Women’s Liberation House in Alberta Street in Sydney’s CBD, set up in 1972, represented a consolidation of the second wave of modern, organised feminism, which grew during the 1960s-1970s in Britain, the United States, Europe and Australia. Frances Hamilton was active in the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM). Below, she recounts some experiences from that time at Green Left's inaugural Feminist Walking Tour in August.

• • •

The first wave of the women's liberation movement, which began in the late 19th century and continued into the beginning of the 20th, focussed on suffrage — to gain women the right to vote and stand for parliament.

The second wave sought social and political change for women including an end to sexual discrimination and for full legal, economic, vocational, education and social rights and opportunities.

Reproductive rights was a major focus for the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM). The contraceptive pill was available, but taxed as a luxury item at 27.5%. It could not be advertised and family planning services were forbidden.

Abortion was illegal, except for very narrow criteria, such as being mentally unsound. So, women had backyard abortions, which were extremely dangerous, which often lead to sterility and sometimes even death.

Doctors were seen as always knowing best and normal events, like pregnancy and childbirth, were treated as illnesses which only a doctor could comprehend.

There was complete silence about domestic violence, rape, incest and venereal disease. Homosexuality was another forbidden topic.

There were no women and children refuges, or sexual assault services.

Women received 75% of the male wage and were precluded from many jobs and industries.

Female public servants had to retire on marriage, as did many women in private industry.

I was retired from the federal public service at the age of 21 when I married, although I continued to work elsewhere until my retirement 45 years later. It was also commonplace among men (and many women) to see a woman’s place as being in the home, and education being wasted on girls.

Organising deepens

From the late 1960s, women in Sydney, Newcastle, Melbourne and Adelaide started to hold regular meetings.

In 1969, the WLM lodged a submission on equal pay to the Federal Arbitration Commission.

The first Women’s Liberation National Conference was held at Melbourne University in 1970. A week later, Sydney University hosted a public meeting organised by a coalition of groups aimed at changing abortion laws. Later, an abortion rights march was organised by Women’s Lib, Children by Choice and Abortion on Request.

By the end of 1971, about 16 Women’s Lib groups had been set up in Sydney. They needed a premises to cater for their expanding activities and Women’s Liberation House, known as “The House”, was rented in first in Glebe, and later in May 1972 it moved to Alberta Street.

It became the meeting place for many women’s groups, as well as the WLM. It was an important point of contact for women seeking information and to become involved in activism: meetings, discussions and working bees all took place there.

The Sydney Working Women’s Group, the Women’s Abortion Action Campaign (WWAC), Women in Education Group, Lesbian Space — which ran a phone counseling service from the house — Women’s Incest Survivor Network and Gay Liberation all organised under the umbrella of Women’s Lib.

Women from all sectors — academics, university and high school students, teachers, trade union members, housewives, public servants and workers from a variety of industries — started organising.

I remember meeting women from the ALP and the Communist Party of Australia, but never anyone from the Liberal or Country Parties: they may have been there, but they did not say. All ages, from the very young to older women with much life experience, organised together.

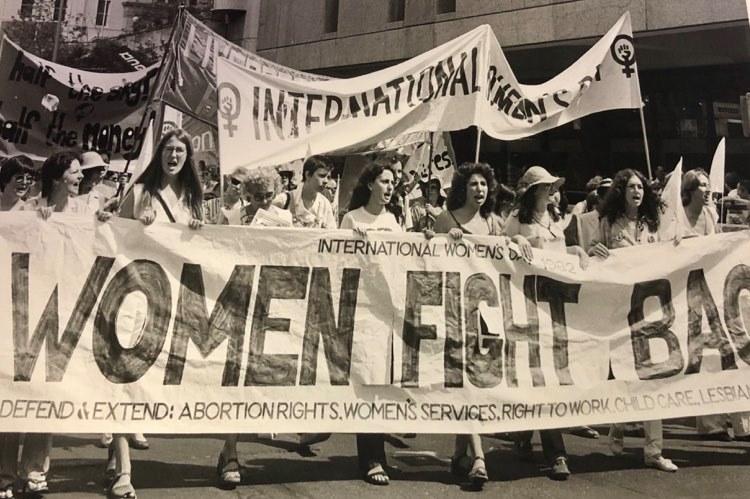

iwd_melbourne_1982_credit_green_left_archives.jpg

Feminist-run services

Over a few years, The Rape Crisis Centre’s first telephone counseling service, the Lesbian Line Counseling Service and the Birth Control and Abortion Referral Service were set up.

The MeJane, Scarlet Woman and Refractory Girl collectives also met there and printed material on the premises. MeJane was the WLM’s first newspaper.

From 1970 to 1999, the Sydney Women’s Liberation Newsletter was also printed there. A range of materials, debating and informing women about feminist ideas and analysing women’s position in society, were disseminated from the house.

This material was well written, knowledgeable and persuasive. For example, in 1971, 18,000 leaflets were distributed on how to protect against pregnancy and how to recognise venereal diseases.

The Women’s Electoral Lobby held its first meeting in the House. They surveyed every candidate for their views on vital issues ahead of the federal election and the survey and the Melbourne Age published a lift-out list of the results.

The Labor candidates had replied positively to many of the questions and the Labor leadership committed to honour many changes.

Subsequently the Gough Whitlam government in 1973 reconvened the Arbitration Commission to open the equal pay case and it adopted the principle of equal pay for equal work.

It removed the 27.5% luxury sales tax on the contraceptive pill and revoked the ban on advertising contraceptives in the ACT.

Abortion was a state issue, but the federal government did support family planning services in community health centres. It appointed a special advisor to the PM on women’s issues; passed the new Family Law Act, which introduced no-fault divorce and fairer distribution of assets; provided sole parents with a pension; provided a universal health cover (Medibank); and developed the concept of preventative medicine.

Funding for services

The WLM was buoyed by all this and got to work. It was an extremely exciting time.

In 1973, it set up an abortion referral service in WLH, run by women. Volunteers offered information about the available options, provided pregnancy testing, contraceptive advice and gave support.

In 1974, the Elsie Women’s Refuge for Women and Children was set up in Glebe (the first of its kind), the Leichhardt Women’s Community Health Centre was set up and the first Rape Crisis Centre was set up in Women’s House.

In 1975, the Liverpool Women’s Health Centre and the Newcastle Working Women’s Centre were set up with government funding.

The Abortion Referral Service, Elsie Women’s Refuge and the Rape Crisis Centre started to receive federal government funding. But, after the government was dismissed in 1975, the Coalition started to wind back services, although the Labor government in New South Wales continued many of them.

While women’s refuges still exist, most are no longer operated by feminists, with federal funding going to church groups: the Elsie Refuge has been run by the St Vincent de Paul Society since 2014.

Rape crisis centres, which had been set up nationwide, have also suffered under funding cuts. The last state to decriminalise abortion was NSW, last year.

The women’s liberation movement has much more to do to enforce equality in law and in practice.

[Another Feminist Walking Tour is planned for November 1. Get in touch if you would like to attend this COVID-19 safe event.]