Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention

Manning Marable

Penguin, 2011

596 pp. (hb), $49.95

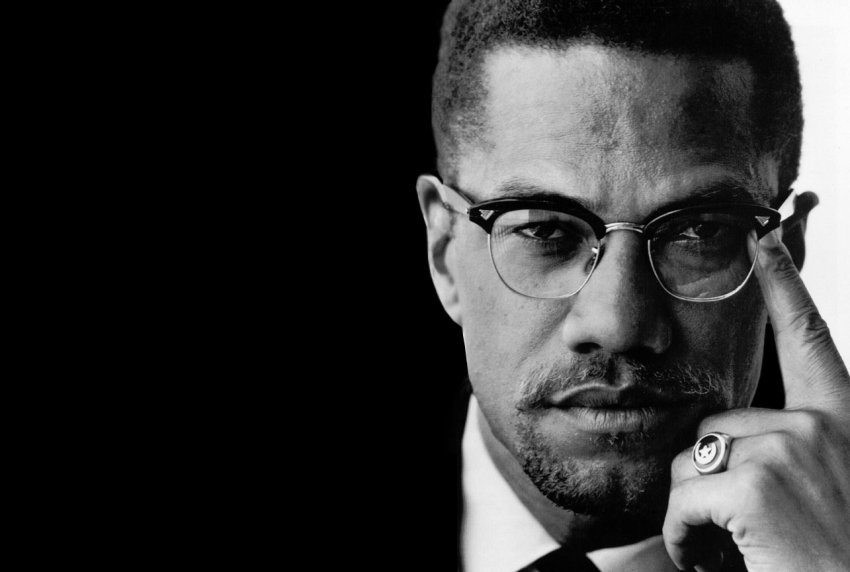

“If you’re not careful, the newspapers will have you hating the oppressed and loving the people doing the oppressing,” African American revolutionary Malcolm X, assassinated in 1965 at the age of 39, once said in a comment on the capitalist media that applies to contemporary reporting on English riots or refugees.

Malcolm, who increasingly saw the link between capitalism and racial oppression in the last years of his life, said: “You can't have capitalism without racism.”

“You show me a capitalist, and I'll show you a bloodsucker,” said the man once described as the only Black man who “could stop a race riot … or start one”.

Malcolm X strode through the US political landscape of the late 1950s and early '60s, towering over his times with his burning righteousness and intelligence.

Malcolm was a hugely influential figure and inspiration for the radical movement for Black liberation that grew in the late 60s.

“His aura was too bright,” Manning Marable, author of this important new biography of the African American revolutionary, quotes the poet Maya Angelou on her meeting with Malcolm.

“A hot desert storm eddied around him and rushed to me, making my skin contract, and my pores slam shut.”

Malcolm had that effect on people; in the case of white America it generated violent hatred and official conspiracies that played a part in his assassination.

In the Black community, his withering polemics against racism converted masses to the Nation of Islam (NOI) religious sect — and later attracted a new generation of activists who wanted to follow him towards a radical vision for a United States' revolution.

The NOI preached Black pride, but combined it with an appeal to separation from white America. This meant its fierce defence of NOI members (not the entire Black community) was joined with a passive political approach that offered no way forward.

Mixed with a violently toxic internal discipline, the NOI was an arena in which someone of Malcolm’s acumen could only grow for a while.

But it inevitably proved constricting as the civil rights movement surged forward in the early '60s.

The power of Malcolm's developing militant thinking was such that a New York Police Department (NYPD) officer assigned to listen to the countless microphones that bugged every aspect of Malcolm’s life found himself, against his will, convinced that Malcolm was talking the truth about the US and offered a way forward.

That story and more tumble out of this meticulous examination of Malcolm’s life from his impoverished childhood, through his hustling years of petty crime, conversion to the NOI during his 1946-'52 stint in prison, his rise as a radical preacher in Harlem and his final frantic period of trying to map out an alternative path for Afro-American liberation allied to the rising African revolutionary wave.

This, for Marable, was Malcolm’s “life of reinvention”.

The story has been told before in Alex Haley’s The Autobiography of Malcolm X. But Marable has harnessed the resources of Columbia University’s Malcolm X Project to dig into nearly every moment of Malcolm’s life to produce what will become the standard reference.

Nearly all paragraphs are buttressed with an entire matrix of sources to verify Marable’s claims, and some remarkable assertions are made.

Important details differ from Haley’s narrative — which was based on conversations with Malcolm and published after Malcolm's assassination in 1965.

Haley explains Malcolm’s rupture with the NOI in '63-64 as caused by the hypocritical womanising of Elijah Muhammad, which certainly did play a role.

