Starting at Zero: His own story

By Jimi Hendrix (edited by Peter Neal)

Bloomsbury, 2014

203 pp., $19.99

Jimi Hendrix Soundscapes

By Marie-Paule MacDonald

Reaktion, 2016

300 pp., $37.99

In 1967, Jimi Hendrix’s management decided to introduce him to American audiences through working as an opening act for the Monkees.

The Monkees were a contrived, plastic-Beatles imitation band put together by jaded entrepreneurs. An 11-year-old kid was taken to his first concert at one of those dates. Marie-Paule MacDonald quotes him saying: “I had no idea who Jimi Hendrix was, but it was incredible.”

He can’t even remember the Monkees that night. “All I can remember is everyone screaming, standing on chairs, jumping up and down, waving their arms in the air and being entranced by Jimi Hendrix on that stage.

“The music was like nothing I had ever heard and the crowd was in a fever when he was on stage. The last thing I remember of the evening was him setting his guitar on fire.”

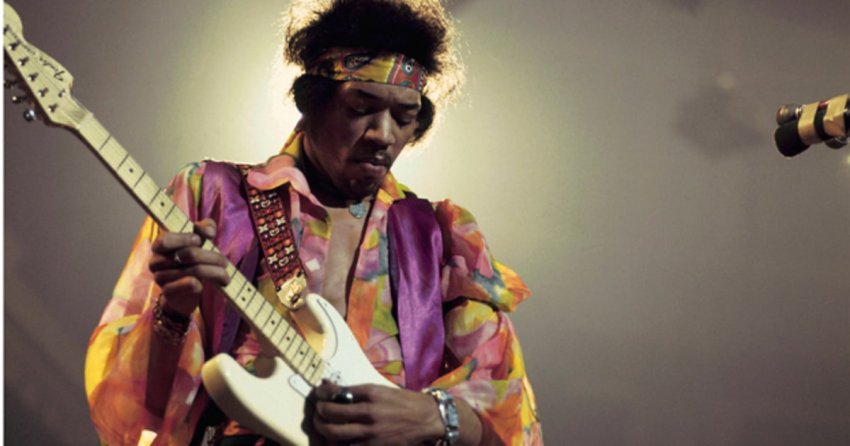

Hendrix, possibly the greatest-ever rock guitarist, arrived in public consciousness at exactly the right moment. His music summarised the desire of millions of youth to break through to a new society.

He also embodied the sexual revolution. Germaine Greer was just one who said she felt that a doorway to a newer, freer sexuality opened up for her when she met Hendrix.

Having learned his craft playing in Black bands endlessly touring the southern US, he hit London in September, 1966. He immediately became one of the era’s most glamourous stars and never stopped his artistic evolution until his tragic death in 1970.

The sonic overload that he manipulated to harmonic effect aligned with the rebellious anti-war demonstrators and Black revolutionaries in the streets. Starting at Zero, which is entirely cobbled together from recordings of Hendrix — with short supplementary memoirs of close associates — shows that Hendrix identified with that revolution.

“There’s this song that I’m writing now that’s dedicated to the Black Panthers,” he told a reporter in 1969 about the militant Black revolutionary group. That song was the astonishing “Voodoo Chile (Slight Return)”, which he played from one side of the United States to the other.

Hendrix agreed to do fundraising concerts for the Panthers, but that arrangement fell through.

On stage in 1970, straight after four anti-war protesters were shot dead by the National guard at Kent State University, Hendrix said: “This is dedicated to all the soldiers fightin’ in Kent State — all four of them!”

“What a DRAG that America’s guns have made the CRACK in the Liberty Bell their symbol,” he once said. Jimi Hendrix’s music opened a crack in reality through which a better world can be seen.