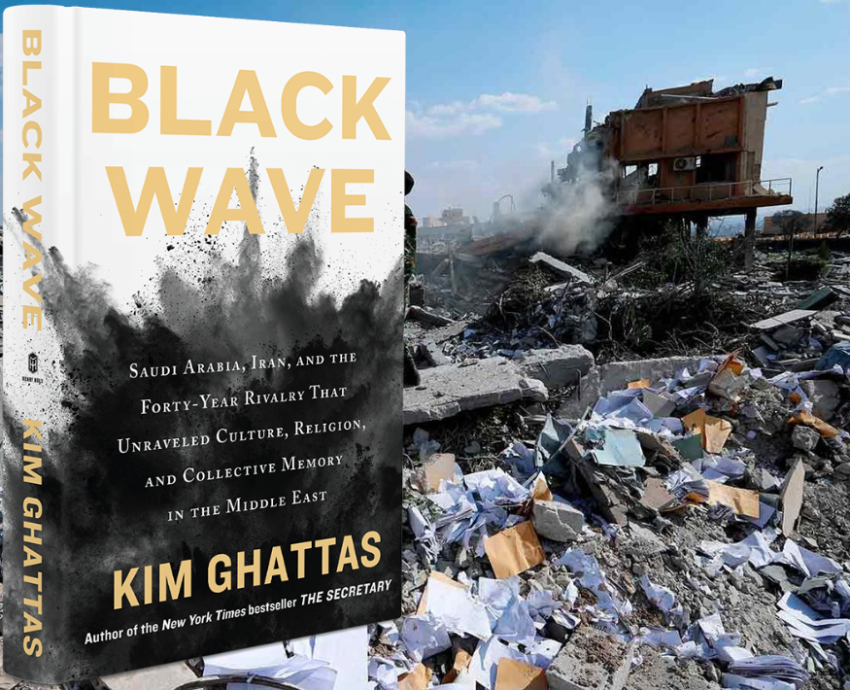

Black Wave: Saudi Arabia, Iran and the rivalry that unravelled the Middle EastBy Kim Ghattas.Wildfire, London, 2020

This book explores the rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and their struggle for influence in the Islamic world. Both countries have used oil revenue to promote their versions of Islam, and to fund armed groups in other countries. This rivalry has contributed to violent conflicts in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Egypt and elsewhere.

According to Ghattas, 1979 was a turning point. This was the year of the Iranian revolution. It was also the year when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. Another less well-known event was the seizure of the Holy Mosque in Mecca by a group of armed men claiming that the Saudi monarchy had betrayed Islam.

Iran

Before 1979, Iran was an absolute monarchy headed by the shah (king). In 1953 a United States-organised coup had brought down Mohammad Mossadegh, a popular nationalist prime minister who had asserted his independence from the shah and tried to nationalise the oil industry.

The shah's brutal regime was opposed by leftists, nationalists and a section of the Islamic clergy. But these groups had different visions of what should replace the monarchy.

The leading clerical opponent of the shah was Ayatollah Khomeini, who had been in exile since 1965, first in Iraq and then in France. According to Ghattas, he propagated dual messages. In interviews with the Western media, he appeared to be a supporter of democracy (Ghattas says that his translators often distorted what he said to give a more favourable impression). To his followers, he talked of an Islamic state, under the guardianship of an Islamic jurist (a system called wilayat al-faqih).

In January, 1979, following a wave of mass protests, the shah fled Iran, and in February, Khomeini returned. He quickly began to implement his ideas.

He established a provisional government composed of his supporters. He held a referendum to endorse the idea of an Islamic republic, without a clear definition of what this meant.

Leftists still had mass support, but they were attacked by pro-Khomeini thugs.

In November, 1979, pro-Khomeini students took over the US embassy and held the staff hostage. This enabled Khomeini to outbid the left in anti-imperialist rhetoric.

In December, a new constitution was put to a referendum. It made Shia Islam the state religion and included the concept of wilayat al-faqih, enabling Khomeini to become the supreme leader.

The religious police enforced compulsory head covering for women. The universities were shut down for three years beginning in 1980, and a purge of staff and students was carried out. Mass executions killed thousands of people.

In subsequent decades there have been waves of protest that have been violently repressed.

Saudi Arabia

The Saudi monarchy seized control of most of the Arabian peninsula in the 1920s with the ideological support of the Wahhabis, an extremely reactionary section of the Islamic clergy who followed the ideas of 18th-century preacher Muhammad ibn Abdelwahhab. The kingdom was allied with Britain, receiving subsidies and military assistance.

In 1945, the Saudi monarchy formed an alliance with the US, which offered protection in exchange for access to Saudi Arabia's oil.

In November, 1979, the Holy Mosque in Mecca was taken over by 300 armed men. Their leader Juhayman al-Otaibi was a product of Wahhabi education, but believed the monarchy had betrayed Islam. He wanted to overthrow the royal family and cut ties with the West. On December 4, the Saudi army stormed the mosque and crushed the revolt.

