldn't amount to nothing.

And did other mates get told that?

Nah, not really. I never heard anyone else get told that, just me. They might have told one of my other mates, but he really didn't amount to shit, so they were right! [Laughs.] You know, they're like one for two on that. If they were taking bets, they wouldn't be doing so bad. [Laughs]

I love the line from Sheplife: '20 feet hose minus 16 bongs means you can only water about half of ya lawn, but it doesn't matter, that's what the parking's for.'

[Laughs.] That's nan's house. [Laughs.]

She parks her car on the lawn?

Nah, nan just had a little hose, because cunts would be cutting it off and shit.

But that's what you're getting at - is that people would be showing off their cars on their lawn, right?

Yeah! [Laughs.] Well some people are selling their cars, some people are parking their cars and some people are just leaving them there - they've got to fucking mow around them. You can see how long the car's been for sale for by how high the fucking grass is. [Laughs.] Nah, it's up to the fender!

If you go on the Western train line that passes near here, you can go from the affluence of North Sydney, former Liberal Premier Barry O'Farrell's seat of Wahroonga, where they show off their wealth through their houses and they have people who actually wash their houses for them, and you can get it all the way out to Mount Druitt - and in Mount Druitt everyone's showing off their cars.

Showing off their rims!

If you can't afford the house to show off, it's the car you've got to show off.

That's a rich man's dream, showing off your car - more like showing off your Jordans [trainers]. You know what I mean?

So, [your song] 'Late Night Calls' - did you want to chat about that quickly?

'Late Night Calls' was about a cousin who got killed in a fight, he got stabbed and, erm, I knew I was going to write about it, but I wasn't sure how I was going to deliver it. And then it was like it was meant to happen, because, like, I got sent the beat from James from Sietta and then I was at the corner store and I'd seen this picture on the front of the newspaper and I went, 'Fuck.' You know what I mean? That's when it all clicked. That's when I got that line, looking at that face staring back from an article. That's when it clicked. After that it all came together, you know what I mean? I was there for my egg and bacon roll and that's another part of the story, you know what I mean? Like another piece of the puzzle that is Sheplife. That's why when I say it is, like, you know, as honest as I could be, it's with everything, you know what I mean? Death. Life, when I talk on 'Bigger Picture' about my daughter. I talk about my people on 'My People' and on 'Bad Apples' I talk about the youth. You know what I mean? It's multi-layered. Every piece of that puzzle is part of me. Every track is definitely a story. There's very little rapping for sport on there, you know what I mean?

On 'The Hunt' you say, 'The system ain't broken, it's the way that it works.' Tell us about that.

Well, it's what I've always said: The school system doesn't work for us, the jobs system doesn't work for us, the music system doesn't work for us, no system works for us - because that's the way that it works. It doesn't work FOR US, it's not broken. People say the system's broken - nah, that's how it WORKS. It's not broken - it's fucking working perfectly, because we're getting fucked! [Laughs.]

That's not the interpretation that's on [rap lyrics-analysing website] Rap Genius! [Laughs.] Did you see it?

Nah.

You want to go on there and correct it!

Why? What do they say?

Ah, they say, 'Briggs is saying the system may be broken, but the system is actually OK! It's not broken, he's saying it's a beautiful system.' [In fact what 'they' - user JustinYou - says is, 'Briggs suggests that this socio-political system isn’t so bad as to be labelled as broken. He believes the system works and success is better achieved by accepting that system rather than railing against it. The current Australian socio-political system is viewed by Briggs in a positive light overall, but he still acknowledges that alongside the benefits offered by that society there are some bad or challenging elements that ‘curse’ members of the indigenous population.'

http://rap.genius.com/4142992/Briggs-the-hunt-feat-gurrumul/Its-a-beautiful-thing-a-gift-and-a-curse-it-is-what-it-is-son-it-is-what-it-is]

Fuck... Yeah, that needs to be adjusted. [Laughs.]

So here's a copy of the paper that the interview will go in - it's a non-corporate paper and we cover a lot of political music, so that's why we started interviewing a lot of Indigenous hip-hop artists, because they had so much to say politically and they weren't getting much coverage. Then we had so many that I stuck them in the free book ['Real Talk: Aboriginal Rappers Talk About Their Music And Country' www.realtalkthebook.com], that you know about. I wanted to hear your criticisms of it, because obviously it's problematic when you do something like that, you can be seen as sticking people in a box and so on. I think Djarmbi said you were pissed off because you'd put all this work in and you weren't in it - and all these people who had put less work in were in it.