But Marable raises Malcolm's growing discussions with, and attempts to find a way to relate to, the growing civil rights movement.

Malcolm was concerned with ways to fight racism, not simply denounce it.

One example Marable gives relates to the 1962 attack by Los Angeles police on an NOI mosque, murdering one man and paralysing another.

In all, seven Black Muslims were shot.

The survivors were framed up on serious charges.

Malcolm seriously attempted to organise a squad that would assassinate members of the Los Angeles Police Department in retaliation.

Elijah Muhammad vetoed this operation.

Malcolm saw the limitations of the NOI framework, leading to the conflict that drove him out of the NOI.

After officially leaving the NOI in March 1964, Malcolm began the two great travels that changed the nature of his religious and political thinking.

He travelled twice to Africa and the Middle East, including a Hajj to Mecca, converting to orthodox Sunni Islam in the process.

He also travelled downtown in New York City and met with the Trotskyists of the Socialist Workers Party.

In Africa, Malcolm saw the growth of pan-African, anti-colonial radicalism and he conceived a plan to generate an equivalent in the US.

With the Trotskyists, he discussed the possibilities of revolutionary action in the US, welcomed their paper sellers at his meetings and addressed their public forums.

He also reached out to other radicals in the States.

All the while, he had to live on the run.

The NOI wanted him dead because his example threatened to overshadow that of Elijah Muhammad.

Marable’s narrative becomes a little scattered at this point because Malcolm was sleeping in different places and keeping low.

However, fascinating snippets emerge.

Shortly before his death, Malcolm had a private meeting with legendary Argentinean-born revolutionary Che Guevara, a central leader of the Cuban Revolution.

If we are lucky, perhaps a record of the meeting is kept on file in Havana.

Another detail is one of Malcolm’s body guards recalling that towards the end, he was hungrily devouring German philosopher Hegel’s account of the master and the slave in Phenomenology of Spirit.

It is a philosophical explanation of the creation of the slave mentality, something that had always formed a centrepiece of Malcolm’s rhetoric.

But Malcolm was fated to not bring that broader philosophical tradition to his audience (as Afro-Caribbean revolutionary Frantz Fannon did with Black Skin, White Masks).

Some of the new details revealed by Marable are of a personal nature.

Marable reveals that Malcolm included some homosexual hustling in his petty crime days — something that never appeared in Haley’s book.

The Malcolm that emerges in Marable’s account is more human and stark than the saint of the Autobiography. Yet he is all the more inspiring for it.

Ordinary humans, with all their failings and faults, can walk in the footsteps of this Malcolm.

Marable reveals Malcolm’s misogyny, for example.

Malcolm had a disrupted relationship with his parents.

His father was murdered by racists and his mother driven insane by the pressures of raising a raft of children single-handed while constantly harassed by racist officials.

Malcolm was left with a sense of abandonment and an inability to trust women, which resulted in his tendency to disregard them.

Among the behaviours this produced in the adult Malcolm was his habit of leaving home for extended political journeys immediately after his wife, Betty Shabazz, gave birth to each of their children.

In the final year of his life Malcolm started to develop his thinking. After his visit to Africa and the Middle East in 1964, Malcolm said: “In every country you go to, usually the degree of progress can never be separated from the [position of the] woman...

“I am frankly proud of the contributions that our women have made in the struggle for freedom and I’m one person who’s for giving them all the leeway possible because they’ve made a greater contribution than many of us men.”

Malcolm's developing views led him to appoint a woman to head the Organization of Afro-American Unity, the secular political movement he set his hopes on.

At the time of his assassination, Malcolm was having an affair with an 18-year-old woman, and there is a strong inference that she was complicit in the murder.

Marable details the entire NOI conspiracy to kill Malcolm in February 1965. But he also exposes, in detail, the evidence that points to the NYPD and FBI as being equally responsible.

The brutality of the murder, recounted with forensic precision, is sickening.

Equally repulsive is the brazenness of the NYPD refusal to properly investigate it.

In fact, one of the hit men who pumped bullets into Malcolm could very easily have been a cop.

The NYPD and the FBI refused Marable access to their files.

Malcolm X’s monument is the revolutionary struggle of the Black masses, in the US and Africa.

In the US, I once heard a chant at a demonstration that is amplified through this book: “Malcolm X, live like him! Dare to struggle, dare to win!”

Video: Malcolm X. Oxford Union Debate, Dec. 3 1964 - avereos. Malcolm X gives a speech at Oxford University in 1964: 'We are living in a time of revolution, a time when there has got to be a change. The people in power have misused it, and now a better world must be built ... And I, for one, will join in with anyone, I don't care what colour you are, as long as you want a change to the miserable conditions that exist on this Earth.'