At around the same time there was a rebellion by Shia Muslims in Saudi Arabia's eastern province. However, there was no possibility of unity amongst the two groups of rebels, because Juhayman's followers shared the Wahhabi hostility to all other religious groups, including Shia Muslims.

Following the rebellion, the monarchy moved to strengthen its alliance with the Wahhabi clergy by intensifying its reactionary social policies. The religious police were given increased powers to terrorise people and enforce segregation of men and women in public. Women were banned from appearing on TV.

Saudi Arabia also stepped up its efforts to promote its version of Islam internationally. Since the 1960s, it had used oil money to promote Islam as a counter to communism and pan-Arab nationalism. This funding was boosted after 1979. Afghanistan was a major target.

Afghanistan

In April 1978, a leftist party seized power in Afghanistan. (Ghattas refers to it as the "Communist Party", though its official name was the Peoples Democratic Party of Afghanistan - PDPA). Islamist rebels waged war against the PDPA government, with the support of Pakistan, the US and Saudi Arabia. The Soviet Union, fearing a possible rebel victory, invaded Afghanistan in December 1979.

Ghattas does not discuss the nature of the PDPA government, which had progressive policies on issues such as women's rights and land reform, but was clumsy in implementing them, thereby alienating many people, and was also torn by bloody factionalism.

The Saudi leadership saw the war in Afghanistan as an opportunity to restore their reputations as champions of Islam, after the siege of the Holy Mosque. They could send religious zealots to Afghanistan to fight the Soviet Union, shifting their focus away from the sins of the royal family.

Saudi money funded thousands of fighters from across the Arab world who went to fight in Afghanistan. They were based in the city of Peshawar in Pakistan, with the support of the Pakistani military dictatorship and the US government. Osama bin Laden, son of a wealthy Saudi family, became their leader.

In February 1989 the last Soviet troops left Afghanistan. The PDPA government held on for a while, but was eventually overthrown. But then the different rebel groups fought each other. After several years of bloodshed, a newly formed group called the Taliban took control of much of the country.

Many Taliban fighters were graduates of Saudi-funded religious schools in Pakistan. The Taliban imposed a very intolerant version of Islam in the areas they controlled. The Taliban's religious police were trained by the Saudi religious police.

Osama bin Laden returned to Saudi Arabia, but became dissatisfied with the Saudi monarchy. He disagreed with the presence of US troops in the country. After a period in Sudan he returned to Afghanistan. Together with other veterans of the war against the Soviet Union, he built al-Qaeda, which carried out a series of attacks on US targets in the Middle East and Africa, culminating in the attacks on the US itself on September 11, 2011.

Pakistan

Military dictators in Pakistan had a history of using Islam as a rallying cry against India. Zia ul-Haq, who came to power in a military coup in 1977, carried this much further. In February 1979, he announced plans to introduce sharia law, with a new legal code providing that drinkers would be flogged, adulterers would be stoned to death, and thieves would have their hands chopped off.

In 1983, Zia introduced a law saying that a woman's testimony was worth only half a man's testimony in court. There were mass protests by women and their male supporters, which were violently repressed.

Zia received aid from the US and from the Gulf states. Saudi Arabia poured vast amounts of money into mosques and Islamic schools in Pakistan that propagated a reactionary version of Islam.

One result of this was a growth of religious sectarianism. Saudi-funded mosques portrayed Shia Muslims as kafir (infidels). The Saudis produced anti-Shia pamphlets that were distributed around the world, including in Pakistan. Sporadic Sunni-Shia violence began in 1986, and large-scale violence in 1987.

Zia died in a plane crash in 1988, but his legacy continues. According to Ghattas: "Everything had shifted to the right: the old extremes were the new centre — or so it felt".

Reactionary laws, sectarian violence, and repression of religious minorities continued.

Egypt

Anwar Sadat became president of Egypt after the death of Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1970. Sadat moved Egypt away from its alliance with the Soviet Union and towards an alliance with the US and Saudi Arabia.

He used religion as a tool to gain legitimacy. He amended the constitution to make Islam the principal source of legislation. He facilitated the growth of Islamic groups on campus to counter the left. Islamists gained control of most student unions. But when Sadat signed a peace treaty with Israel in 1979, many Islamists turned against him. Sadat was murdered by an Islamist group in 1981.

His successor Hosni Mubarak encouraged Islamists to join the Saudi-funded war in Afghanistan. Ayman al-Zawahiri, an Egyptian lslamist, later became Osama bin Laden's second in command.

Within Egypt, the combined effect of reactionary legislation and the violence of Islamist terrorist groups created a very repressive environment.

In January 2011, mass protests demanded the removal of Mubarak. Over 800 protestors were killed, but in February Mubarak resigned. A presidential election was held in 2012. It was won by Mohammad Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood.