Yeah, well, it's like, I consider myself 'The Man', you know what I mean?

Sure.

And I wasn't in it and I was like, 'I'm the one making all the noise. Why the fuck am I not in it?' [Laughs.]

I was waiting for your next album release, because that's the only time artists will talk to you, when they have something to promote.

I talk all the time, flat out. But like, I've grown up, a lot. That stuff doesn't bother me any more, you know what I mean? I think that's from having my daughter as well, that just brought a whole different perspective. I've grown up a whole bunch since then, because like, your outlook changes and now it's like I couldn't give a damn about a book.

The whole thing was inappropriate really! I kind of got over-enthusiastic, including doing the Facebook page [www.facebook.com/AboriginalRap]. That's why it's so great that Frank and Renee have taken over the Indij Hip-Hop Show and have the time to do the social media side of it - especially people with such a radical perspective.

They're the best. They're the best. Your perspectives adjust, you know what I mean?

Having a kid certainly does that.

Yeah.

One of your lyrics is, 'I'm gettin paid for shows and that payment shows in this chain around my neck.' Another is: 'But I’m independent like the pendant on my necklace.' Tell us about that 'Negus chain' [a piss-take of other rappers' 'Jesus chains', which features a pendant modelled on the head of broadcaster and journalist George Negus].

Ah, that's like a $300 personal joke or whatever, man. [Laughs.] It's just a Negus piece - it just started out as a joke and the homeboy from Broken Lock who does custom jewellery and stuff like that, hooked it up.

Why Negus?

Because it rhymed with Jesus.

[Laughs.] And that's it? Not because he's Jesus-like?

Nah. It just rhymed with Jesus.

[Laughs.] Fair enough.

Simple.

Does he know about it?

Erm, I did tell him about it when I saw him on the street. Yeah, I did tell him about it. I didn't have it at the time, it was still getting made. But, yeah I did tell him about it.

So you know him well?

Negus?

Yeah.

Nah, I'd only - I just ran into him on the street one time.

Where was that?

Just in Melbourne. I was walking back to my hotel one night and I ran into him and [TV presenter] Ray Martin by chance.

He must have known you, though?

I don't know. I don't think so. It was just a chance meeting.

We only touched briefly on Gurrumul. So you're fast friends with him, right? I see you're always tweeting back and forth with [Gurrumul's record company] Skinnyfish.

Yep.

That's Gurrumul speaking to you, right?

No that's erm...

Through Mike Hohnen, or Mark...

That's [Skinnyfish founder] Mark Grose. I don't think Michael Hohnen does much tweeting. But yeah, I tweet Mark Grose.

OK. But tell us what you've learnt from Gurrumul, from hanging with him.

Erm, he's just - it's a whole other level of musicianship and work ethic. You know what I mean? It's a whole other ball park. So it makes you want to work harder. For real, that's what I took away from that mostly.

To work harder to attain a higher level in your music, or just to work harder?

Just a harder work ethic in general.

I tell you what, that was the song that really hit live at your Sydney show, for me anyway. You know when you get - it's really rare for me to get goosebumps up my back from music...

Hmmm.

I don't know how rare it is for you, but it's really rare for me. And when that came in, I just lost it.

[Briggs laughs.]

It was the Gurrumul song towards the end ['The Hunt'].

Yeah. It was a good show that one.

Yeah, you blew the roof off that place.

It was good fun.

Yeah. And speaking to people afterwards, they were all blown away by it.

That's cool. That's always nice to hear.

So Gurrumul bridges the gap [between black and white], like you, I think, in that you don't see colour, really, in my opinion. In that you work with [your record label] Golden Era.

Yep.

You make a point about you all being a big family, and Gurrumul's all about bridging the gap, from what I've read. Do you see that similarity between the two of you?

Erm, we also bridge the gap between the north and south [of Australia], ourselves, you know what I mean?

Yeah, right.

You know in the perspectives people hold of what's real, you know - what a 'real Aboriginal' is, you know what I mean?

