Transnational companies are forging ahead with plans to exploit the seafloor for valuable minerals, despite widespread concerns about the potential ecological and climate impacts. Large-scale deep-sea mining involves the extraction of polymetallic nodules, which are small rocks formed over millions of years containing cobalt, nickel, copper and manganese.

Mining companies are seeking to exploit an area of seafloor in the Pacific Ocean about the size of Europe, known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ). Despite a lack of formal laws, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) — tasked with regulating deep-sea mining under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea — has already granted 31 “exploration” permits to 22 contractors.

The Metals Company — a Canadian deep-sea mining company — completed a so-called “trial” in the CCZ in November last year, which environmental campaigners described as mining disguised as research. During the project, the mining vehicle disturbed more than 80 kilometres of seafloor and collected 4500 tonnes of nodules.

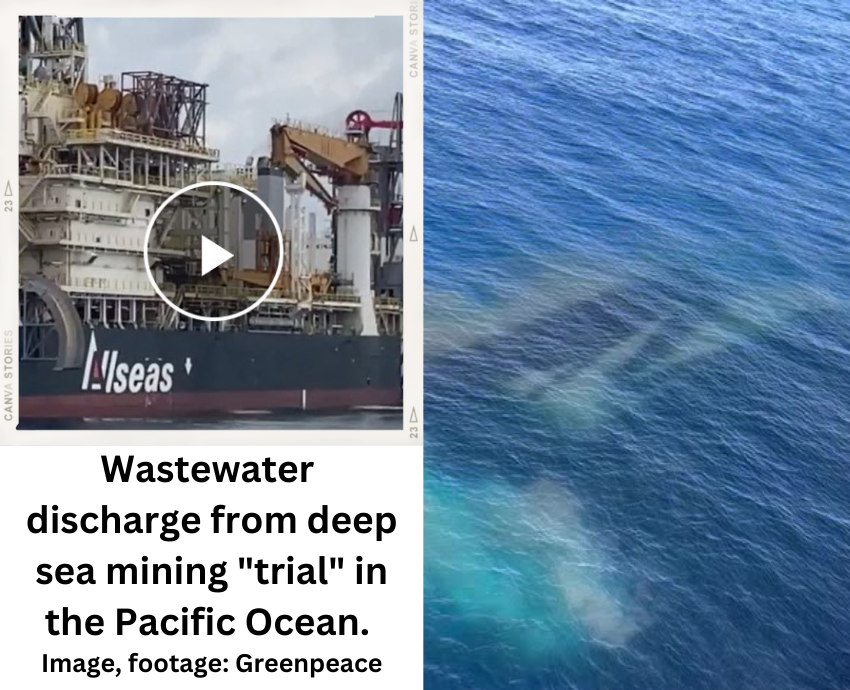

Missing from TMC’s slick video hailing the success of the project is the pollution from mining activities. Undercover videos obtained by Greenpeace, released in a joint statement with Deep Sea Mining Campaign and MiningWatch Canada on January 10, show wastewater being discharged from the ship Hidden Gem directly into the ocean.

The wastewater contains mercury and lead, which are toxic to many organisms. Sediment plumes from the mining process can spread for hundreds of kilometres, blanketing ecosystems and clogging the gills of sea animals.

Noise pollution from deep-sea mining is estimated to travel for more than 500 kilometres, which disrupts the migration patterns of animals sensitive to sound, such as whales.

Mining activities such as these could indirectly accelerate global warming by killing underwater organisms responsible for sequestering large amounts of carbon dioxide.

Louisa Casson, from Greenpeace’s Stop Deep Sea Mining campaign, said that TMC has shown “a blatant disregard for the environment and to people around the world who depend on healthy oceans”.

“The exposure of this incident and scientists’ criticism of the companies’ approach provide yet more reasons why deep sea mining should not be allowed to start on a commercial scale,” Casson said.

TMC aims to use the data collected from the project to downplay the destructive impacts of deep-sea mining and forge ahead with plans to start large-scale operations next year. However, Deep Sea Mining Campaign, Greenpeace and MiningWatch Canada’s statement said that scientists involved in the project “allege that flaws in the scientific program’s monitoring system, poor sampling practices and equipment failure make the data collected meaningless”.

Despite opposition from Indigenous communities, NGOs, scientists and environmental activists, commercial mining could be permitted from July, even though the ISA has failed to finalise laws regulating the industry.

A New York Times investigation last year revealed how the ISA has been captured by corporate interests — secretary-general Michael Lodge publicly supports deep-sea mining and has criticised scientists for voicing their concerns over the environmental impacts. The ISA approved the trial in September last year, despite its own Legal and Technical Commission having “serious concerns” with the project.

Catherine Coumans, from MiningWatch Canada, said that the ISA “played a significant role in the failures of this latest deep sea mining test and has also failed to publicise the unauthorised dumping of mine waste”.

“This test highlights the ISA’s lack of transparency and credibility as a regulator and the very immediate risks posed by deep sea mining on marine health and biodiversity of the ocean, our global commons,” Coumans said.

Vanuatu, Fiji, Samoa, Micronesia, Palau and Papua New Guinea have called for a moratorium on deep-sea mining. Costa Rica, Chile, Germany, Spain and Panama have called for a “precautionary pause” on deep-sea mining, citing a lack of scientific evidence about the extent of impacts and insufficient environmental regulations.

The French parliament voted on January 17 to ban deep-sea mining in its waters, just months after President Emmanuel Macron called for a complete ban at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in November.