The Saudi leadership was unhappy with Morsi's victory. According to Ghattas, this was because a victory for political Islam through the ballot box could feed calls for elections in Saudi Arabia. Also, Morsi wanted to establish friendly relations with Iran.

The revolutionaries who had led the overthrow of Mubarak opposed Morsi for different reasons. They protested against his plans for an Islamist constitution.

The army used these protests as a pretext for a coup against Morsi and a massacre of hundreds of his supporters. After the coup, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates showed their support by pledging US$8 billion of aid to the coup regime.

Lebanon

In 1982, Israel invaded southern Lebanon and Beirut. The invaders faced resistance from leftist and nationalist forces.

Iran sent a contingent of Revolutionary Guards to the town of Baalbek in eastern Lebanon. While this area was not under Israeli occupation, the Revolutionary Guards trained Lebanese Shia youth to fight the Israelis. These people became the nucleus of Hezbollah, whose existence was publicly announced in 1985.

The Iranians who, according to Ghattas, had "a lot of money", built a hospital and provided services. But they also imposed religious restrictions, banning music and alcohol.

Hezbollah, with Iranian aid, grew stronger and eventually forced Israel to withdraw from Lebanon in 2000. But they also imposed religious rules and repressed the left in the areas they controlled.

Iraq

Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein invaded Iran in September 1980, seemingly with the encouragement of Saudi Arabia (he had visited Saudi Arabia before launching the invasion, and later received financial support for the war effort).

The war ended in 1988, after causing terrible devastation and loss of life in both countries.

The alliance between Iraq and Saudi Arabia was broken when, in August 1990, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. He was driven out in early 1991 by an alliance including the US and Saudi Arabia.

In 2003, the US invaded Iraq, and seemed to have won an easy victory. The Iraqi army was disbanded. But former officers and soldiers began a guerrilla resistance.

Some of these soldiers had been influenced by the Saudi version of Islam. They linked up with Ansar al-Islam, a group set up by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who had been in Afghanistan with Osama bin Laden, to create a group known as al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI).

The US installed a predominantly Shia government in Iraq. AQI carried out terrorist attacks against Shias, while Shia militias responded with terrorist attacks on Sunnis. The result was sectarian war.

Syria

In 2011, there was an uprising against the dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad. But within a few years Syria "found itself caught between the spiritual heirs of Ibn Abdelwahhab and the upholders of Khomeini's legacy; between the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)".

Ghattas attributes this partly to "the inexorable radicalisation and militarisation of any revolution that drags on too long". But she also looks at the intervention of outside forces in the Syrian conflict.

The IRGC and Lebanese Hezbollah sent troops to support the Assad regime. Iran also recruited Shias from Afghanistan and Pakistan to fight. The Russian air force bombarded rebel-controlled towns.

Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states supported the rebels, though rivalries amongst the Gulf states prevented them from working together. Saudi Arabia supported a group called the Army of Islam, which established a brutal regime in the areas it controlled. For example, it abducted and presumably murdered four human rights activists in December 2013. Its leader Zahran Alloush called for Syria to be cleansed of Shias.

AQI sent representatives into Syria to link up with local Islamic extremists, and changed its name to the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

Ghattas does not mention Turkey's role in arming selected rebel groups, including ISIS. Turkey's main aim was to use such groups to attack the Rojava revolution, a democratic revolution that began in three predominantly Kurdish areas of northern Syria and began to spread to nearby areas inhabited by other ethnic groups. Turkey also sent its own troops to invade and occupy parts of northern Syria.

The Rojava revolution is not mentioned in the book, a serious omission.

ISIS

In 2014, ISIS took control of large parts of Iraq and Syria. It tried to invade Rojava, but was driven back by the revolutionary forces. This was a turning point. In subsequent years ISIS lost most of the territory it had captured in Syria and Iraq.

Ghattas says that ISIS is "Wahhabism untamed, in its purest form". ISIS declared war on the Saudi royal family for supposedly departing from Wahhabi principles. But according to Ghattas, "ISIS was Saudi progeny, the by-product of decades of Saudi-driven proselytising and funding of a specific school of thought that crushed all others, but it was also a rebel child, a reaction to Saudi Arabia's own hypocrisy, as it claimed to be the embodiment of an Islamic state while being an ally of the West".

Hope for the future

Despite the repression and sectarian violence, Ghattas is hopeful, because of the people who "continue their relentless, courageous fight for more freedoms, more tolerance, more light".

They include women in Saudi Arabia who campaigned for the right to drive. They eventually won this right, but eleven of the campaigners were arrested and kept in prison even after the law had changed.

They also include people in Iran campaigning for democracy, workers' rights and women's rights.

Ghattas also cites the "extraordinary protests against corruption and poverty, but also against sectarianism" in Iraq and Lebanon in October 2019.

I would add the Rojava revolution, made by the people of northern and eastern Syria who are trying to build an alternative to both the Assad dictatorship and the Turkish-backed sectarian groups.