Yeah, I think I know what you mean - you often get white activists going to the top of Australia to work with the 'real Aborigines'.

Yeah, to get the 'real Aboriginal experience', you know what I mean? So yeah. You know, I work with just whoever I've got a relationship with, you know what I mean? Who I work with is based upon who I connect with on a personal level, 90% of the time, and just the talent of somebody can also win me over. But I don't really go out and fish for a lot of collaborations, you know what I mean? Because if it doesn't feel natural, it doesn't feel right.

Yep. So one thing that I liked in the first part of your interview with Renee and Frank [on the Indij Hip-Hop Radio Show] the other week was when you were talking about being dismissed as an 'angry Aboriginal'.

Yeah.

Do you think that happens a lot with Indigenous hip-hop?

Erm, I don't know. Because, to be honest, I don't really read a lot of other people's reviews, you know what I mean? Like, I barely read my own. That's not to say I'm not interested, it's just that I work tirelessly on my own stuff, you know what I mean? So for me to stop - unless it really comes across my desk or whatever, I'm really not seeing it. So all I can speak from is just my experience with reviews - and a lot of people, you know, get stuck on my approach, you know what I mean? It's very blunt, it's very brazen, you know what I mean?

Yeah.

And a lot of the time they're taken aback. There's a few barriers you've got to get through before you can reach where my music comes from - and some people will never be there, you know what I mean? So that's just the reality of the industry, really. You know, not everyone's going to understand your message. Not everyone's going to understand your delivery - and that's just the way that it is. So a lot of people are going to have this kind of idea of this angry Aboriginal rap, but they don't really see the dynamics that I touch on, you know, with this record. And the fact is a lot of these people will never be able to because they've never experienced this kind of life and they, you know, and they won't know what it's like, you know what I mean? They're used to the one style of rap coming out of this country and they're used to, you know, what they know. So when someone who's loud and can be as aggressive as myself comes along, you know, it can be daunting for them to listen to.

You also said in that interview that you have to work 10 times harder to make it as an Aboriginal artist. But I'd have thought you have to work 10 times harder not only to get there, but also just being there, because it's far harder for Aboriginal people who are in the public eye, than it is for non-Aboriginal people, it seems to me.

When you're successful as an Aboriginal person, you're automatically expected to adhere to a certain standard of role model, of leadership - be it if you're a sports star, a musician, an artist or whatever, you know what I mean? There's a whole other level of responsibility that can be thrown upon you. And that's just another facet of being an Indigenous person of notoriety, whether you're in the bureaucracy, whether you're in the arts or whether you're in the sports or... As soon as you're in the spotlight, you know, you're going to have a magnifying glass on you to deliver a certain level of leadership, you know what I mean? So there's that to uphold. There's also the ideas that you have to be able to juggle, you know what I mean? Being an artist and being an Indigenous artist, you know what I mean? When I set out, I didn't want to be the best Aboriginal rapper. Nah, I wanted to be the best rapper, full stop, you know what I mean? I don't wanna disrespect rap, I don't wanna disrespect my culture, you know what I mean? I represent both in everything I do - hip-hop and my heritage and my family, you know what I mean? So, like, you don't go to the doctor because he's a black doctor, you don't go to the accountant because he's the black accountant. You go to the best accountant, you go to the best doctor. And that's what I had always set out to do, is be the best in my field. Then, on top of that, people don't understand that for anything, being black, you have to overcome a struggle every day. In the sense of the everyday stuff of your health, of your mental health and all of the above that is disregarded. So there's a plethora of just regular life shit that we have to overcome before we even are considering - that is sub-par to - this whole career business, it's just the life stuff, you know what I mean? And then there's the other stuff as well. It's just as an Indigenous person in this country you have to overcome, full stop. And the, you know, there'll be people that are hearing this interview or reading this interview and saying, 'But Aboriginal people get this and that.' And there's my case in point. That's the mindset, you know what I mean? That other mindset that we have to defeat every day. Ain't no-one paying my rent, man! You can ask Djarmbi!

You have to share a house with Djarmbi, is that right? [Laughs.]

Yeah.

You have to pay him rent?

Yeah, sometimes.

Or just deejay slots?

Yeah, I just give him a shout-out on Twitter.

[Laughs.] On 'Bad Move', you rap: 'Another bad move sonny, sayin' shit I know I'll get in trouble for, fuck Rolf Harris and his dumb cunt wobble board!' Of course, Aboriginal people have known for years that he was racist.

Yep.

That 'Bad Move' track came out maybe around the same time that Jaytee sampled him for the Last Kinection, right? [On 'I Still Call Australia Home'.]

I think they did that after I did 'Bad Move', yeah. I've always hated him.

I'm sure a lot of Aboriginal people have always hated him.

And then it just goes to show, for good reason, you know what I mean? I hope he rots. [Laughs.]

I did see that you put on social media, 'See I told you!'

[Laughs.] Yeah. I tried to warn everyone.

Yeah, 'Don't say I didn't warn ya!' That was it. So a lot of people must have felt vindicated when he was revealed as a nasty piece of work.

Yeah, but it's not even a sweet victory, you know what I mean? Because he's done some terrible things to some innocent people, disregarding his jokey, racist song. He's done some pretty serious things to some innocent kids - and for that I hope he dies a thousand deaths.

Yeah. I just wanted to touch on him because a lot of international readers will know him as a prominent Australian.

That's the thing, he's not even, man. He hasn't been here or living here for years.

He's not famous in Australia, really. But he's very well known in Britain, of course.

Yeah. He went to Britain and played that card, you know what I mean? And it just turns out he's just a filthy cocksucker, man. He can get whatever he gets, you know what I mean? He brings up a real bad taste in my - urgghhh - you know what I mean, he's just a wretched human. I just hate that snide and holier than thou approach that these people of his class and his calibre hold upon themselves and place upon themselves as the untouchables, you know what I mean? And then they try to play the old man card, who's sick, you know what I mean? Let him die in there, he can die in jail.

I'd imagine that being a successful artist and being where you come from, you must see the other end of the whole class spectrum as well.

Yeah.

As soon as you're a successful artist, you start getting people sucking up to you from all classes.

Hmmm. It's true.

Yeah. [Laughs.] Is it weird?

Yeah, it is weird. It is weird, because, like, I'm still very grounded, you know what I mean? I don't like going places that I can't take my cousins, you know what I mean? Everywhere I go I try to take someone with me who's my family, otherwise I get bored! I'm really not into that whole...

Shmoozing thing?

Nah. Nah. And cos I don't drink and I don't do drugs or nothing like that, partying and stuff doesn't really appeal to me, you know what I mean? I do the show and I meet some fans and whatever as much as I can and I leave and I go to the hotel and I go to bed.

Yeah. [Laughs.] Rock 'n' roll!

Yeah, man! [Laughs.] You know in comparison to what goes on, I'm pretty boring, you know what I mean - to what people would probably think goes on. And then, like, you've got other people who are, you know, stars and this and that and I'm just not interested, man. I just don't care about all that stuff, to be honest. You know, like, it's just not interesting to me, like, I'd much rather be having a laugh with my cousin.

So you were saying you've turned down some offers. What would they be? From people to play on their cruise ships?

Oh, just shows that I don't necessarily agree with or want to do. I can't really pinpoint any off the top of my head.

It's probably best not to anyway.

Yeah, well, I don't have a problem with it. If I turned it down, I turned it down for a reason.

No, I was thinking more like billionaires who wanted you to perform at their birthday party or something like this.

No, I don't do private shows, man. I'm not a stripper.

[Laughs.] So on 'Rather Be Dead', a lyric that I thought was really interesting was, 'I’m black and that feels, according to that, every recording I'm ordered to get to bridging the gap.'

Yeah, well that was just, again, talking about being an Indigenous artist, you know what I mean? It's like you're expected to talk about issues and this and that. And that's what I mean, 'I'm black and according to that, I'm ordered to get to bridging the gap', you know what I mean? And what I'm saying there is, just because I'm an Indigenous artist doesn't mean every track of mine... Cos when I wake up I'm a rapper as well, you know what I mean? I like rapping for sport. It's good fun. I like rapping because that's what I got into it for. You know what I mean? If you listen to a Ghost Face record, he doesn't talk about black nationalism all the time, you know what I mean? He doesn't have to. Because he is Ghost Face in everything that he does and you know what Ghost Face stands for - and that's what I'm about. I don't have to talk about that on every track because you know what I'm about, you know what I mean? It's like my presence on the radio is more than enough than my presence on social media, you know what I mean? It's like my whole being and my whole existence is based around my life and the truth and the honesty around that, you know what I mean? So in everything I do I represent my people and know that. You know what I mean? I'm just talking about, I don't have to walk out on stage flying the flag and doing the whole cliched routine about this and that and whatever, whatever. It's like, nah, I'm gonna rip the show better than anyone, you know what I mean? And at the end of the day, everyone's gonna know who I am and what I represent and what I do, you know what I mean?

Yeah, yeah. Do you feel like it's a competition of who can be the blackest, sometimes?

Nah, there is no competition. [Laughs.]

[Laughs.] So [on] 'Homemade Bombs' [you rap]: 'So I hit these streets with these homemade bombs / Take them to the place where my homeland was / Set it off, I'm a tear it down / You've gotta feel it now, you're gonna feel it now.'

Yeah, well that was like - jeez - I must have been barely - I was in my early 20s when I did that, you know what I mean?

And how old are you now?

I'm 28.

So that's like 2008, I think I wrote that. Jeez, it's a while ago now, but I guess 'Homemade Bombs' was just an analogy for the tracks, you know what I mean? And that's what I felt like I had, it's like, cos I'd made it all at home, in my bedroom, and in the basement, you know what I mean? I'm trying to think. It was a while ago now, man. Jeez. So what I'm saying is like, it's militant, right? It's a militant kind of track. And that was one of the first tracks I really stepped out with. And what I'm saying there is like, I built these bombs, these tracks, and I took them around the country and I brought them to the table, you know what I mean? And I'm going to set them off, you know what I mean? Like, 'You're going to listen to them, they're ill tracks.'

And when you say, 'Take them to the place where my homeland was'?

That's just Australia, isn't it. It's like, they took it. They didn't exactly, you know, do it nice. In a nice way! [Laughs.] So that's what I'm saying, it's like, you know, it's just a very militant kind of track. It's very. I was very young too, so it's very angry, you know what I mean? I can't even remember the lyrics to that one, it's been so long that I've ever done that. But yeah, what I'm saying is I'm just taking these songs and reminding people, you know what I mean? Like, this was like my terrorism. This was me being guerrilla about my approach, because it was all DIY, you know what I mean? So I felt like the Unabomber, man, just building these tracks in Shepparton, you know what I mean? Like, in the sticks with very little technology, you know what I mean? And I was going to take them around the country and I was going to take them to the capital cities and I was going to take them and these shows. That was what it was all about, you know what I mean?

Yeah. That's great. So on 'Greetings' you rap: 'What were they thinking sticking Briggs with these featherweights? My name resonates with the sorts of people Australian hip-hop celebrates. Bringing it to you in a better way.'

Yeah, that just means I'm better than everyone. [Laughs.]

OK! [Laughs.] Simple as that? But you do resonate with an Aussie Hip-Hop crowd, you really break into the mainstream.

Yeah, well, I resonated with the Hilltop Hoods. My name was in the traps with Reason and The Funkoars and the Hired Goons and the 750 Rebels and SBX, you know what I mean? My name was hanging around with all these different crews. Australian Hip-Hop celebrated Drapht, they celebrated Hilltop Hoods, they celebrated Obese Records, they celebrated, you know, Def Wish [Def Wish Cast] and all these different artists - and I'm saying that, you know, I'm reminding people that my name, you know, that my name is next to their name, you know, it resonates, people talk about me.

What's your secret, apart from quality?

My secret?

What do you reckon your secret is?

It's not really a secret.

No, it's not a secret, but what do you reckon your factor is?

Brand management. [Stifles a laugh.] Recognising myself as a brand.

Really?

Yeah, man. That's what it is. You've got to be a brand manager. You've got to be a multi-faceted conglomerate. [Lets out a snort.]

Nah, but it's probably catchiness and just quality that breaks down the doors, isn't it?

Yeah...

Humour, I think, plays a big part in it.

Yeah, well, I like to have a laugh, man - that's part of my being, you know what I mean? Like, having a laugh is part of my family. It's what we do the best. It's my favourite thing in the world, just having a laugh with my friends. That's my favourite thing in the world, man, next to hanging out with my daughter, is having a laugh with my friends. And then I get to do that ten-fold when I'm having a laugh on stage, you know what I mean?

Yeah. It's like two shows in one. It's like a stand-up comedy routine and a banging hip-hop show.

[Laughs.] I just like to talk, you know what I mean? I especially like shows where we play. I really like the intimacy, you know what I mean - that I can trap with the crowd and I can break it down and be like, you know, 'What's happenin'?' You know what I mean? Talk to them and see what's going on. I think my fans dig that, too and I want to be able to do that just in case things do get crazy and out of hand and bigger, you know what I mean? Like I want to be able to connect with these people and connect with my fans, who are my real fans. You know what I mean? The core 100 to 200 who come out to every show on this tour. Just in case things do blow up I want to know who my fans are, because I see people down the front row who know songs word-for-word and that's crazy to me. I want to remember these people, you know what I mean? Because they were there and that's why I like to talk to them, you know what I mean - and I like to give them - and that's why I like doing shows and that's why - you know, if anyone wants to know what I'm about, they've got to come to a show. They're not going to get the full idea just from listening to my records. Because I think if they come to my show they see the full spectrum of what makes up my character that is Briggs, you know what I mean? Cos Briggs is really Adam, like, amplified to 1000, you know what I mean?

Hmmm, yeah, yeah, yeah.

That's who Briggs is.

I was thinking when I was watching your Sydney gig, because you focus so much on your home of Shepparton on the album, I was thinking your real home is up there on stage, really.

Yeah, well, my whole thing with this 'Sheplife' show, was, like, this little spot first, a headlining tour, by myself. That's why I was genuinely really appreciative for everyone who came out.

You can see that on your social media and the fact that you meet fans and it's very easy for fans to just say, 'Can I come meet you at the gig and bring my daughter?' or whatever and you're just, like, 'Sure.'

Yeah!

And that's what's so appealing is, it's actually harder to interview you, than it is to meet you as a fan.

[Briggs laughs.]

It's a lot harder to go through your management, but that's great. That's a great thing.

Yeah well, I'm very open...

Because the fans should, you know, the fans should come first.

Yeah, well, I like to keep, like, an even playing field, you know what I mean? Like, I feel, like, for every person I do that for, you know what I mean, like, that means a whole lot more to them than them buying a CD, you know what I mean? I forget, you know, the kind of impact that I can have on people. To still be - you know, I'm not trying to take the piss or nothing - but I do forget that people do see me in a different light than what I see myself.

Sure.

And, you know, the Hilltop Hoods taught me a lot about that. About being nice, you know what I mean? Because I'm from a country town where if someone's yelling out your name, half the time they're trying to offer you out! [Laughs.] So it took me a while to get to know that, you know what I mean? People coming up and saying, 'Briggs!' and I'm saying, 'This cunt wants to have a fucking crack!' You know what I mean? Then they're like, 'Can we get a photo?' And you're like, 'Oh, cool, cool, cool.' [Laughs.] Because normally if I was walking down the street when I was growing up, it'd be, 'BRIGGSY!' 'This cunt!' You know what I mean? Like, 'Not again!' [Laughs.] And that's the reality. I'm still adjusting to that kind of stuff as well and, like, I wouldn't say I'm, like, a super-shy person, you know what I mean? But I think I'm definitely a little bit different from what people would expect.

Offstage?

Yeah, I'm like, I'm not... If I don't know you or don't know who you are or whatever I'm definitely way more reserved than I am with my family, who I'm comfortable with, you know what I mean? And that's why I say, 'If you want to meet me, that's cool, but it's probably going to be a disappointing experience.' [Laughs.] I'm just like, 'Whatever, that's cool, whatever.' That said, as I've always said - and I say it at the end of every show - I'm so very appreciative of everyone who does come out and support - because that's when it makes sense. Charts and whatever I couldn't give a fuck about, you know what I mean? That lasts for a little bit, but when you do the live show, that's what you remember, you know what I mean?

Yeah, for sure. So on Victory you rap: 'My people proud, my friends around, but I'm sick of burying my cousins / I'm real sick of losin my brothers, who couldn't make it outta that gutter / A win for me, is a win for them, I got more to lose than these others.' We talked about that regarding 'Late Night Calls', but did you want to add anything?